House of Song and Laughter

Theme Songs Page | Previous Theme Song | Next Theme Song

House of Song and Laughter

Come Together, by John Lennon & Paul McCartney, performed by the Beatles (1969), encountered 1969

Buy it here | See it here[1] | Lyrics here | Sheet music here

Beginnings, by Robert Lamm, performed by Chicago Transit Authority (1969), encountered 1969

Buy it here | See it here | Lyrics here | Sheet music here

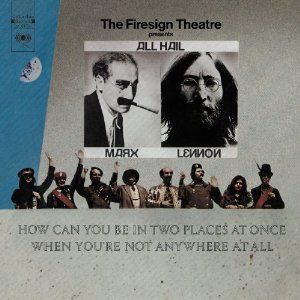

How Can You Be In Two Places At Once When You’re Not Anywhere At All by The Firesign Theatre (1969), encountered 1969

“Time passes much too quickly, when we’re together laughing…” Robert Lamm, Beginnings (1969)2209 Rittenhouse Square in Philadelphia, where I lived during my junior and senior years of college, occupied a deceptively grand-sounding address (it isn’t actually on Philly’s famed Rittenhouse Square), but it certainly proved grand enough for me and my housemates. There were officially three of us – no, wait, there were officially two of us, one of whom wasn’t actually one of us at all unofficially – but in reality there were four of us if there weren’t five – unofficially. It was that confusing (as college housemate arrangements so often are).

Perfect for Us

Somehow it had been agreed toward the end of my sophomore year that I and my girlfriend S. and two of her freshman friends from Baltimore, Otts and Chuckie, would all figure out a way to room together. We had all done the campus thing, and were eager for the excitement of downtown. But where? We were wandering around a side street downtown with eyes peeled for “For Rent” signs when a door opened and a hippie-ish art student type came out, and we accosted her, as someone who looked a likely bet to share both our outlook and our limited finances. She chatted with us for a while, then offered to show us her house, shared with some other art students, as an example of what we might find.

It was perfectly sized: three bedrooms, two with bath, two with studies. And it had atmosphere to burn: erratic but carefully drawn stripes running along floors up walls and on the ceiling, a highly unconventional color scheme, and, in one room, a mural of a harpy-like monster to which the residents had added a sculpted torso that came out of the wall at you. Naturally, we didn’t want to live in a place like 2209; we wanted to live at 2209. Was there any chance this place would be coming available? we asked. Why, yes, as it turned out, there was. The caravan of artists was about to pull out. We formed an instant determination to succeed them.

A Little Fraud Among Friends

We were warned that the rental agent, a man with the unlikely name of George Wallace, was devoted to enforcing the mandate of the landlord, a man with the unlikely name of John L. Sullivan, not to rent to groups of college kids. We needed a married couple as a front. S. was the only young woman in our circle, so she had to be the fiancée — and she was going to be in Philly the summer of ’69 to spearhead the negotiations, but all of the guys destined to be the actual rent-payers were going to be out of town for the summer. A Philly-dwelling fiancé had to be located. By dint of extraordinary luck, we prevailed upon an otherwise sensible pre-med colleague of mine named Tom who was willing to complete the charade and put his name on the lease. Of course Tom insisted (as did George Wallace) that a bona fide responsible adult put his name on the lease, and so my poor father stepped up with a guarantee; I think he was supposed to be Tom’s step-dad. Could George and John possibly not have seen through this? If they didn’t, they were idiots. And if they did, why bother and not just rent out in the open to the college boys who after all were going to be the rent-paying tenants? Not our problem: Tom (who never set foot in the house, so far as I know) and S., who barely knew Tom, were the happy engaged couple, and my father, who never met Tom, was Tom’s father – and the proprieties were preserved.

I’m glad to say that neither my dad nor Tom ever lost a penny by this rickety arrangement. But it was a harbinger of the generally lawless lifestyle we were to pursue at 2209. We started with that fraud (though we meant and did no harm to anyone by it), and went on from there. It wasn’t just that we were drinking underage or having sex without benefit of clergy. Kids, don’t try this in your home: LSD was literally kept in the fridge for consumption by – one or more of us – but let me hasten to say it wasn’t me.[2] I was one year older than pretty much everyone else who passed through our door, and held down the role of the grownup persona, and that abstemiousness was in keeping with the role. But I had no problems with anyone else’s bliss. It was the Sixties still, even if Nixon had won. And I may have been the designated grownup, but I was a Sixties grownup.

The four or five of us grew quite close, even vacationing together. I can remember borrowing my dad’s Saab station wagon in New York and taking the whole crew together with someone’s girlfriend from Barnard up to the mountains.

Domesticity

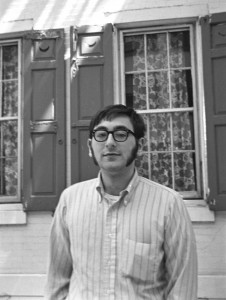

We may not have been art students like our predecessors in phony leasehold, but we did expand on their period style. We found some red carpet and some green carpet, and covered the stairs in alternating colors. S., who was handy with a sewing machine, ran off curtains with fabric of the era, paisleys and wild hot floral prints and such. You can see some of the tamer curtains behind me in this photo of the house from the front. They were hung by simple rings from wooden dowels, but they covered the windows and gave us the atmosphere we were looking for. The material came from Otts’ dad, who wholesaled paper products, especially psychedelic-style writing pads, many of which were covered with these fabrics. In his line of pads, the fabrics were laminated in plastic squares and held in place with spiral binding. In our windows, the fabrics hung free.

We may not have been art students like our predecessors in phony leasehold, but we did expand on their period style. We found some red carpet and some green carpet, and covered the stairs in alternating colors. S., who was handy with a sewing machine, ran off curtains with fabric of the era, paisleys and wild hot floral prints and such. You can see some of the tamer curtains behind me in this photo of the house from the front. They were hung by simple rings from wooden dowels, but they covered the windows and gave us the atmosphere we were looking for. The material came from Otts’ dad, who wholesaled paper products, especially psychedelic-style writing pads, many of which were covered with these fabrics. In his line of pads, the fabrics were laminated in plastic squares and held in place with spiral binding. In our windows, the fabrics hung free.

I’m sure we pained the neighbors. Rittenhouse Square, even the street bearing that name three blocks from the actual grand Square, was for grownup achievers, not for the likes of us. We knew that full well, and felt looked down on. I recall a moment of pushback, when Chuckie grabbed a ball (I think it was on a sedate Sunday morning) and led us all out onto the street, yelling “Everybody out for volleyball, rich people!” (No one came out to play.)

Which is not to say that the neighbors didn’t actually deal with us pretty well. The couple next door, a dentist who sang opera, and his wife, had a cute French au pair we were close to (though the wife told us firmly no one was to seduce the au pair).[3] Behind us across the alley was a gay alcoholic landscape architect or interior decorator (I can’t remember which) who spent most of the time over my nearly two years in the house arranging and rearranging the bricks in his driveway to some fantastic degree of perfection, but spoiled the effect somewhat by driving home plastered lots of nights in a big station wagon, terror of the narrow alley’s garbage cans. He was truculent when drunk, friendly enough when sober. A New Yorker cartoonist, a reserved family man, had the big house to our east.

The Folks That Come With The House

We attracted an interesting crew. There was Carol, a sweet young lady so in love with us and the house she moved from bedroom to bedroom as time progressed. There was a guy we knew only as The Freak, a true drug casualty, who had had some kind of connection to the departed art students but never figured out they were not in residence any more, and turned up from time to time. He’d come in, harangue whoever was home with tales of how he was playing now in the Rolling Stones (once it was The Doors), serenade us with an air guitar solo while singing tunelessly, and end up pulling various illegal substances out of his bloodstained socks and dosing and/or injecting himself with them. Thus fortified, he’d wander back out on the street. There was our summer substitute roommate, Jodie, who used dill in everything she cooked (I grew to despise dill and her other favored ingredient, internal organs), and who was proud of her mom who had reentered the workforce as “a professional astrologer.”

The Freak wasn’t the only music fan in our environment. You could encounter music all over the house, coming out of the stereo in every bedroom, and sometimes the basement. Probably the first specific memory I have of us all together in the house was of the four of us sitting in my and S.’s bedroom listening to Abbey Road which I had purchased the day or the day after it came out.[4] Someone, I think it may have been Carol, then Otts’ girlfriend who became Chuckie’s girlfriend in due course, and reportedly (after my time in the house), Larry’s girlfriend,[5] came in and tried to say something, and Otts shushed her, saying we were having a religious experience. And he was right. (In honor of which I’ve picked the lead-off number from the album, Come Together, as a Theme Song for this piece.)

Opposite Trajectories

I was first and foremost a Beatles man. As readers of these pages know, my loyalties had been fired in the forges of 1964. Otts may have been more open to the very newest stuff, being a year younger and music editor for 34th Street, the new arts-and-commentary supplement to the Daily Pennsylvanian, our campus newspaper, meaning that he received all the hot new albums as they came out. But even for him this was a religious experience.

At that point, though, it would be fair to say, Otts was a Chicago man. Their awe-inspiring first album, Chicago Transit Authority, had just been issued in April: two big LPs of jazz rock. While I and probably most fans were taken with the brass section, what got Otts was the drumming of Danny Seraphine. And if you listen to just the first number, Introduction, and if you know anything about what rock drumming sounded like back then, you can tell that the tempo changes, the polyrhythms, the very un-rock-like tempos, were all remarkable: disciplined, erudite, mostly from a world more sophisticated than rock. Otts hankered to reproduce that feel. So in short order we had Otts’ drum set assembled in the basement, and frequently the house, and no doubt the neighborhood, would resound with Otts attempting to make like Danny Seraphine. So there was never a question I would also be enthusiastic about Chicago.

Abbey Road was, though we couldn’t know it yet, the end of something, the last artistically successful Beatles album. Let It Be, the chronicle of and testament to their breakdown and breakup, would not be released until the end of the academic year. But Abbey Road itself, evan as one of the Beatles’ successes, was rather labored going. Come Together, for instance, came together mostly on the basis of John’s nonsense poetry, delivered in a distortion of his now heroin-addicted voice. (“Hold you in his armchair, you can feel his disease.”) It feels exhausted; a man as great as Lennon should be doing more than second-hand Dylan, however great a man Dylan is, and however apt the hommage.[6] Meanwhile, Chicago Transit Authority both was and felt like a bolt of new and promising lightning. (Check out the video hyperlinked at the head of this piece to see what I’m talking about.) The Robert Lamm song Beginnings makes that quite explicitly, repeating the phrase “only the beginning” time and again.

It would be a mistake to make too much of this. Every age, every year, every moment, is a transition between something and something. There are so many things out there to wax and wane, that you can always pair up a couple of them headed in opposite directions. Still, this exemplied the kind of transition to which the house on Rittenhouse Square bore witness. The early 60s, the high 60s, if you will, led by the Beatles, full of a certain kind of youth and fun, were giving way to something powerful and worthwhile, but without the careless rapture.

Tuning In To Ralph Spoilsport

There was plenty of fun left, of course. There’s always plenty of fun. One of the things that made for fun was the unique comedy of Firesign Theatre, four amazing Angelenos. They were so sui generis, I am almost at a loss to describe them. Though they had their roots in radio, their real medium was the LP. They created densely-layered experiences in which, for instance, a character might be listening to the radio and then find himself inside the program he was listening to, and grow old or young during the experiences inside the program. You would quickly lose track of which experience was the frame and which the “real” world. The whole would be accompanied by outrageous wordplay, references to Joyce or Shakespeare or Conan Doyle. I’m dropping a small sample in an endnote.[7]

Firesign had just come out with its second album, How Can You Be In Two Places At Once When You’re Not Anywhere At All. We rapidly committed the entire first two albums to memory, doing the voices, capturing the rhythms. Firesign turned out to be as full of phrases applicable to any occasion as were Shakespeare and the Bible. We competed to see who could find the most applicable Firesign phrase for any given situation, leavening it with the occasional Dylan or Beatles quote. Otts recently reported to me that he had seen them in concert in recent years, and for some of their routines there were, in effect, “singalongs,” where everyone in the audience knew the words, just as we’d known the words.

So this was what life at 2209 sounded like.

It wasn’t perfect (too far off campus, for one thing).[8] But it was our first toehold in urban living. Not one of us came from a big downtown. Not one of us had lived away from both home and campus before. Not one of us regretted it. With all its imperfections, it was a house of song and laughter, a great first experiment in the independent lives we were getting ready to lead.

[1] As the YouTube comments point out, this is an artful mashup of the sound from the album, video from the Concert for Bangladesh, and little bits of Paul from other videos.

[2] It had just been made illegal the previous year. Considering that the Congress which had come up with that decision was the one funding the War, considering the the delegitimizing effect of the Draft then going on (about which this blog will shortly have more to say), considering that the use of the substance was observably doing no serious harm to any of us, is it any wonder we thumbed our noses? For some reason, marijuana wasn’t part of the package in our establishment; I think there were some other hallucinogens from time to time. There was all kinds of stuff going around. But since I never sampled it, I just never got au courant either.

[3] Fat chance. She was older than we, and I’m quite certain far more sexually experienced as well. She flirted, but we were not on her radar screen.

[4] Per Ian MacDonald, as ever my source on all things Beatles, the U.S. release was Wednesday, October 1, 1969. So this would have been Wednesday, Thursday, or just possibly Friday of that week. Revolution in the Head at 461 (3rd ed. 2007).

[5] Larry was a friend of Otts and Chuckie’s, and played in a band with Otts, and I think may have lived there after S. and I moved out in 1971. Plus Larry and Otts lived together in New York later. The point is, we were definitely keeping Carol in the family.

[6] Ian MacDonald makes some grandiose claims about this song, which makes it one of the relatively rare places we part company. “Nothing else on Abbey Road matches the Zeitgeist-catching impact of Lennon’s cover-breaking announcement, after two verses of faintly menacing semi-nonsense: ‘One thing I can tell you is you got to be free.’ The freedom invoked here differs from previous revolutionary freedom in being a liberation from all forms and all norms, including left-wing ones.” And he adds: “Enthusiastically received in campus and underground circles, COME TOGETHER is the key song of the turn of the decade, isolating a pivotal moment when the free world’s coming generation rejected established wisdom, knowledge, ethics, and behaviour for a drug-inspired relativism which has since undermined the intellectual foundations of Western culture.” Revolution in the Head at 359-60 (3rd ed. 2007). I’m sorry, I don’t think any of us who were busy rejecting some of the established wisdom, knowledge, ethics and behavior took this as a marching song.

[7] The title piece in the album discussed further above, How Can You Be In Two Places At Once When You’re Not Anywhere At All, begins with a parody of the TV ads of a Los Angeles auto dealer named Ralph Williams, here rechristened Ralph Spoilsport:

Hiya, friends! Ralph Spoilsport, Ralph Spoilsport Motors, the world’s largest new used and used new automobile dealership, Ralph Spoilsport Motors, here in the City of Emphysema. Let’s just look at the extras on this fabulous car! Wire-wheel spoke fenders, two-way sneezethrough windvent, star-studded mudguards, sponge-coated edible steering column, chrome fender dents, and factory air-conditioned air from our fully factory-equipped factory. It’s a beautiful car, friends, with doors to match! Birch’s Blacklist says this automobile was stolen, but for you, friends, the complete price, only two thousand five hundred dollars, in easy monthly payments of twenty-five dollars a week, twice a week, and never on Sundays.At this point, Ralph is interrupted by Babe, the persona whom we follow through the hall of sonic mirrors, who wants to buy the car, and suddenly we’re inside the ad, on a weird odyssey that will not end until 27 minutes later with Ralph reciting an adaptation of Molly Bloom’s soliloquy from the end of Ulysses. If you want to hear what I just quoted, click on the link at the head of this piece. For commentary and the text just quoted, go to The Firesign Theatre’s Big Book of Plays, 37-39 (1972).

[8] I can remember lugging my so-called “portable” typewriter to campus on foot across the Walnut Street bridge in the heat, or waiting for the buses in freezing snow. S. nominally lived in a dorm at the far end of campus (even though it was obvious we weren’t doing a very successful job of fooling her parents, but proprieties had to be observed on both sides), and sometimes I’d have to stay at her place, in her tiny cramped bed. And it often seemed as if we were really living, at least on the weekends, on the Penn Central Railroad, going up to my dad’s in New York or down to S.’s parents in Baltimore. Though it consequently sometimes felt more like a pied-à-terre than a home, it beat everything else hollow.

Copyright (c) Jack L. B. Gohn, except for commercial images