Theater Reviews Page | Previous Theater Review | Next Theater Review

Edgy

Published in The Hopkins Review, Summer 2014, New Series 7.3

The heart wants what the heart wants, as Woody Allen trenchantly puts it. To the marriage of true minds we do not admit impediments, if only because the barriers against such a marriage generally do not hold. Unfortunately, the loins also have wants. They want what they want, and little will change that either. At some level, this is a problem for nearly everyone, because our hearts and our loins so often want different things.

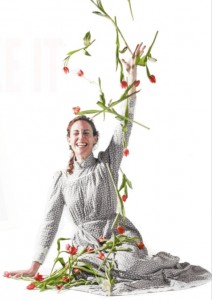

This conflict was fascinatingly illuminated by two brave and iconoclastic works about sex I saw a day apart in the same place, Theatre Row on 42nd Street. One was Intimacy, by Thomas Bradshaw, put on by the New Group; the other was Toni Bentley’s adaptation of her own erotic memoir, The Surrender, a one-woman show with Laura Campbell standing in for Bentley.

The shows are brave for the forthrightness with which they deal with their subject. Sex and sexuality may be ubiquitous in the theater, but extreme honesty about these things is a lot rarer. Even today, for instance, there are usually limits to the depiction of sex onstage. These shows, particularly Intimacy, simply brush almost all limits aside. (Actual erections as part of the performance are, to pick an example, a new one on me – at least on that block of 42nd Street and in this century.)

Feudal Positions

The shows are iconoclastic for the potentially unpopular things they say. One potentially unpopular thing said in The Surrender would be that a (mostly) straight woman loves anal sex. The iconography of the act (male superior, woman not) sorts awkwardly with the feminist ideals most of us like to think we share. Yet if Bentley has one theme, it is that her greatest release occurs precisely when she is most objectified, most, to use her own word, slutty. (“Anal sex is about cooperation. Cooperation in an endeavor of aristocratic politics, involving rigid hierarchies, feudal positions, and monarchist attitudes.”) One could take issue with this analysis by contending Bentley is “topping from the bottom” (in all senses of the word), but this facile formula really fails to do justice to Bentley’s feelings and views.

No, if Bentley is saying anything at all about this contradiction, she is saying that the “sluttiness” (anal and otherwise) she practiced with the lover she called A-Man and with others may not have contradicted so much as ignored all elevated notions of human dignity, and that orgasm trumps theory.

In so postulating, she is not falling into the opposite fallacy, the one championed by deSade and The Story of O, for instance, that there is a mystical significance to the male-superior position. It’s simply that the loins want what the loins want. Bentley may be looking for what she calls “the joy that lies on the other side of convention,” but it is not the unconventionality per se that she craves. Just the joy.

She has another leg up on those Frenchmen, de Sade and Réage, as well. Justine and O have to take place in neverlands, fantasized chateaux where perversity can flourish. Bentley, by contrast, makes her argument out of what she claims is actual experience. It is believable, told with a thousand piquant details conveying the ring of truth, like the gym-rat environment where she meets A-Man (and a redheaded woman who serves for a time as their mutual lover), or the way she encounters a born-again Christian (whose backsliding she prompts) while cutting dowel at a Home Depot.

Universally Availed-Of

The Surrender, then, seems dedicated throughout to honesty about sexual reality. Intimacy at least starts out the same way. This seven-character play, built around the ubiquity of masturbation, pornography, and the sexual fantasies that fuel them, is like Schnitzler’s La Ronde, depicting a circle of tangentially-associated individuals whose sexual secrets end up linking them together in unacknowledged ways. The play takes for granted, as did Kinsey, that masturbation is pretty much a universal behavior, at least for men, and that pornography, the ultimate masturbatory aid, being universally available to all on the Internet, is therefore pretty much universally availed-of. Further, playwright Thomas Bradshaw assumes that the fantasies catered to by pornography are those its consumers resort to because what they crave is not available to them in real life.

Act One is largely devoted to exploring this phenomenon: the disconnect between what we want and what we get. For instance, the (mostly) straight Hispanic contractor Fred (David Anzuelo) has a thing for boys and has the thong underwear to prove it; both widowed father Jerry (Keith Randolph Smith) and teenaged son Matthew (Austin Cauldwell) spend time and energy lusting after the 18-year-old sexpot Janet next door (Ella Dershowitz). The difference between what these men want and what they can get (or at least what they think they can get) is papered over with vast amounts of hypocrisy. And Act One is largely devoted to stripping away the hypocrisy, depicting copious acts of porn-watching and masturbation.

Act Two is something else. Act Two might be subtitled “But if you try sometimes, you just might find, you get what you want after all.” The conceit is that Matthew, on the cusp of high school graduation, is given a high-end movie camera and the money to make a movie, and decides to become an auteur of porn, casting all of the members of this daisy-chain of secret suppressed desires, who are all persuaded to abandon shame and do for the camera what they so badly wish to do in their personal sex lives.

Casting Off Pudor

And this is where the two plays part company. Bentley is at least presenting her anal exploits as autobiography. She really did get to do what so overwhelmingly appealed to her. (If it didn’t happen, it is presented with so much emotional verisimilitude that you coulda fooled me — and probably everyone else in the audience.) But it’s one thing for a single person to overcome her inhibitions, her hang-ups, her what-the-ancient-Romans-summed-up-with-the-word-pudor (from which we get “pudenda” among other words) meaning, non-judgmentally, a sense that some things are appropriately covered up and private. It’s another for a whole diverse circle, as in Bradshaw’s play, to cast pudor aside.

Bradshaw unrolls this casting aside process starting with Janet, the 18-year-old, who turns out to be an actual porn star featured in Barely Legal, unashamedly catering to the very sort of fantasy her neighbors had been entertaining about her. From her perspective, nothing could be better than triggering such desire and occasioning such happiness. I wonder whether many porn stars feel like this, but I have even less confidence that the shedding of inhibitions on the part of the other characters would go as smoothly. The conclusion of the play is meant to carry somewhat the same emotional resonance as the conclusion of a Shakespeare comedy that ends with a brace of weddings, only here (with one completely unbelievable exception) the couplings are literally that only, not actual marriages. Instead we get two instances of ephebophilia, one of analingus with overtones of incest, and a great deal of frottage. After the frequently savage comedy of the first act, this all seems a bit discordant, as if someone had waved a magic wand or rolled out a deus ex machina. And in fact that’s almost precisely what this mass-deliverance from shame is.

For the fact is, most of us don’t lose our pudor. It’s hard-wired into us, and whether this hard-wiring is a good thing or a bad one is a serious question deserving a more thoughtful answer, not a cheaply feel-good ending. What would really happen if people lived out in real life the scenarios that roll through their heads while their hands are busy with those pudenda? A lot would have to be rearranged in their lives, that much is certain. It’s quite arguable that without pudor our lives would be unlivable. But even if that were not true, there are questions about morality. Arguably there are things people want which it would be wrong for them to have (and maybe even to want). Where that line gets drawn would be a matter of near-total disagreement in almost any demographic, but the notion that we should all be trying to live the dream, whatever the dream might be, is clearly wrong, and almost everyone would agree it’s wrong. Some dreams are dangerous and should stay firmly ensconced in fantasy. Maybe most of them.

Not Blinking

No such easy resolution in The Surrender. Granted, the anal penetration Bentley so prizes at the hands or more accurately the penis of the lover she calls A-Man does her no medical or emotional harm. Not the act itself. But it both restricts and frees her in unsustainable ways. It will hardly be surprising that the relationship consists exclusively of sex: no dating. As she puts it: “We’ve never been to a movie and don’t plan on going to one, ever. Why would we? We are the movie…” So the profound sex paradoxically makes the relationship shallow and hence vulnerable. Nor will it be surprising that the “butt-fucking,” to use her own repeatedly applied term for it, is part and parcel of a boundary-free association with A-Man in which both of them have liaisons with others as well, a life of libertinage in the technical sense. (“If a man can possess a woman sexually – really possess – he won’t need to control her … other lovers.”)

To maintain equilibrium in a relationship like that requires a studied inattention to one’s lover’s other attachments. That can be costly enough from an emotional standpoint when one is as thoroughly in love with one’s partner as Bentley obviously was with A-Man. But even if it is a cost one is personally willing to pay, it is impossible to find a ready supply of counterparties, other lovers of the same man who will also be willing to share. And the play, to its credit, does not blink when the story reaches that point.

A-Man is a gym rat, brought into Bentley’s life as part of a threesome with another woman who frequents the gym. But though that other woman drops out of the picture, A-Man takes another lover from the same gym, a “mousy blonde” (in the show, though a brunette in the book). When the two women become aware of each other, it cannot and does not end well. I quote the climactic scene from the book, which is liberally quoted in the script: “I asked her if she loved A-Man. I hadn’t planned on asking, but I guess I wanted to know… Her big … eyes filled with tears and she murmured, ‘I try not to.’” And after that, the only course open to Bentley is renunciation. And in the script, she claims to have cried every day for months.

No Support for the Local Libertine

The cost of Bentley’s unspeakably thrilling erotic freedom, then, is a thoroughly broken heart, actually two of them (the mousy blonde/brunette being similarly afflicted). Even had there not been the operatic break, the thrill would have diminished. Even Bentley acknowledges that constant sexual encounters with the same person are apt to diminish in power, as the parties become desensitized to each other; as she puts it in the book: “With time, cracks appear in the walls of the Garden—and reality, insipid reality, slithers in with its insidious poison.” That is the way of it; desensitization will affect most sexual and most emotional relationships over time. The prevalence of long-term marriages, still, even in this day and age of divorce and late marriage, strongly suggests how acceptable this desensitization is to a wide variety of us. The thrill always fades to a great extent, and most of us can deal. But, one suspects, never Bentley nor A-Man.

Tears for months or not, she continues to have lovers. But it’s clear her heart isn’t in it. More importantly (in the play at least), her ass is not in it; she does not engage in her favored activity with any lover after A-Man. No wonder; in the real world there are too many of “mousy blondes” and too few libertines.

A libertine might draw from the scarcity of peers the moral that the world is just not full enough of men and women brave enough to follow their loins, whereas if there were more brave people ready to ignore their pudor, we’d all be happier. This perspective may even be correct. But most of us don’t aspire to a level of erotic fulfillment that commandeers our lives, as Bentley’s commitment has apparently done. Bentley’s example suggests it would be more likely to imperil our happiness than to enhance it.

Mickey, Judy and Gerard

Most people have the opposite problem, the problem confronted in Intimacy. The loins may want what the loins may want, but there are a lot of other parts of the body and the spirit going a different way. We want company, we want children and families, and communities – communities that we would threaten if we pursued our sexual hearts’ desires too vigorously.

It is surely in the uneasy clash between these competing pulls that pornography is born. Pornography is an attempt to square the circle, to reconcile the unreconcilable. Of course it leads to the conflicts and the hypocrisy so clearly limned by Act One of Intimacy. Desire and pudor are locked in a battle neither can win.

In Act Two, when the youngsters involve their elders in their Mickey Rooney-and-Judy Garland let’s-make-a-movie moment, it rapidly becomes an indigestible Gerard Damiano moment. Young auteur Matthew praises old auteur Damiano (who created the unspeakably bad Deep Throat) as featuring real scripts and real acting. If a character admires Damiano for that, something is clearly amiss with that character’s sensibilities, and, however charming we may find his desire to film an hommage, we are not going to drink the same Kool-Aid ourselves. The direction by Scott Elliott neatly distinguishes the characters who know they don’t know how to act – and hence approach their roles using their own voices if not their own words – from the characters who ostensibly know how to act and so put on different voices. But it’s wasted, because the most convincing of these supposedly on-camera performances still sounds stilted and unnatural – as did those of Linda Lovelace and Harry Reems, whose example is actually played for us on a video monitor during the proceedings (lest we forget). If acting in a porno movie is actually going to liberate you, it should not first make you inane. Or so one would think.

Yes, one can say, apparently along with the playwright and the director, that this is all meant to be lighthearted, and that the notion of everyone getting over their hang-ups while getting it on in a daffy, unwatchable hommage to something that needs no tributes is charming. And I guess it is, but the savagery that made Act One so delightfully edgy is leaking out of the play like air from a damaged balloon.

A Sliver of Epic in a Tent

Of course one doesn’t have to talk about sex to be edgy, even in seen-it-all New York. There has been a lot of comment about Natasha, Pierre and the Great Comet of 1812, being presented in a space on West 54th Street called Kazino. In fact, it might well be that much of the buzz results from it being presented in that space, a tent. It is set up like a cabaret, with actual bar service at the tables, and the action taking place all around the audience: at both ends of the tent, along all the walls, and in the corridor separating the tables. Even the band is dispersed a bit around the space. And David Abeles, the actor who sings Pierre, also participates with the band. Naturally such things, or things quite like them, have each been done before, but perhaps not together in the very purlieus of Broadway. (The show moved to Kazino from a venue in the Meatpacking District.) Still, this staging has a bracing novelty to it.

The tale, as the title suggests, is drawn from some incidents at the end of Book Two of War and Peace. It quite fills up the two hours with only a sliver of the huge novel. In my estimation, it should be categorized as an opera rather than a musical, though I would be the first to acknowledge that there is no bright line separating the genres. But the traits that drive my categorization of the show are: a near-complete consignment of oral communication to song, a complete disdain for rhyme in the lyrics, and what one might call an operatic attitude (fervent emotion largely expressed through the music) for want of a better word. That said, opera is usually presented with orchestras rather than bands, even bands which, with the exception of some synthesizers, are all classical instruments (cellos, drums, viola, clarinet, bass, piano and oboe). As in Spring Awakening of a few seasons back, a classical musical palette is placed at the service of modern rhythms and melodies, although fittingly there is a strong influence of Russian music here. But where Spring Awakening’s music was often infused with rock influences and had been parceled out into discrete songs, here composer/lyricist Dave Malloy’s score is all contemporary classical music, and while it is presented in definite units, the word songs does not come readily to mind. The program speaks of “musical numbers,” but few members of the audience will go out humming them. Whatever one calls the music, fortunately, it is propulsive, powerful, and creates the feeling of a fevered dream.

A Conventional New Life

It is subtly surprising that all this innovation or near-innovation is placed at the service of a conventional tale. Tolstoy’s initial critics may have seen the huge, ungainly book as scandalously ungenred, and certainly there are things in the book like bastardy and abortion, philosophizing about the genesis of historical events, and battle reconstruction, few of which have seldom been the stuff of conventional romance. But the sliver of the story under consideration has more of what one might call the usual stuff, structured around a threat to a beautiful young woman’s premarital chastity and to her affections, set against a background of high society in a time of war. There is a ball and a duel and a visit to the opera. We are in a completely different universe from that occupied by the two plays discussed earlier; here it is meaningful to speak of a woman being “ruined.” And the catharsis at the end is symbolized by the appearance of a comet. (I am not sure why Malloy changed its year; it actually appeared in 1811.) But – in a fashion similar to the “purple summer” phenomena evoked at the conclusion of Spring Awakening – it is transmuted into a cause for hope. Here Pierre describes it:

The comet said to portend

Untold horrors

And the end of the world

But for me

The comet brings no fear

No, I gaze joyfully

And the bright star

Having traced its parabola

With inexpressible speed

Through immeasurable space

Seems suddenly

To have stopped

Like an arrow piercing the earth

Stopped for me

It seems to me

That this comet

Feels me

Feels my softened and uplifted soul

And my newly melted heart

Now blossoming

Into a new life

This is conventional; Pierre’s “new life” may be a number of things, but primarily it is the first moment of his love for Natasha, which will culminate in their marriage many hundreds of pages hence, long after the action of this show. (As far as the show goes, the comet is the conclusion.) There is edginess here, but it resides in the overall presentation – and in what follows immediately upon these words: a spine-tingling discordant but beautiful upward chromatic slide of screeching synthesizer notes (not unlike that of the strings at the end of A Day in the Life) combined with a lighting effect that conveys the sense of a comet passing directly overhead.

Seriously Gilt

And there’s one place you can always look for edginess: the subgenre known as the theater piece. The exact boundaries of this subgenre are open to debate, but certainly such things as unconventional or absent plotting, audience participation, performer abdication of role-playing, and severe generic mashups are hallmarks. To one degree or another, all were to be seen in the Rude Mechs’ production Stop Hitting Yourself, recently on display at the Claire Tow Theater at Lincoln Center. The Rude Mechs (their name a tip of the hat to Midsummer Night’s Dream), are a theater troupe out of Austin, Texas, from whence they send emissaries on the road with shows they have created as a collective.

Theater pieces may have a fringe-y and hence low-rent reputation, but there was nothing low-rent about this performance, starting with the set, a large collection of objects, all gilt, including (but not limited to) 17 chandeliers, a mirrored set of steps that doubled as a queso fountain, a huge illuminated dollar sign, a large-than-life male nude statue, a suit of armor, a grand piano, and heaps of treasure, including gilded athletic shoes. Clearly we are in the realm of some kind of abstract fantasy of wealth, a place where, as Bob Dylan once put it, “Money doesn’t talk, it swears.” Lying in the foreground as the audience files in is a half-nude bearded man with matted hair, his body smeared with a yellow substance we will later discover to be congealed queso. Asleep? Dead? We learn by the end of the action, all of which turns out to be a flashback leading to this point.

Obviously, a character who looks this way is the one of those things that is not like all the others. What is Wildman (Thomas Graves), a rude creature of the forest, doing in this environment of epicurean wealth and splendor, one that looks as if Margaret Dumont could emerge at any moment to preside over it? And how will he fare within it? Those questions are answered, sort of, in the proceedings that follow.

More Brecht Than Rand

The program notes say the company was meditating on the ideas of Ayn Rand while creating the piece, and perhaps so, but what I saw was more a parable about the divide between the 1% and the 99%, a current and perennial issue in our wealth-dominated polity and culture. Rand at least theoretically believed in a form of individualism which, while liberated from notions of altruism, also was not actively hostile to the have-nots. This piece seems to be largely about just such hostility. In consequence, I at least saw more Brecht here than Rand.

Wildman arrives at this place, which turns out to be the palace of the Queen (Paul Soileau), in the run-up to an annual charity ball at which characters compete for a royal favor. Wildman is willing to put on rich people’s clothes and try to try to learn some plutocratic manners, in order to compete for a favor which would benefit the threatened natural environment, the wild from which he comes. But in so doing, he is running directly contrary to the ethos of thoughtless consumption and aggressive self-seeking by which the denizens of the palace live. That resistance is personified in the Unknown Prince (Joey Hood), a shady character who just wants to be made rich enough to become accustomed to the style of the people who regularly feature on the palace’s guest list.

Along the way to the charity ball, the audience will see various things that do not usually appear in plays: a weird kind of ballroom dancing somewhere in between clog dancing and tap, breaks in which the audience is requested to close its eyes for a seven-count in order for the cast to move from one absurd tableau to an unexpected different one, a kind of quiz show in which members of the audience are invited to compete for $20 bills by doing silly or embarrassing things, and moments in which members of the cast apparently tell snippets of their personal history (a la the dancers in A Chorus Line). The thematic and didactic thread seems to break at certain points in the performance, as one might expect. But it is fun.

The overall effect, therefore, is a bit like the one Rachel Maddow produces when she recounts horrifying, angering events in her patented droll, chipper manner. One is amused by the comic delivery at the same time as one is suitably appalled by that which is delivered. But an entertaining manner of explication risks being too far out of keeping with the subject, even distracting. Bread and circuses are fun, of course, but they are offered to us to keep us from thinking of other things. When the performance is itself a circus of a sort, quite literally a variety show with audience participation, we may be in danger of missing the emotional point. Even when we take in, intellectually, that wealth breeds misrule of society and of the environment, we may be having so much fun we do not take the point in emotionally. And that would be too bad. Of course, that itself might be the real point. Hard to tell with a show like this.

Here’s to Edgy

There is pleasure in seeing old classics done well, and pleasure in big, comfortable shows, and pleasure too in seeing well-known stars. But the shows discussed here remind us how vital it is that the theater keep on giving us things we haven’t seen before, might not be comfortable watching, things that stun us and surprise us. I would go so far as to say that if theater ever stops giving us edgy work, it will cease to be theater. Here’s to edgy.

Copyright (c) Jack L. B. Gohn

Theater Reviews Page | Previous Theater Review | Next Theater Review