At the Apex

Theme Songs Page | Previous Theme Song | Next Theme Song

At the Apex

Dockland, Music by Darryl Runswick, Lyrics by Lee Crabbe, Sung by If (1970), Encountered 1974

Buy it here | See it here | Lyrics here

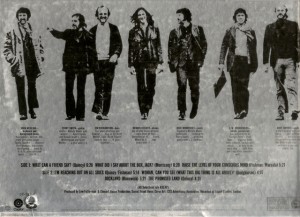

I tend to acquire new interests at the same time as everyone else, but I seldom abandon them when the memo goes out to move on. Case in point: as the 70s progressed and people stopped thinking of Chicago or Blood, Sweat & Tears as cutting-edge, I just doubled down on jazz-oriented rock groups (or was it rock-oriented jazz groups?) by following bands with forgotten names like If, Dreams, and The Flock. If was a group I particularly liked: a British septet with two reedmen atop a standard rock band foursome fronted by a tenor vocalist named J.W. Hodginkson.

Working Class World

I must have picked up If’s eponymous debut album in a remainder rack. I still have the LP, clad in a silvery reflective jacket, punched in one corner: the telltale mark of a remaindered record. No surprise it was remaindered: despite coming out on a major U.S. label, If obviously was not meant for great things in the overheated U.S. record market of that era. It was too foreign, too jazzy, its members equipped with insufficiently big hair for the 70s (two of them are perceptibly balding on the jacket photos). But they came into my life at an opportune time for me, because I was attempting a self-taught crash course in up-to-date working-class-world British culture. If, and especially its song Dockland, were playing a lot throughout the process.

Offenses Against Decorum

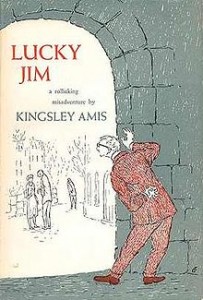

The crash course was necessitated by the decision I’d made around the same time I bought the album to do a dissertation on Kingsley Amis, the British novelist and poet. I’ve mentioned this at various other spots in these pages.[1] I wanted to do a dissertation on someone I could actually talk to; I was sick of the inability to ask questions.[2] More than anything else, though, and more than even I recognized at the time, my dissertation choice was a declaration of independence from the Hopkins English Department. Educated people everywhere had guffawed their way through Amis’ freshman effort, Lucky Jim (1954), of course, but it was light humor, my dear, not Joyce or Nabokov, and it was, after all, a sendup of academia, and we do have to be careful not to be too disrespectful. Amis’ offenses against decorum had then multiplied: bedroom farces, a pastiche murder mystery and a pastiche ghost story, science fiction criticism and anthologizing, a book on James Bond, an actual James Bond sequel, jazz criticism, a column about drinks, television scripts, and a drift to the right politically. To be sure, the man had his respectable lit-crit side as well, but in choosing Amis to write about I knew I was detouring from the approved path of giving serious attention to serious writers working in serious genres.

The crash course was necessitated by the decision I’d made around the same time I bought the album to do a dissertation on Kingsley Amis, the British novelist and poet. I’ve mentioned this at various other spots in these pages.[1] I wanted to do a dissertation on someone I could actually talk to; I was sick of the inability to ask questions.[2] More than anything else, though, and more than even I recognized at the time, my dissertation choice was a declaration of independence from the Hopkins English Department. Educated people everywhere had guffawed their way through Amis’ freshman effort, Lucky Jim (1954), of course, but it was light humor, my dear, not Joyce or Nabokov, and it was, after all, a sendup of academia, and we do have to be careful not to be too disrespectful. Amis’ offenses against decorum had then multiplied: bedroom farces, a pastiche murder mystery and a pastiche ghost story, science fiction criticism and anthologizing, a book on James Bond, an actual James Bond sequel, jazz criticism, a column about drinks, television scripts, and a drift to the right politically. To be sure, the man had his respectable lit-crit side as well, but in choosing Amis to write about I knew I was detouring from the approved path of giving serious attention to serious writers working in serious genres.

All that messing in popular genres did not mean Amis (born 1922) was exactly contemporary from that era’s vantagepoint. Contemporary would have been Swinging London. One of Amis’s novels, Girl, 20, explicitly dealt with that scene. But it was an acidulous and huffy approach, focusing primarily on an older character, a conductor who could be great but throws away his talent in a ridiculous effort to fit in with London’s gilded youngsters. Amis clearly was not going to be buying his duds on Carnaby Street.

Rock and Jazz

The music of If wasn’t a perfect match for either the times or my dissertation topic, but a significant step in that direction. Swinging London was rock, not jazz, and If was jazz as much as rock, and its members a bit long in the tooth to be fabulous in that era’s eyes. [3] That said, its musicians were and certainly felt more contemporary than the jazz Amis had written about for The Observer in the 1950s (and I’d photocopied and read through for my dissertation).[4] Read the liner notes of the album, and you get a sense you’re being served up a compleat blending of up-to-date rock and up-to-date jazz.

(To read the blurbs, click here: If Jacket Detail.)

Big Brick Walls

But that was okay. On the page, Amis sounded and felt like a product of the big brick walls of industrial Britain, the world of I’m All Right Jack. Lucky Jim plays a practical joke on Johns, his dim colleague, writing a threatening letter as if it came from an irate workingman:

This is just a freindly letter and I am not threatenning you, but you just do as I say else me and some of my palls from the Works will be up your way and we sha’nt be coming along just to say How do you can bet.

Don’t these Works sound as if they come from the same factory neighborhoods you see in the background in A Hard Day’s Night? Or, more to the point, don’t they sound like the neighborhood conjured up in the lyrics of Dockland?

It’s a dockland scene Where the water runs There’s a big lock gate And it runs in tons While the big ships wait While the water runs… There’s a factory wall Where the flour-bags lie And they’re stacked so tall That they reach the sky By the factory wallTo be technical about it, these are all different places. Lucky Jim takes place at a provincial British university, reportedly based in part on the University of Leicester in the British Midlands, in an area where “the Works” were indeed to be found;[5] A Hard Day’s Night was mainly shot in London;[6] and Lee Crabbe’s lyrics, quoted above, describe a canal and docklands in Ipswich, Suffolk,[7] on England’s east coast. But the slightly drab, slightly run-down world still pulsing with industrial life was common to them all.[8]

A Visit With the Great Man

So I felt that by playing this record and humming the melody, I was truly helping myself (in a small way at least) to get ready to tackle my subject. My other preparations, in addition to mounting a determined effort to lay my hands on everything Amis wrote or which had been written about him, consisted of writing the man himself, and asking if I could interview him.

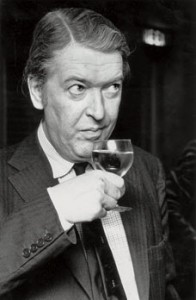

The answer I got back was both cordial and noncommittal. He “might buy [me] a drink.” Armed with little more than that level of commitment on Amis’ part, I got myself and S. to London in July 1974. Amis and I agreed to meet on the 16th, at the Garrick Club, I believe in the very room pictured here. [9] I think he wanted to look me over, to decide if I was the sort to whom he wished to extend his help. Originally he told me he would have to leave at around one. However, as I was apparently making the right impression, he then invited me to come along with him to what I later learned was a fixture in his life at the time, a Tuesday lunch gathering with various conservatively-minded writers at Bertorelli’s, an Italian restaurant.[10] The day I was there, I met John Braine, author of Room at the Top, the movie of which I’d seen (and I’d also read the book), and Sovietologist and Amis co-author Robert Conquest.

[9] I think he wanted to look me over, to decide if I was the sort to whom he wished to extend his help. Originally he told me he would have to leave at around one. However, as I was apparently making the right impression, he then invited me to come along with him to what I later learned was a fixture in his life at the time, a Tuesday lunch gathering with various conservatively-minded writers at Bertorelli’s, an Italian restaurant.[10] The day I was there, I met John Braine, author of Room at the Top, the movie of which I’d seen (and I’d also read the book), and Sovietologist and Amis co-author Robert Conquest.

I was very impressed, though none of these people was what I had expected. I might have articulated it differently to myself at the time, but it was as if the entire left-wing British intelligentsia had turned right. (No solidarity with “palls from the Works,” and no romanticizing “flour bags … by the factory wall” or “big lock gates.”)

At the conclusion of the lunch, Amis and I made arrangements for me to come up to his suburban home in High Barnet and do an extended interview, which occurred on July 24. This is not the place to go into the specifics of my visit to his home or our conversation, much of which turned up in my dissertation. All I need report is that Amis was a delightful host, that I met Amis’ formidable then-wife, the novelist Elizabeth Jane Howard, and that I got back on the Tube sated in body and mind.

This generous helping of rubbing elbows with literati was supplemented by my going to Bloomsbury and actually doing some research at the British Museum.

And a Not-So-Great One

And I also had one other literary adventure on this trip. I’ve mentioned earlier in these pages that I had also written a book-length edition of some Romantic-era poetry, even before I had gotten going on the Amis project. This had led to the discovery that there was something of a fight going on over a new standard edition of one of those poets. There was a Big Name Professor in America and a Big Name Professor in England on opposite sides. In the course of a year or so, I would meet the American. But while in the U.K., I had an exceedingly odd dinner with the Briton. I think he was going senile or mad or both, but he was still in the game at that point, and trying to recruit me for his faction. This, despite my making it plain that with my newfound focus on contemporary literature, I was somewhat hors de combat when it came to the Romantic poet in question. I don’t think my disclaimers made the least impression on him. Nor was literary factionalism all he was trying to recruit me for; despite his denunciations of certain academic rivals as “bum-boys,” I could sense a definite disappointment when I mentioned that I was traveling with my wife, and even more when I made it plain that I was headed back to her immediately after my strictly business get-together with him.[11]

It was thrilling to be among these people of literary achievement, and it was a heady thought that I might one day be their equal. (I certainly aspired to be as accomplished and celebrated as Amis and as Big a Professorial Name as my host the editor.) Of course, it was not going to happen, but I didn’t know that then. It’s fair to say that, because my anticipated glowing writing career misfired so badly, this couple of weeks turned out to have been the apex of my literary life, both for whom I was associating with and for what I was doing.

And I and S. were playing tourist all the while, too. In among these literary activities, S. and I traveled all over England, courtesy of our Britrail Passes: Cornwall, Cambridge, and Edinburgh, Greenwich, York and generous helpings of London.

Just a Great Song

During all those travels, I continued from time to time to think of that Dockland song. It is a wondrous thing, because the melody, chords, and lyrics are so tightly integrated, and they all tell the same tale in the same way: that there is a lustrous beauty and consolation (“when I’m feeling down”) in these industrial landscapes, similar to what Wordsworth would have found in a natural scene:

See, the harbor lights are winking far and wide Hear the water lapping at the old keyside See, where the oily swans are breeding There’s a morning tide receding Leaving all the scrapmetal clean It’s a dockland sceneIn the first two lines, the melody moves downward in a minor chordal progression to the second “See,” sung at the deliciously wrong E directly above the Eb which is the key,[12] and when the lyrics turn to the “oily swans breeding,” and it resolves down to the Eb, there’s a burst of rightness that mirrors the quiet, inexplicable consolation the song is all about. When the lyrics mention someone sounding a ship horn, the band’s horns not only capture the pitches of a ship horn, but the sonority, and the whole strange gamut of feelings hearing one can evoke. Throughout, the song is full of strange, jazzy, exciting chords that underline the unexpected wonder of the harbor view.

Unexpected like my encounter with literary London in 1974.

As Wordsworth wrote in a very different context: “Bliss was it in that dawn to be alive.”[13] I was not going to feel that kind of bliss as a literary man ever again. But I would never forget it.

[2] I was also sick of the Deconstructionist notion that an author could speak with no particular authority about his/her text. I never believed that my teachers really believed this, because they kept slipping bits of an author’s biography into their disquisitions, and why the biography should mean something if the text were so darned autonomous is a question I never heard an answer to. Well, hell, there was no answer. When it came to doing a dissertation, however, I felt like Aristotle, or Roger Bacon, or whoever it really was who wanted to settle the philosophical question how many teeth a horse had by marching over to the stable and counting.

[3] J.W. Hodginson, the lead singer, born in 1949 like me, was the only Boomer.

[4] See my book Kingsley Amis: A Checklist at 25-36 (1976).

[5] The 1972 Webster’s New Geographical Dictionary’s entry on Leicester, at 658, describes the town in part as “railroad junction; hosiery, knitwear, footwear.”

[6] See the detailed rundown of where the movie was filmed in entries in http://www.beatlesbible.com/history/ for March and April 1964.

[7] E-mail from Darryl Runswick, composer, November 6, 2012.

[8] Times change. The University of Leicester and the Ipswich docklands are now gleaming bits of modernity, to judge from photos posted on Yahoo. The places where A Hard Day’s Night was filmed are mostly gone, except for the train stations. (Twickenham Film Studios, where the bulk of it was filmed, has closed and is set to be demolished.)

[9] Source: http://www.garrickclub.co.uk/.

[10] Amis’ biographer, Zachary Leader, references the:

Weekly ‘fascist’ lunches at Bertorelli’s restaurant in Charlotte Street. These lunches, held first on Thursdays, then on Tuesdays, seem initially to have been an outgrown of the lunching arrangements Amis made with London friends on his weekly visits from Cambridge. Bertorelli’s was cheap, conveniently located near the Spectator offices, and arge enough not to book ahead. It served unpretentious Ango-Italian food unpretentiously… The fascist label was coined by the lunchers themselves.

Leader quotes Amis’ son Martin: “Both Kingsley and Bob [Robert Conquest], in the 1960s, were frequently referred to as ‘fascists’ in the general political debate. The accusation was only semi-serious.” Leader continues:

[H]ere they would chat and carouse with other fascists, among them the journalist Bernard Levin, the novelists Anthony Powell and John Braine …, and the defector historian Tibor Szamuely. Other regular participants included Anthony Hartley of the Spectator, D.C. Watt, the historian and political scientist, Russell Lewis, Director of the Conservative Political Centre … and the American Journalist Cy Friedin.

Z. Leader, The Life of Kingsley Amis at 565 (2006). Bertorelli’s is now a chain, and not highly esteemed by its Web reviewers, not even the Charlotte Street branch, at least as I gather based on this link, as accessed November 18, 2012. But filled with literary men of achievement (I don’t think there were any women present) it was very impressive that 1974 day.

[11] I always felt sorry for him, so obviously in decline, and so clearly marked out to lose the fight over his edition of the poet, which ran to one more volume the next year and then was stopped by the university press that had been publishing it. The American Big Name not only was part of the group that had a stop put to the older man’s edition, but has since been bringing out his own.

[12] In the wonderful original recording sung by the composer, Darryl Runswick, audible here, the key is C, and the tension-causing “See” is a Db.

[13] William Wordsworth, French Revolution (1805).

Copyright (c) Jack L. B. Gohn, except for all images other than the last