Deconstructed

Theme Songs Page | Previous Theme Song | Next Theme Song

Deconstructed

Lean on Me, by Bill Withers (1972), encountered 1972

Buy it here | See it here | Lyrics here | Sheet music here

Certain conversations change your life. Let me start with one that did, but in exactly the wrong way.

It is a grey and damp March Saturday in 1971. A gentleman with close-cropped gray hair named Earl Wasserman and I are walking the streets of West Philadelphia. It is an open-air interview for a spot in next year’s Graduate English Program at Baltimore’s Johns Hopkins University, which Wasserman runs.

There’s History Here

This is a man who should be on my side, almost no questions asked. Without him, my life to this point would have been completely different, and he must know this. Back when he and my father were young faculty members together at the University of Illinois, they and their spouses formed a foursome. Wasserman, an enthusiastic proselytizer for the academic program he came from, Hopkins Graduate English, had persuaded my mother to matriculate in that very program should she return East, as she eventually did. And it was there, on or around the steps of Gilman Hall, my mother met the man who, about a decade later, would become my stepdad. Ernie Gohn, the stepfather who did far more than his share of the heavy lifting in raising me, would earn his doctorate in that program a couple of years after he and Mother met. Wasserman knows all this history.

And incidentally, here you can see, on those Gilman steps (from the Fall of 1946), the students my mom joined, including my mom herself, in the middle of the front row, with my stepdad right behind her. This was three years before my mom and father even produced me.[1] In the gossipy world of scholars connected almost umbilically with this program, whatever unconventional goings-on lay behind that photo are history any faithful alum like Wasserman, especially an alum who pushed my mother into the program to begin with, must have heard. And he should be helping to write the next chapter of that history, right?

And I am the kind of student any graduate English program should welcome. Great grades, working familiarity with Old English, Middle English, and the contemporary stuff and everything in between. Earning bachelor’s and master’s degree simultaneously.

Not On My Side?

Yet for the moment it doesn’t appear he is on my side. What do I think I’m up to, applying to a department where there are twenty trying to get in for every slot? And what is this business in my application where I say I’d like to do some creative writing in after life, along with scholarship? Am I aware that I can’t possibly do both? OK, so C.S. Lewis did it; I don’t think I can, do I? Am I really unaware that scholarship consumes all a real scholar’s time and loyalty? Johns Hopkins only wants real scholars who will produce great scholarly works. Am I going to commit myself to that goal, or will I skulk in, pretending that I am going to produce these works, while actually planning to go off and fritter myself away being creative, when there are so many worthy people in the world who would make better use of the opportunity?

Now, if I agreed with Wasserman’s premise, I’d feel worse about trying to placate him. But I don’t agree; oh, maybe I can sense the experience that lies behind his pronouncements and the faint traces of benevolence in his effort to send creative writers elsewhere. But I think I’m more capable than Wasserman allows. I think that, with focus and drive, I really can do both the creating and the scholarship. But he won’t let me say that, so I kind of lie and downplay parts of my ambition.

Perhaps I succeed; I am admitted two weeks later.

Have I really fooled Wasserman? I don’t know, but I doubt it. My best guess, looking back, is that he let me in on account of auld lang syne, because of the connections with my mom and my stepdad — and my father. And he was probably hoping for the best, the best being that he could eventually ease me into his ascetic scholarly mold. As for me, on the strength of that conversation alone, I should have run like hell in the other direction, because even if I didn’t know yet exactly what he wanted, I had sufficient warning that it would be something I could never provide. Each of us thus said yes when we should have been saying no. Call it fate.

As is always the case, it wasn’t sheer cussedness alone that led me to make that choice; there were also various sensible considerations. The pattern of acceptances and financial offers I and my fiancee received made it clear we were either headed to my home town of Ann Arbor, or to Baltimore, from whence she came. And slightly better money seemed to be coming from Baltimore.

Deconstructed

But it proved to be nothing like what I had expected. Partly this stemmed from me unwarrantedly extrapolating from what I knew. I’d assumed that all graduate English departments were like Penn’s: lecture format (where the professor did much of the heavy lifting) with the occasional seminar. Hopkins was all seminars, all the time. We were expected to do multiple papers in each course, read them to each other, and comment (and if you think that brought out some unhealthy competitiveness, you’re right). But those were the superficial dissimilarities. Wasserman had been less than candid too, it seems, about something even more important. Hopkins, it emerged, was all about criticism, not scholarship. And so, in our seminar papers and everywhere else, we were expected to spend more time talking about the published criticism than about the works being criticized. This brought to my mind the picture of a man bent over, playing tic-tac-toe in the dust, ignoring a spectacular sunset going on behind him.

It wasn’t just the emphasis on the criticism; it was the kind of criticism. Unlike what my mom and stepdad had encountered with their band of brothers and sisters in the 1940s, the Hopkins Grad English program of the 1970s had dedicated itself heart and soul to turning out Deconstructionist critics. And what (you may ask, if you’re not in the know) is Deconstructionism? I’ll tell you: I can’t tell you. There is no there there, no definition by definition. There are certain tenets: texts have no fixed meaning; we interpret them according to our sense of reality, but that sense is just another text. Criticism is therefore the creation of texts about texts, and the most creative creations of texts about texts are those that subvert the apparent meaning of the texts under discussion. Hence critical creativity dwells most consistently and most laudably in destruction. Or, as they preferred to call it, Deconstruction.

My interest in scholarship, then, was not merely different from the interests of the professors; it was an affront to the premises on which they were basing their careers. I sought to learn facts about literary works that would help us understand what they actually, objectively meant. That quest that presupposed a conviction that works had objective meaning, that their meanings were tied to their authors’ lives and intentions, and that lives, intentions, and meanings in many cases would be knowable. This was anathema to my professors, or something worse than anathema: belle-lettristic.

And even that wasn’t the whole problem. I came to realize fairly quickly that a lot of the writers and books I cared about weren’t considered worthy to be on the syllabus. So-called minor genres that I’d been able to write about freely at Penn (mystery, science fiction, spy fiction, children’s literature, rock lyrics) were off-limits. A destructive radicalism in reading was thus put at the service of a conservative and snobbish selection of what to read.

Puff Puff

You might expect that with such radicalism would come at least some kind of excitement, no matter how ersatz. Sorry to disappoint you. I present a transcript of a moment chosen almost at random from the seminar table talk of one professor I had. Imagine him smoking his pipe. “When…I…was…in…(puff)…(puff)…college… …(puff)…(puff)…I had… … a friend…(puff)…who wrote… …(puff)…I get tired… … (puff)…(puff puff)…Is that a sign…(puff)…of…(puff puff)…maturity?” You could go mad waiting for the end of two sentences like those, and then mad again dealing with the attitude they conveyed.

The acme of the Hopkins Grad English universe was the Tudor Stuart club, a paneled room on the third floor where monthly evening meetings took place. I attach a 2011 photo of the room, not much changed from how I remember it then. Attendance was de rigeur, though they softened the blow by laying out beer and the makings of cold cut sandwiches. But then you’d have to sit through lectures by visiting Deconstructionist dignitaries. If a lecture were graspable using ordinary logic and common sense, it was deemed a failure. There were few failures. Instead, there would be the most impenetrable prose you ever heard. After an hour of that, the questions would start. People, mostly faculty, would pose questions, many in the same diction as the lecture, and you’d have to sit through that for up to another half hour, until dismissed.

There were those who drank the Kool-Aid, who claimed to get it. These were the ones the professors rewarded with continued stipends and bona fide job recommendations (more about that in a later entry). I neither claimed to nor did.

And They Hated Me Right Back

I caught on quickly that this wasn’t a congenial place for me, writing my parents at the end of September that I hated it. Evidently the feeling was mutual. At the beginning of February, I received a letter from the department chair advising that “On the basis of the necessarily limited evidence available, we have some doubts about the quality of your work as of this moment.” My wife got a similar letter. In my case, the department ultimately relented, and allowed me to stay with a stipend (I was upgraded to “satisfactory” in May), but it would extend no stipend to my wife. She stepped down (and went on to better things).

In light of these developments, I wrote to a friend who’d gone to Yale:

Words have not been coined to describe the awfulness of this place…. They don’t have any money and they’re doing people dirt, right and left.[2] Since there are no grades, we have no objective standards to point to in our own defense: all they have are subjective analyses of us on file with the chairman which we aren’t even allowed to see…. Classwork counts for nothing, and so the phenomenal string of papers we have to turn out like sausages is the essential means the student has of establishing his worth. But around here you’re expected to become somebody’s disciple … and your papers had not only better be done well, but they had better coincide in their findings with the professor’s own opinions.So I arrived at year’s end battered and bruised. My value as a literary man had been impugned, my earlier-described vision of my wife and me as soaring through the clouds together sharing an academic career had crashed to earth, and I was in need of ready cash. At least there was a partial and temporary solution for that last one: My father-in-law called in some favors and landed me and my brother-in-law a job to split: driving a Mister Softee truck in Anne Arundel County, a marshy enclave west of the Chesapeake and south of Baltimore.

It was certainly a different experience, I’ll say that.

The Power of Positive Ice Cream

[3]

[3]

Different, but not much of an improvement. In those days you could fairly call that area (Glen Burnie and Severna Park) a redneck suburbia. I drove up and down neatly-platted streets trying to sell soft ice cream, listening to a maddening jingle played over and over again on the speaker mounted above my cab. The ice cream may have been cold, but the cab was hot, and I sweated off over a dozen pounds. I was being paid a small base plus commission, incentivizing me to sell, sell, sell. But redneck or not, these were neighborhoods to which freezers had come, dampening demand, and the trucks were old and prone to breakdowns, frequently killing outright my ability to meet what demand there was.

You would not have guessed the existence of either of the problems listening to the franchisee, a man named Marshall. In Marshall’s imagination the sky was the limit, and mechanical troubles were to be overcome with a positive attitude, not expensive repairs. Yet ice cream trucks contained two complete mechanical systems (truck and kitchen), each with a plethora of moving parts. Old systems are apt to go on the fritz; that’s just the way of it. Your product was perishable, and if you couldn’t turn that mix into ice cream and those bananas into splits, they had to be written off. If you had a flat tire, or the ice cream machine went down, you were out of business until further notice. Marshall thought (or at least pretended to) that if we were really committed on a deep spiritual level to sales, we could magically move ice cream irrespective of whether the trucks could budge or the ice cream could dispense.

Marshall had a trophy younger girlfriend, Roxanne, who had been a beauty queen. Marshall had made her vice president of his company. It was painfully obvious to the rest of us that Marshall had mistaken whatever he saw in her for business acumen, but that she possessed neither more nor less of that than the rest of us, and her beauty and certain degree of spunk could not change the overall direction of an undercapitalized business dependent on a badly depreciated truck fleet. We wanted Marshall to spend less time looking communing with Roxanne and more time looking at the fleet. Marshall’s starry-eyed embrace of motivational nostrums could not substitute for an outlay of cash, and somehow he couldn’t see it. And he probably couldn’t have afforded it even if he had seen it.

The Power of Nature

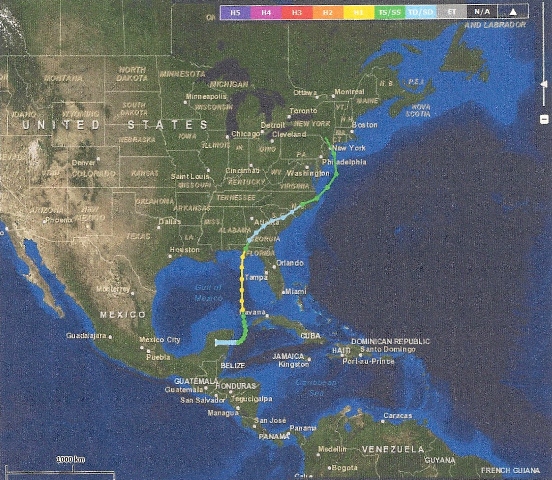

I obviously did not share Marshall’s rosy vision of the transformative powers of pure sales karma, but I did believe in getting to work on time (an improvement over my views working at Ford three summers before, written of in an earlier entry), and so, on Thursday, June 22, 1972, even though the weather was bad, I was trying to fight my way in. I’d heard that there was a hurricane around but not exactly in Maryland. Heading out to the car, I felt a lot of rain, but nothing like hurricane winds. So I optimistically set out for Glen Burnie and the Mister Softee compound. Bill Withers’ annoying April hit, Lean on Me, was playing on the radio as I cruised downhill on the Baltimore-Washington Parkway toward the wetlands that constitute the banks of the Patapsco River. It was when I got close to those wetlands that I realized things might be a little different today. There were no wetlands to be seen at all, just water that came up disconcertingly close to the highway — where there ought to have been at least 10 feet of grade separation. And traffic had almost stopped. As I got close to the next interchange, where I was supposed to exit the Parkway and get on the ramp for the Beltway southbound, there were police cars with flashing red lights, waving us off.

I guessed that there was something wrong with the Beltway, but I assumed I could find an alternate route. So I not only kept on going (I had no choice about that), but also kept trying to get to work. And that was the beginning of what (in memory at least) was a three-hour ordeal, in which, through increasingly powerful rain, I was seeking a way to Glen Burnie on back roads, roads I did not know, roads I was sharing with far too many drivers, roads that kept ending in roadblocks. I don’t know how long it took me to figure out that Hurricane Agnes (they were calling it that even though it was no longer at hurricane strength) was simply going to keep me out of Glen Burnie altogether that day, and that, however great a sales opportunity might be presented with power out all over the peninsula and people’s freezers out of commission and their dark houses driving them into the street, I was never going to get there to capitalize on it.

[4]

[4]

When I did realize it, though, I also realized that it had been my choice to put myself out here, against advice, that I was in parts of the back of beyond I did not know, getting lashed by rain, and that, by this time, the paths back to what was comfortable and familiar might be closed.

Stuck Here

Even after two semesters at semiotically insane Johns Hopkins, I recognized a metaphor when one was rapping me on the knuckles. And I also recognized that Lean on Me, which was played at least once again on the radio (it would become a Number 1 hit in July) as, against all odds, I gradually worked my way back into Baltimore, was a perfect metaphor for the metaphor.

Was there ever a more ugly or simple-minded song? Starting with that opening piano cadence, an inverted C chord, followed by the hands simply moving up and down on the white keys without changing their position, and just seeing what happens. The verses doggerel, poorly scanned. A bass line that at one point is sketching out a different chord from the one being played by the piano, and not because the bass player is being inventive, but because he apparently isn’t listening. And lyrics that relate two notions, though they do not explain the relationship, because they can’t. One notion is that we need to help each other out, and the other is “there’s always tomorrow.” Tell that second one to the three children in Maryland whose car overturned in the floodwaters of Hurricane Agnes and drowned. They didn’t get even one tomorrow. And if there were always tomorrow, then how important would it really be for people to help each other out? Wouldn’t they all be assured of a tomorrow regardless of whether others lent a hand or not?

I could beat this horse for a long while, but it’s dead and I’m done. The point is, that song just made it perfect. I knew from having my ear well trained over the preceding decade what a good song sounded like. I knew what the proper approach to literature looked like. I knew that mysticism didn’t sell ice cream. And now I was in a world where no one who ran the show cared what I knew; they thought they knew better and were going to do it their way. And I was going to have to be a part of that world for a while.

I just had no idea on that wet June day how long I would be stuck there. But stuck I was.

[1]. In answer to the obvious questions, my mom and father were in the midst of an extended separation at the time the photo was shot. They were back together later, from 1948 to 1953, during which period I turned up. A story to tell at greater length somewhere else.

[3]. Image source here.

[4]. This is a screen capture; the interactive map from which it’s taken is on the National Oceanographic and Atmospheric Administration’s website here. On the source map, you can follow (at whatever scale you like) how Agnes moved up the coast, and make out why the storm was initially thought not likely to cause problems on June 22 at the top of the Chesapeake Bay.

Copyright (c) Jack L. B. Gohn