The Greatest Song(s)

Theme Songs Page | Previous Theme Song | Next Theme Song

The Greatest Song(s)

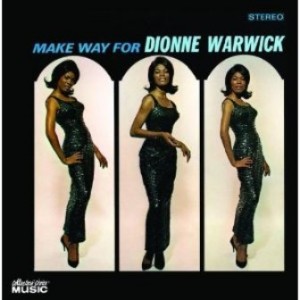

Walk On By, by Burt Bacharach and Hal David, Sung by Dionne Warwick 1964, Encountered 1964

Trying to talk about my encounter with the rock and pop music of the 1960s forces me to resort to metaphor. Sixties music smacked me in the face, it rocked my world, it turned my world upside down.

For all of that, it was a gradual process, though it started with a bang.

As my earlier pieces make clear, I was not much into 1950s rock – not in the 1950s, anyway. Some of my friends were, and what the 1960s held in store for them musically cannot have been quite as overwhelming as it was for me. I was behind the curve.

To catch up, I first had to picture myself as someone capable of being receptive to that kind of music. And initially I couldn’t. My failure of imagination was due to two rather different factors.

First, there was the force, for good and ill both, of my parents’ tastes. If you’ve read about my earlier Theme Songs, you know the sorts of things I had been listening to: mostly a selection from what my parents had made available to me.[1] It was musically nourishing, all right, overly so in fact. Up to that point it had left me too fulfilled to look around. That was coming to an end now. Though I didn’t recognize it just yet, my parents had “gone about as fer as they could go.” Oh, my stepdad might buy my mom the latest original cast albums from Broadway musicals, but he basically left off with early Sondheim. Judy Garland and Marlene Dietrich, about whom I’ve already written, were still singing, but doing nothing new and exciting.

My folks’ radio stations were WJR in Detroit and the University of Michigan station, WUOM. WJR, to the limited extent it was about music at all, was kind of middle-of-the-road-ish, and WUOM was for classical music, educational fare, and Michigan football. There was nothing wrong with them, but again, they were just not breaking new musical ground.

That was okay with my folks: they didn’t want any truck with new musical ground. And here we come to the second factor I had to overcome: parental disdain. Both my mom and my stepdad entertained a visceral revulsion toward the ever-so-slightly-oppositional-defiant style of 1950s American youth icons (think James Dean, Elvis Presley, and Marlon Brando). To them, this wasn’t a minor matter of style, it was a fight for the very soul of our society. Such revulsion not only left out of the question any serious parental attempt to listen to or hear what the first generation of rockers were providing, but also extended to expressions of disgust in which I was expected to share.

And, out of sheer loyalty, that’s what I did. For a while. My parochial school, which covered twelve grades, had but one cafeteria, and I remember sitting there as a grade schooler in the late 1950s and making scornful remarks about the high school girls in their signature bobby socks and saddle shoes (standard wear for girls of that era who might be listening to Elvis and his ilk) – about them and their music – really for no other reason than that that was what my mom would have done. Nobody else ever joined in, but I never took the hint.

Becoming an adolescent would inevitably entail my beginning to think for myself. And that, in turn, would inevitably involve me in an embrace of a lot of things my mom hated. All the same, one generally does these things by steps. And I’m pretty sure that the first step of my initiation came through WJR, the station my mom with all her musical prejudices found comfortable to listen to almost every day.

In 1964, however, WJR opened up a little bit, rehiring (from a spell in San Francisco) the slightly adventurous DJ and all-around radio personality J.P. McCarthy, who had both the Morning Music Hall and the Afternoon Music Hall programs. McCarthy, if I remember correctly, was not orthodoxly opposed to new sounds. And a lot of new sounds were happening in 1964. April of that year saw Barbra Streisand charting with People, and Dionne Warwick charting with Walk On By,[2] both of which I am pretty certain I first heard on McCarthy’s program.[3] I remember Mother commenting with astonishment but not disgust at the then-new Streisand phenomenon. I don’t remember her saying anything about Warwick.[4]

If she had looked into Warwick, though, she’d have known that Warwick was the test pilot for many of the songs produced by Brill Building tunesmiths Burt Bacharach and Hal David, but also that Bacharach was just coming off a six-year occasional gig as the conductor for – Marlene Dietrich’s orchestra! Walk On By was full-throated 60s pop, but it was also not rock, as one might expect from Bacharach’s Dietrich pedigree. (That non-rock pedigree may have had something to do with the song appearing on WJR.)

I remember being blown away by both songs, but being aware, immediately, that Streisand’s and Warwick’s hits came from entirely different musical countries. The former was my parents’ music continued, maybe freshly repackaged. The latter, on the other hand, was – well, what was it?

That is actually a surprisingly tough thing to say. Here’s how the very articulate Alec Cumming phrases it in his notes to the wonderful 3-CD Bacharach anthology The Look of Love (1998):

“Walk On By” has the ability to stop you dead in your tracks. Maybe it’s the flügelhorn. Or those pounding doubled-piano breaks. Or maybe it’s the echoed background singers, with their desperate little joke (“Don’t. Stop. Don’t. Stop.”) Or the strings that at one instant swell up like a sea of tears, then next moment slink away.

In less than three minutes, Bacharach takes you on what seems like a compressed tour of the whole territory of heartbreak, courtesy of his amazing mastery of the pop orchestra. He composes, he orchestrates, he conducts, and he creates a sound that is uniquely his, one I would come to know as the quintessential sound of 60s pop.

Part of the wonder is the rhythmic uniqueness of it. When you look at the sheet music, it seems to be in 4/4 throughout. But the introductory rhythm break ups the bars in a way you can only hear, not count. It feels as if there’s a shift every half-bar, as if fragments of bars are being fused in weird places. It should slow the singer and the flügelhorn and the strings down to a halting crawl, but somehow it propels them to lyrical heights. Don’t ask me how he does it. Nearly half a century later, it still seems wondrous to me.

Which is not to say it’s all about the composer and the orchestra. It’s also about the lyricist and the singer. Especially the singer. In commenting about each of them, though, I’m even more at a loss for words than I was in talking about the music. What can one say about utter perfection? For once I am not even going to try.

In the years since then, I’ve heard lots and lots of songs. This one remains my very favorite.

And when I first heard it, early in 1964, as a high school freshman, I knew immediately I’d found something my parents knew nothing about and wouldn’t care to, but that I desperately wanted more of.

And so, at age 14, I started to explore.

[1]. Oh, I had made my parents buy me the occasional 45 hit that I’d been exposed to by one or another friend or at school, or maybe even heard on the radio stations my folks listened to. Examples I can think of are Sixteen Tons by Tennessee Ernie Ford (1955), Oh-Oh, I’m Falling In Love Again by Jimmie Rodgers (1958), and The Chipmunk Song (Christmas Don’t be Late) b/w Alvin’s Harmonica, by Ross Bagdasarian/David Seville/The Chipmunks (1961), not to mention the Singing Nun LP (1963). But none of these qualified as precursors of the pop and rock revolutions.

[2]. There is an excellent YouTube slide show of the complete song here.

[3]. Also three or four Beatles songs, but that’s another story (see the next entry). I don’t think I ever heard the Beatles on WJR.

[4]. Warwick apparently became Warwicke in the 1970s.

Copyright (c) Jack L. B. Gohn