Someone Must Have Sent That To Kemp, Or, Not Enough Friends

Theme Songs Page | Previous Theme Song | Next Theme Song

Someone Must Have Sent That To Kemp, Or, Not Enough Friends

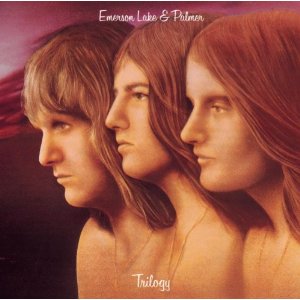

Abaddon’s Bolero, by Keith Emerson, Performed by Emerson, Lake & Palmer (1972), encountered 1973

Buy it here | See it here

I have always loved big, long, over-the-top and slightly apocalyptic rock numbers. I was passionate about the 7-minute version of Light My Fire, I was intrigued by the full version of In-a-Gadda-da-Vida, and even more by Procol Harum’s Repent Walpurgis, the Animals’ We Love You Lil, and (as these pieces will presently reflect), War’s Seven Tin Soldiers. Take a half-hour and listen to the links I’ve just provided, and see if you aren’t blissful afterwards. There’s something wonderful about a bunch of rockers casting caution to the winds and, musically speaking, saying what they really think, omitting nothing. But really thinking is key; one of the problems, for instance, with so much of the Grateful Dead’s oeuvre was that they went on and on and not everything actually had a musical point. Their jams were great for lying down in a field with hundreds of other people and letting your mind wander – an experience I had in 1969 – but not for seriously listening to.

Ham, Lamb & Strawberry Jam

One other piece that, for me, belongs in this pantheon of truly great over-the-top rock, is Keith Emerson’s Abaddon’s Bolero, a classic of the kind of music British rockers with formal training, synthesizers, and big hair were putting together then, featured on Emerson, Lake & Palmer’s 1972 Trilogy release. As the name indicates, Abaddon is in a musical form, the Spanish- (not the Cuban-) style bolero, suitable for classical framing.[1] Once you hear it, you know that it’s mostly true to classical form,[2] in that the triplet-heavy melody keeps repeating itself, but every time louder and with more bells and whistles, even cranking in a phrase from the folksong The Girl I Left Behind Me[3] before it’s all over – a total all-in effect, what the composer William Walton called “ham, lamb, and strawberry jam.”[4] And the whole effort is carried on Keith Emerson’s keening synthesizer, carrying a weird melody that seems to be constantly readjusting keys, although it ultimately keeps returning to the same place, a sort of E minor orientation. I still go nuts when I hear it.

The way I became familiar with the piece is a sort of a shaggy dog story of lonely young people leveraging what social assets they had, and making do with what was available.

Catchment Area

The natural catchment area for friendships for us when we got to Baltimore and Hopkins would have been the graduate English program. And we did make a few friends there, most notably a fundamentalist Christian couple who enjoyed our company even though they seriously believed we were going to Hell. (They belonged to something called, with no sense of irony, the Church of the Open Door.) But the husband was much better at playing the Department’s political games than I was, and this, much more than theological class differences, did in the relationship after a year or two.[5] Another couple, Canadians, in a Gentile/Jewish relationship like ours that might have afforded more of a basis for sharing, were so devastated by their own problems (the Jewish parents weren’t cool with Junior dating the shiksa) that they became socially unavailable in time.

So we had to look elsewhere. Most of our other connections in this town came from my wife’s family, which was local, but not thickly populated with S.’s contemporaries whom we could have made friends of. But I had a few as well; as I’ve mentioned before, I was a legacy of the Hopkins English program from days of old. There were some relics of the world my mother and stepdad had inhabited as well. One was Martha.

Martha’s Kindness

In attempting to describe Martha I find I must first attempt something else: the world of what we called the Blue Hairs. This won’t be easy. Let me start by saying that in its heyday, Baltimore had been a town with a very definite Society, a world of genteel, often but by no means always wealthy folk whose social lives largely took place in the area roughly running two miles to the north of the Hopkins Homewood campus. That world had largely ended before I turned up in 1971, but the survivors of it, mostly elderly women, hung on, many of them in the large and gracious apartment houses along University Parkway and nearby. Baltimore may have been (barely) a Northern town but the Blue-Haired ladies definitely had Southernness stamped on them, whether they spoke with a drawl or not. Few had bloodlines that ran North, most had connections to great Southern families. They tended to have elderly doctors and elderly servants and elderly bankers, and memories that stretched back generations, and ideas about race relations that did the same. But they were also tough and strong and practical, and in their own way quite admirable.

I remember making my first acquaintance of one literally the moment I arrived in Baltimore, parking a U-Haul truck beside the fire escape steps to our new apartment – not leaving adequate room in the alley for her to get her car past while visiting a doctor. “What the hay-ull” she asked “do you think yoah doing?” This, the voice conveyed in only a few words, was an admonition from someone accustomed to being obeyed. I think I moved the truck.

I said that some of these ladies were wealthy, but not all. One way into the sisterhood without being rich was through Hopkins connections. Martha was of that ilk. She had been a humanities librarian at Hopkins during my parents’ glory years, and had been very helpful to and close with all the graduate students of their era. My folks insisted that I look her up when I got to Baltimore. She was not wealthy, but she drank sherry with the Blue-Haired ladies who were. She had a voice cured by a lifetime of cigarettes and probably significant alcohol intake, and I suspect her life had also been shaped for the worse by spending it in the closet, but I have zero proof as to that.

In any case, she took a parental interest in us as she had in my parents. And during the summer of 1973, after we had been two years in Baltimore, she did us a very important favor, providing a connection to Inez Malone. It was a wonderful piece of matchmaking. We had complementary needs.

Working for Inez

Inez was the widow of the great Hopkins philologist and linguist Kemp Malone, former president of the Modern Languages Association, specialist in northern European languages, explicator of Beowulf. “Kempie,” as my mother called him, had long been retired, but had died only weeks after we arrived in Baltimore. He left behind not only Inez, but two adjoining row houses on Maryland Avenue whose double-basement was full of thousands of books. And Inez decided to convey all of those books to Emory University, her husband’s alma mater. Which meant she needed to have them catalogued.

Both I and my wife were literary people, and my wife, upon leaving Hopkins after one year, had gone to library school. Between us, then, we had the talent to assemble the catalogue. I think Martha was aware of my unsatisfactory job the preceding summer (also written about in these pages), as well as of S.’s librarian credentials, and put us all together.

Now, of course, Inez was not a friend, not in the sense of a contemporary we could hopefully grow up alongside. But she was definitely someone to know. She was a Blue-Hair who had strayed a little off-course geographically, as there were no fashionable blocks of Maryland Avenue then, and south of Hopkins was the wrong side of the tracks. But she stuck it out. And she made a social event of our cataloguing experience. We would break in the middle of each day, and she had the maid put together some kind of genteel collation for us, old lady cakes, maybe tea, that kind of thing. We would come upstairs from the basement and enjoy them with her. She was entertainingly outspoken, if given occasionally to malaproprisms; she sometimes seemed to be losing a little control of her speech.

They Don’t Collect ‘Em Like That Anymore

It was quite an experience helping S. catalogue those books. The collection legitimately took most of the summer to put together, being in effect three collections (or at least so it seems in my recollection): what must have been damn near a reference set of all important works of and reference sources on Germanic philology, a more general literary collection, and odds and ends.

None of the three would exist today.

As to the Germanic philology collection, there are surely still linguists toiling in the fields of Old Norse and Old English and their kin, but just as surely no one now devotes the vast resources necessary to acquiring every book, every journal, every festschrift; I’m pretty sure Malone had them all, or something pretty close. The more general literary collection, more of a reader’s than a writer’s collection, would now largely be on Kindles. And the odds and ends were ephemera whose time has definitely passed since then, and had probably passed already by the early Seventies: I remember city directories (which no one creates now, or at least not in hard copy) and naughty nature magazine erotica.

Of the latter, I remember thinking even at the time that leaflets with nude young ladies tossing around beach balls was the strangest way to satisfy one’s pornographic needs (the word “porn” wasn’t in common usage yet). I’d grown up with Playboy, and when I started sorting the mail for Bennett Hall, back at Penn, to earn a few bucks, I’d come upon some of the professors’ porn, which was of the far more graphic Tab-A-in-Slot-B variety. This stuff was almost too quaint to be sexy. Since we had to decide whether to catalogue it, we asked Inez about it, and she commented innocently: “Someone must have sent that to Kemp.” Yup, in a plain brown wrapper, as I’m sure Inez knew damn well. But give her credit for defending her man. I don’t recall whether she told us to catalogue the nature mags or not, however. The answer can be found in the catalogue, which is still preserved at Emory University, but at the Emory library’s imaging rates it’s too expensive to digitize the list and confirm it one way or the other.

Introduced to David

Inez also did one other thing for us, again by way of making connections. Through her own Confederate roots (she was a Chastain of, I think, Richmond), she had been asked to keep an eye on a Southern young man whose career had brought him to Baltimore. She either had David to dinner with us or had him drop by during one of our mid-day teas. Based on that, we struck up a friendship for a while.

David was a recent graduate of Elon College, and he had taken some kind of sales job up north.[6] Per Wikipedia, “In the early 1970s, Elon was an undergraduate college serving mainly local residents commuting from family homes, attracting ‘regional students of average ability from families of modest means.’”[7] David probably fit that description to a T, which meant that he had little in common with S. and me, products of Ivy educations pursuing advanced degrees, products of a more cosmopolitan north. David had been a frat boy, to boot.

But his apartment was only a block away from our apartment, and he was lonely, and we were lonely, so, as I say, we tried to patch together a friendship. So we sat in his living room or we sat in his, drinking Mateus or Cherry Kijafa or some dreadful thing that young drinkers or limited means and even more limited taste drank in those days, and tried to make something happen. One time-honored way to do that was to play records together. His collection was lacking the brainy stuff, but of course, as you’ve been anticipating since the beginning of this essay, one of the records he played us was Trilogy, the Emerson, Lake & Palmer album that contains Abaddon’s Bolero. I took it home and taped it, and must have played Abaddon’s Bolero dozens of times, meaning that I must have rewound it as many times. I really loved the song.

What I’ve Forgotten

I’m ashamed to say that after this recollection of David, that is to say, after remembering David lending me the record, I don’t remember a thing. In my work, thirty years later, I have represented and advised dozens of young men and women who remind me of David, engaged in sales of medical or engineering products, constantly in conflict over territories and commissions, and very, very geographically transient. I’m guessing he was transferred or changed employers and moved along. But in my memory all that remains is David-who-lent-me-the-ELP-album. He deserves better than that, I’m sure, but it’s all I’ve got to give him. Sorry, David.

As for Inez, her husband’s library was donated to Emory University in 1974, right on schedule. She was reportedly in her glory at the reception for the collection, although with her characteristic slightly shaky diction, she started out: “Kemp Malone had a long and a happy wife.” I think she had it more right than wrong. The library, especially its Germanic philology side, was a family project, nature mags and all, and she had brought the project to fruition by transmitting it to further generations of scholars. And it did make her happy.

Archibald MacLeish wrote that a poem should not mean but be. I never endorsed that view entirely, because much of poetry does mean, in fact most of it does. Actually, the proposition is more apt to be right with music than with poetry. I believe Abaddon’s Bolero is one of those pieces that does not mean, but just is. The name Abaddon is that of an angel of destruction referenced among other places in the Book of Revelation,[8] though his name is also used as a synonym for Hell. But the bolero does not seem to be “about” destruction or the torments of the damned. It is a cathartic thing to sit through the number to its over-the-top end. But I wouldn’t call it hellish. I suspect Keith Emerson chose the name for its evocative qualities and just its strangeness. Because, really, strangeness is the key to the experience of the song.

Saying Thank You

A very pleasant kind of strangeness, I may add. Thanks to Martha, and Inez, and David.

[1]. A list of classical settings of the bolero, including ones by Chopin, Debussy, and Bizet, as well as the inevitable one by Ravel, along with the distinction between Spanish and Cuban bolero, is to be found here.

[2]. Although I understand that three-beat boleros are more common than the four-beat variety executed by Ravel, and by Emerson, Lake and Palmer. See, e.g. this online music dictionary, that only acknowledges the three-beat bolero.

[3]. Sort of the way Procol Harum dropped Bach’s Prelude in C Major into Repent Walpurgis.

[4]. Actually, this was Walton’s stylistic note on the opening of his piece Shakespeare Suite: Con prosciuto, agnello e confitura di fragiole. Or so, at least, it is reported in Muir Matheson’s 1964 liner notes to a recording of Music from Shakespearean Films.

[5]. Now that I come to think of it, these issues may not have been dissimilar. What the graduate English program did with stipends at the end of the first couple of years bore more than a passing resemblance to the rewarding of the faithful and punishment of all others at the Last Judgment. And we know that, however mingled we mortals may be in this life, in the fundamentalist Christian vision, there will be no fraternizing of the Elect and the Damned in the hereafter.

[6]. Yes, fellow-Michiganders, I know that for us, the initiated, “up north” will always have a precise meaning that few strangers will grasp, and that technically speaking I’m misusing the phrase.

[7]. Quoting a study of Elon (published by Hopkins Press, interestingly). The quotation goes on to say that nowadays, Elon University is a much grander institution. I have no reason to doubt this.

[8]. In Rev. 9:11, Abaddon appears as the leader of a horde of stinging locusts. “They had as their king the angel of the abyss, whose name in Hebrew is Abaddon and in Greek Apollyon.”

Copyright (c) Jack L. B. Gohn, except commercial artwork