“Patricia”

Theme Songs Page | Previous Theme Song | Next Theme Song

“Patricia”

I Get A Kick Out Of You by Cole Porter (1934), Sung by Eileen Rodgers 1962, Encountered 1962

In the last two weeks of August 1962, I traveled to New York to visit with my father. At this stage of his life he was teaching econom ics in the Columbia Graduate School of World Business. He had just published his most important book, had either received or was about to receive his full professorship, and was three years into his successful second marriage. He and my stepmother had recently bought a country getaway home in Tannersville, up in the Catskills. In short, I was visiting a man at the top of his game. After years of struggle, it was all going his way. And he wanted to share it with me.

ics in the Columbia Graduate School of World Business. He had just published his most important book, had either received or was about to receive his full professorship, and was three years into his successful second marriage. He and my stepmother had recently bought a country getaway home in Tannersville, up in the Catskills. In short, I was visiting a man at the top of his game. After years of struggle, it was all going his way. And he wanted to share it with me.

I could sense the excitement. And it rubbed off onto three things that I remember happening.

One was that he took me on the Staten Island Ferry to pass the Statue of Liberty, and there’s a picture of me doing that. It was a big gulp of the sheer glamor of the town, and I was duly impressed.

One was that he took me on the Staten Island Ferry to pass the Statue of Liberty, and there’s a picture of me doing that. It was a big gulp of the sheer glamor of the town, and I was duly impressed.

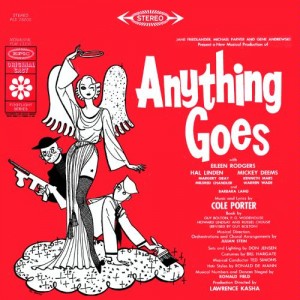

Another was that a girl I’ll call Patricia and her mother visited. And a third was that my dad took me to see the revival of Cole Porter’s Anything Goes off Broadway at the Orpheum Theatre and bought me the album. And the second and third of these events converged somehow in my mind.

I was now a rising eighth grader. Back in my fifth grade, Sister Rose Irene, one of those charismatic teachers who makes indelible contributions to your growth, had decided that four of her charges were getting too little out of the grade school library, and had sent us up to the high school library instead. That began one of the great friendships of my youth.

The four of us, two boys and two girls would not just climb the stairs to mingle with our elders, we began to hang out together at each other’s houses. One of them was Patricia, a slim, tall, thoughtful girl. We talked on the phone a lot, and with her I could talk about almost anything. I visited her home sometimes even if there were only two of us, and not the foursome. And by the beginning of eighth grade I was beginning to have feelings for her. There’s a photo of us here.

I’ve described in my previous Theme Songs entry where I was in my thinking about girls. Perhaps I’d moved on just a little from that stage to the moment I am speaking of, now that I was turning Patricia over in my mind. Together, we’d been picked out as special. Having her as a friend, someone with valuable things on her mind to share, and to appreciate the most important things about me – that was of far more moment than the thought that, for instance, we might be smooching some time.

And what was one of the most important things about me then? Why, the fact that, though I lived in Ann Arbor, I had something of a second life, with a dad and stepmom in Manhattan. So when it befell that Patricia and her mom would be visiting in New York at the same time as I, it was like manna from heaven. I could bring Patricia into my New York life! She could see (and hopefully admire) that side of me. I agitated with Patricia’s mom and my dad for a meeting in Manhattan. And the parents complied.

My dad lived on the Upper West Side in a University-owned apartment, so Patricia and her mom came up there. We were a couple of blocks away from the Riverside Cathedral, the nondenominational Gothic structure that towers over Morningside Heights. So we all went sightseeing there. You’d think, considering how important it was, I’d remember more details of that visit. But that’s memory for you. I don’t remember much about it. I remember climbing the steeple with Patricia and her mom. I remember being very excited about the whole thing. And that’s about it, at least as far as events go.

But as far as feelings go, there’s definitely more. The excitement didn’t go away. Patricia may only have been a girlfriend in my mind, but now she was in on my second life. We could talk about it, which was huge. It made me long to get back to our phone calls, when I got back home.[1]

In the meantime, though, I was also an avid theatergoer, a taste my dad shared. And so down to the Village we went, to the Orpheum,[2] to see a revival of Cole Porter’s Anything Goes. Although you could hardly grow up in that era with parents marinated in their own generation of pop culture and not be exposed to Cole Porter, you could (and I did) do it without listening to the songs very hard, and certainly without registering his name. Porter wrote first and foremost for the stage, and when you heard his songs in context, a lot of things swam into focus and you would not forget the name any more. Percy Hammond of the Herald Trib[3] commented on the original 1935 show that Porter’s songs were “ribald and sentimental.” That nails it. Much of the best of Porter is ribald and sentimental all at once. That’s a combination that chimes with the deepest vibrations in a young adolescent’s developing soul, whether or not he recognizes the receptors for them in his mind.

Although there’s nothing x-rated about the lyrics,[4] and high schools can and do put on productions of the show without offense, when you see the whole package (chorines dressed as angels but fluttering their diaphanous dresses like strippers, a revivalist anthem, Blow, Gabriel, Blow, that says farewell to carnality and worldliness with utter Broadway razzamatazz, and a gangster’s girlfriend showing off her underwear doing high kicks) you know you’re in the presence of ribaldry.

But by the same token when you hear expressions of longing like I Get A Kick Out of You and All Through the Night, you cannot be blind to the fact that the lyricist knew a thing or two about the emotional side of love as well. He knew about being in love when the object of your affections doesn’t reciprocate – which is in fact the situation limned by I Get A Kick Out of You. Indeed, that was the one obvious thing I shared with Cole Porter, after eliminating, for instance, being grownup, or gay but stuck in a straight marriage, the way he was. And the contrast was more marked with Reno Sweeney, the character singing the song (Ethel Merman in the original, Eileen Rodgers in the revival). Unlike Reno, I was a) male, b) young, c) unfamiliar with drugs and alcohol, d) not accustomed to flying airplanes, and e) never known to go “out on a quiet spree,” whatever that exactly means. (In Porter’s case it probably meant trolling the louche bars of the Left Bank for the relief of easy male companionship.) So there was a lot I couldn’t identify with in the song.

But the heart of it was all me. Like Reno and Cole, I understood that the secret obsession one might entertain for the object of one’s affections would make every other amusement pale a little. I don’t think that I would have described going to movies, playing board games, or hanging with my friends (my competing satisfactions) as “my idea of nothing to do,” as Reno phrases it, but there was no question that the pinnacle of my emotions right then was reached when I was talking on the phone with Patricia. This song spoke powerfully to that[5] – and the distinctions between me and the writer, and/or me and the singer, were just static, just statistical error.

And so I listened a lot to that album. It was more than getting a fix of ribaldry and sentiment. It contributed to my musical ear too. The musicals whose records I’d grown up with to this point had all had full orchestras. Anything Goes featured a charming but distinctly pared-back ensemble, in which you can hear every instrument clearly, and every instrument counts (it has to). I was in love with the sound of that pit band. I must have listened to the overture a dozen times just to hear its sonorities. And when it came to I Get a Kick, somehow the trumpet’s melancholy in that song made it for me more than Rodgers’ voice.

That was the beginning and end of my Cole Porter experiences until the Rock Era, when Porter would come back in a different setting altogether. But that’s a later story.

The tale of Patricia took a while to wind down too, but I can summarize. Matters reached their crisis the following year, the Saturday after Kennedy’s assassination. I was walking along with her and, in my mourning and my longing, tried to put my arm around her. The reaction I got made it clear that this was not at all a direction she’d ever thought we might go. She more or less fled. And that ended up being more or less that.

I get a kick, Though it’s plain to see You obviously don’t adore me.Amen.

[1]. It’s hard to convey now – when everyone has a cell and can talk across the country for the same price as across the street, and can e-mail, instant message, post on Facebook, or tweet – how the limited number of party-line landline phones in one’s home, phones that one’s parents could eavesdrop upon, and the barrier posed by Long Distance rates loomed over the early adolescent effort to have confidential talks.

[2]. For a little background on the Orpheum theater, see here.

[3]. Quoted in Curtis F. Brown’s excellent liner notes of the recording of the 1962 revival discussed here.

[4]. Well, almost. The reference to cocaine (“I know that if / I took even one sniff / It would bore me terrif-/ ically too”) had to be changed for the movies and probably doesn’t get used in high school productions. But in those more innocent (or is it sophisticated?) times, cocaine was viewed more neutrally by popular culture, as an intoxicant of a legitimacy on a par at least with that of alcohol. In 1934, when these words were first sung, cocaine was regulated in the United States as a narcotic (incorrectly, since it is actually a stimulant), which meant that it could be possessed and used with a license. And apparently there was little or no enforcement activity directed at it until it was classified as a Controlled Substance in 1970. Meanwhile, and by way of significant comparison, Prohibition has just been repealed two years earlier. The unjustified banning of alcohol doubtless diminished the respect Porter and his contemporaries would have felt for attempts to stigmatize and illegalize cocaine. Whether their views about either alcohol or cocaine were right or wrong is beyond the scope of this essay.

[5] After Frank Sinatra, most singers have jazzed up the song. This is a perfectly legitimate use of the material, but not the best. It was designed to be sung slowly and longingly. Don’t be deceived by cheap imitations.

Copyright (c) Jack L. B. Gohn