Previews of Love

Theme Songs Page | Previous Theme Song | Next Theme Song

Previews of Love

Do It Again, sung by Judy Garland 1961, encountered 1962?

Lazy Afternoon, sung by Marlene Dietrich 1954, encountered 1962?

Strange how potent cheap music is, Noel Coward advises, in an understatement.[1] Such power isn’t merely over our emotions; it also informs our thinking. That’s particularly true if we happen to be just entering adolescence, before we’ve had any meaningful seasoning of reality to counter or at least temper what the cheap songs tell us. I think Plato wanted to keep the poets away from youth for just that reason: the notion that they would mislead the kids.[2] Poets misleading kids I don’t know about; songwriters and singers, definitely. But being misled that way is part of any fully-lived adolescence, if you ask me. With apologies to Plato, I’d rather be deceived and misled in my impressionable youth than do without my cheap music. In fact, being deceived and misled was an enjoyable part of growing up also. And I’ll bet you found it that way too, gentle reader.

And so we come to a couple of numbers that misled me a bit as I was beginning to think more seriously about girls. I was then about thirteen. I had all these, uh, feelings, and was trying to match up some kind of plausible scenario to them. Enter two popular chanteuses to serve up suggestions: Marlene Dietrich and Judy Garland.

Bit of background: Dietrich had been an immense favorite during the War, but I think by the early 60s she was becoming a bit vieu jeux with the public at large, though with people of my parents’ generation, then nearing their fifties, there was great loyalty. I sensed that in buying all Dietrich’s records, my parents were clinging to an increasingly old-fashioned taste, which meant that I felt a little bit sophisticated sharing it. (I was just a year or so too young to be tempted to be embarrassed because I liked something out of date.)

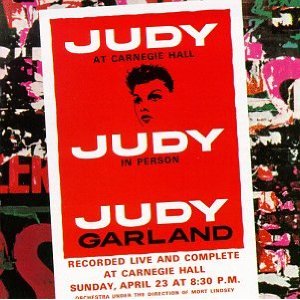

Garland was having a different career trajectory, going up and down all the time, but mainly up. And she had just at this point enjoyed the biggest night of her career, her big concert at Carnegie Hall in 1961. Everyone loved the double album that came out of that. My frenemy Paul, fiercely competitive with everyone, had the album before anyone, and knew all the songs by heart. I mention this because Paul was the type to have a sense what was acceptable and what was out among us young teens, and was not the type to have publicly indulged in a taste that was unacceptable.[3] The album charted for 73 weeks on the Billboard chart, including 13 at No. 1. So responding to that album was simply a different matter from responding to Dietrich’s – even though neither of these ladies was prime teen-listener material (at their respective times of recording the songs I want to talk about Garland was 38, Dietrich 53 – and Dietrich was in her sixties at this point).

At this point, my mom and stepdad and I would spend a lot of time socializing with other faculty families. For whatever reason, I tended to be the oldest kid a lot of the time, and so I tended also to be the one up latest after my younger peers had been put to bed, which meant that I spent the occasional evening in houses with grownups doing their thing (drinking, smoking, arguing, laughing) while I was sometimes the only one doing my thing. And the problem sometimes was that I wasn’t exactly clear what my thing was.

But somehow my thing, especially at late hours when I was the only youngster awake in the house, came to include thinking about girls. Not so much any specific one, although that would start happening soon enough. But right at this point, I was just trying to imagine what it would be like to – well, there isn’t a good word for it. Sex (of which I’d understood the mechanics already for a few years) was definitely not what I was trying to imagine. As a good Catholic schoolboy, I knew that that kind of thing wasn’t on the program until I got married. I guess the best way to say it was I was trying to visualize romance.

Judy gave me one idea.

You really shouldn’t have done it, You hadn’t any right. I really shouldn’t have let you kiss me. And although it was wrong, I never was strong. So as long as you’ve begun it, And you know you shouldn’t have done it, Oh, do it again. I may cry no, no, no, no, no, but do it again. My lips just ache to have you take The kiss that’s waiting for you. You know if you do you won’t regret it. Come and get it.The way Judy sang Do It Again in that Carnegie Hall presentation told me a lot, maybe not all of it right, about female longing. But it made conceivable, perhaps for the first time, that women might like kissing, even if they didn’t admit it right off the bat. Overcoming their reluctance sounded like fun, so long as the reluctance was only – what? – not feigned, but provisional and temporary, like Judy’s. I never visualized forcing a kiss from someone who really didn’t want to. But that was the problem in a nutshell: how could you tell before you tried? And there was a secondary problem: how were you going to deal with the embarrassment if you discovered they really didn’t want to? (A dilemma that I believe continues to haunt nice young men through the generations.)

It’s not just the words, of course. Judy makes her voice soft and naive and virginal. Had Ethel Merman sung the same thing, it might have rung a bell or two with adult listeners, but not with a 13-year old. Thank goodness, too, I had the old LP, and not the CD reissue, which includes about 1:20 of monologue after the applause dies down, all about how Judy might have a cold, having perhaps “picked up an old fungi in Atlanta.” And all of the sweetness is gone from her now-New York-accented voice, a cultivated but recognizably Gothamite accent like my father’s and my aunt’s – way too grownup. What my young adult son now calls a buzzkill. My early adolescent fantasies might not have been the same.

The funny thing about that lyric is that the key phrase, “do it again,” reportedly originally came into the compositional process when lyricist Buddy DeSylva was urging on composer George Gershwin to repeat a musical phrase. I guess it’s part of the genius of songwriting to transmute simple directions into expressions of longing.

Well, in my fantasies, somehow I was going to get over that obstacle of finding the girl who actually wanted to kiss back – how, I wasn’t certain, but it was going to happen. Then what? That was where Marlene came in with Lazy Afternoon. She presented me a plausible fantasy about what the blissful communion of two lovers might be all about. I should hasten to add that it was about the only completely graspable thing on the album where I encountered it: Marlene Dietrich at the Café de Paris (1954).

This vinyl platter was a mass of confusing semiotics (a word I learned much later in life, of course) that it was going to take me years to work my way through, but I sensed I didn’t get the half of what was going on.[4] One of the few songs I thought I really understood was Lazy Afternoon. It suggested what I and the girl might do once we discovered we really, really liked each other. We could walk out to the countryside together and sit very, very still, and let nothing happen, and it would be incredibly intimate:

It’s a lazy afternoon And the beetle bugs are zooming And the tulip trees are blooming And there’s not another human in view but us two It’s a lazy afternoon And the farmer leaves his reaping In the meadow cows are sleeping And the speckled trouts stop leaping upstream as we dream A far pink cloud hangs over a hill Unfolding like a rose If you hold my hand and sit real still You can hear the grass as it grows It’s a hazy afternoon And I know a place that’s quiet except for daisies running riot And there’s no one passing by it to see Come spend this lazy afternoon with meThe orchestration is simple, alive with shimmering strings that suggest a sultry afternoon. It’s all very, for Dietrich, unambiguous. In recent years, the song has been recorded by everybody (AllMusic.com lists 500 recordings including Barbra Streisand, Vanessa Williams, and Wynton Marsalis), but Dietrich’s was almost certainly the first,[5] and there still weren’t many by 1962. So this came at me as a breathtaking first.

It provided me with a plausible picture in my work-in-progress fantasies of what might happen after the Do It Again kisses. In Ann Arbor of 1962, you could still walk from the center of town to real farms (much harder now). And with my parents, I would sometimes be driven to places that were just a little further out that were so unpopulated you could truly be alone. I’d slip away from the grownups, and go for a long walk in deserted fields and by deserted ponds, and think about what bliss it would be to have someone who loved me to share it all with. That sounded pretty good to me.

Strange how potent cheap music is!

[1]. Private Lives, Act I (1930).

[2]. Glance around Book II of The Republic.

[3]. De mortuis nil nisi bonum. Paul’s life was full of vagaries, and he died of a very bad disease. It’s startling how little animus one can feel about a contemporary in light of such facts. I’m getting too old, regrettably, to hold good grudges any more.

[4]. We start with the cover, Marlene with her face probably plastic-surgerized and definitely airbrushed to such a ridiculous extent one stares at its featureless smoothness in wonder. She is swathed in white furs against a backdrop of Tiffany blue, coming across like some vision of young perfection, when everyone (even I) understood she was getting on for ancient. On the back she is pictured in a diaphanous gown that looks as if she’s naked, yet one knows she isn’t. And again, no woman her age (and few of any age) has such a perfect-seeming body.

She’s introduced in couplets by Noel Coward (warning: not on the .mp3 download issued in 2010) in a paean to her sex appeal. A sample: “For female allure, whether pure or impure, has seldom reported a failure.” Well, probably it reported a failure with nearly-out gay Noel Coward. And what about the fact that Dietrich was fairly lesbian herself? Or the liner note by Jean Cocteau, also gay? A sample from him: “Marlene Dietrich!… Your name, at first the sound of a caress, becomes the crack of a whip. When you wear feathers, and furs, and plumes, you wear them as the birds and animals wear them, as though they belong to your body.” Coupling that saluation with the white ermine adorning Marlene on the cover, would I be the only one hearing echoes of Sacher-Masoch? No, actually not: in another liner note Kenneth Tynan, a known S/M fan, made it explicit, calling Marlene’s persona as she presented this performance “the Venus in furs.”

Moving on to the music, there’s the odd blending of German accent with a Western song from Destry Rides Again, the sort of playing with men and kicking them to the curb stuff that she patented from The Blue Angel, and just layers of irony and self-conscious showmanship covering everything she did.

It’s all good, of course. Nothing at all wrong with polymorphous themes running just under the surface. Just confusing as hell to a 13-year old.

[5]. The performance from which the recording was taken occurred June 21, 1954. The song apparently came from the musical, The Golden Apple, lyrics by John Latouche, music by Jerome Moross, which had premiered in March of the same year to great acclaim but what turned out to be a limited run. Dietrich must have snapped it up as soon as she or her people heard it. When she announces some of the songs, there’s a big cheer from the audience that tells us the song was familiar to them. With this one, there’s no such reaction. While the musical was still playing on Broadway on the recording date, the Café de Paris, where Dietrich was singing, was in London. That might account for some of the unfamiliarity, but surely the recency of the song had more to do with it.

Copyright (c) Jack L. B. Gohn