Religious Writings Page | Previous Religious Writing | Next Religious Writing

The Book of Job: Little Things and Great Ones

Delivered as a homily during an Easter Vigil service 2016 at St. Vincent de Paul Church, Baltimore

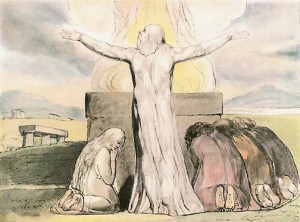

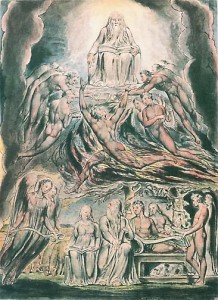

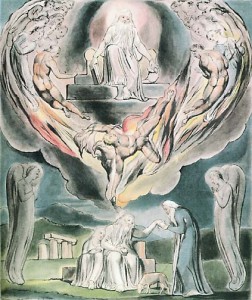

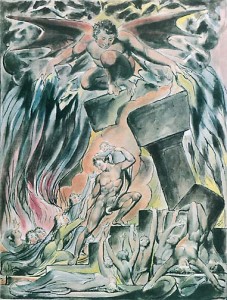

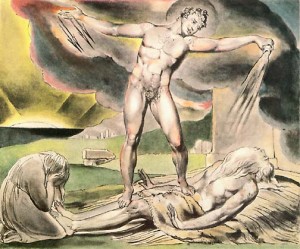

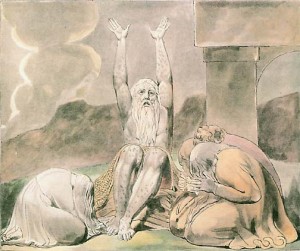

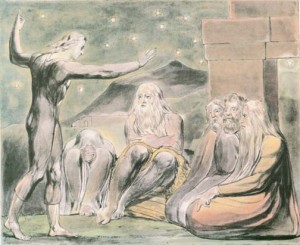

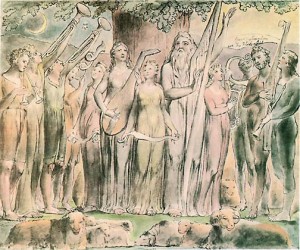

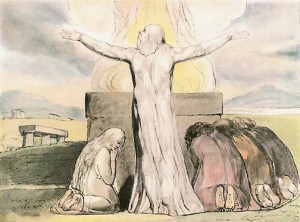

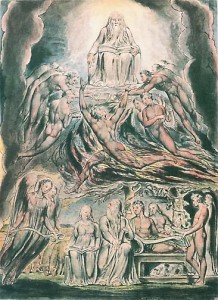

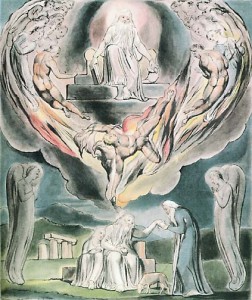

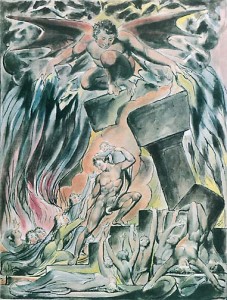

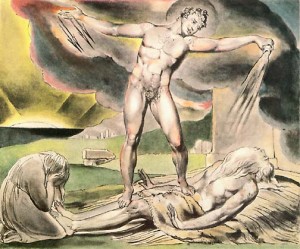

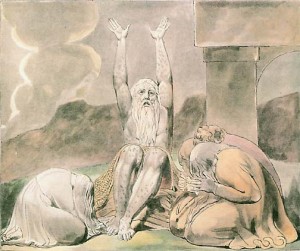

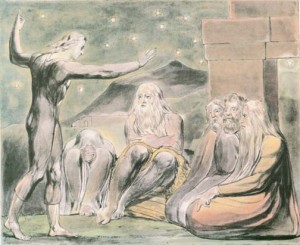

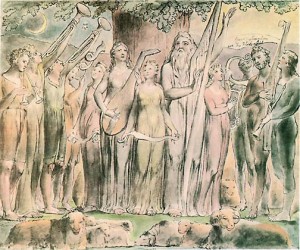

(This talk was preceded by a playing of Song of Job, by Jim Roberts and Andy Kulberg, performed by Seatrain (1970). See it here. It was illustrated with some of William Blake’s illustrations to the Book of Job, reproduced in the margins below.)

Most of us know the Book of Job, to the extent we know it at all, as a straightforward U-shaped narrative, that is a story of how things start out one way, change, and then come back to being the way they were when they started. The song you’ve just heard strips the book down to give you just that U-shaped narrative. In it, Job, a pious man, starts out healthy, wealthy and wise; then everything goes to hell because God is testing him; then Job passes the test, and so God sees to it that Job ends up healthy, wealthy and wise again. And that description is true as far as it goes, but it doesn’t go very far.

Between the Bookends

As soon as you start to look more closely at the book, it gets more complicated. Structurally, it is less like a U and more like a bookshelf with the books held up by bookends. Job starts out with what seems to be the beginning of a simple prose folktale and ends with the prose conclusion of that tale. The folktale takes up Chapters 1 and 2, and then resumes mid-way through the very last chapter, Chapter 42. The 39+ chapters in between them are poetry, of a very high order and of considerable philosophical complexity, subdivided into many parts. The song you’ve just heard covers that material in only a few lines. But they are really the heart of the Book; the folktale gives it context, the way bookends give the books on a shelf shape.

As soon as you start to look more closely at the book, it gets more complicated. Structurally, it is less like a U and more like a bookshelf with the books held up by bookends. Job starts out with what seems to be the beginning of a simple prose folktale and ends with the prose conclusion of that tale. The folktale takes up Chapters 1 and 2, and then resumes mid-way through the very last chapter, Chapter 42. The 39+ chapters in between them are poetry, of a very high order and of considerable philosophical complexity, subdivided into many parts. The song you’ve just heard covers that material in only a few lines. But they are really the heart of the Book; the folktale gives it context, the way bookends give the books on a shelf shape.

How did the book get this structure? Clearly to most scholars, the folktale material at the beginning and end is a much older text, and it was sliced in half by revisers, and all that poetical discourse inserted in the middle. And it makes sense to me.

How did the book get this structure? Clearly to most scholars, the folktale material at the beginning and end is a much older text, and it was sliced in half by revisers, and all that poetical discourse inserted in the middle. And it makes sense to me.

Now the bookend analogy does break down in one critical way. It doesn’t describe well a typical modern reaction to Job. Most of the time, with a modern bookcase, we obviously prefer reading the books to reading the bookends. But with Job, to the modern imagination, the folktale part at the ends, the bookend part, if you will, goes down a lot easier than the philosophical disputes in the middle. We much prefer folktales to philosophical arguments, even when the arguments are well done and quite poetic. Still, we can be quite sure the ancient authors who assembled the book weren’t crazy; they must have thought something was awfully valuable in all the discourse and poetry, or they wouldn’t have turned a simple tale into a mini-epic to make room for it.

So why did they do it? What was so great about the discourse and the poetry? And what use and relevance do the discourse and the poetry have for us?

So why did they do it? What was so great about the discourse and the poetry? And what use and relevance do the discourse and the poetry have for us?

To answer those questions, of course, we have to look at what happens there. There are six speakers over those many chapters. There are Job, three friends of Job named Eliphaz, Zophar, and Bildad, and a young man named Elihu who thinks he knows better than his elders, and spouts off for awhile. And then God bats last.

Challenging God

Job is remarkably consistent in his approach to his misfortunes, though he certainly grows in volume and intensity as he goes along. He hates his life, he says – which is quite believable given that his wealth has been carried away, his children have died, and he is covered with unsightly and painful boils. He hates his life, and he wishes he were dead or had never been born in the first place. He does not understand why God would do this to him. He has led an exemplary life. And if he has been sinful in any regard, that is merely consistent with the way God made him. God is supposed to be just, and if He deviates from justice, he’s supposed to be merciful. Where are God’s justice or mercy in the way Job has been treated? In effect, Job challenges God.

Job is remarkably consistent in his approach to his misfortunes, though he certainly grows in volume and intensity as he goes along. He hates his life, he says – which is quite believable given that his wealth has been carried away, his children have died, and he is covered with unsightly and painful boils. He hates his life, and he wishes he were dead or had never been born in the first place. He does not understand why God would do this to him. He has led an exemplary life. And if he has been sinful in any regard, that is merely consistent with the way God made him. God is supposed to be just, and if He deviates from justice, he’s supposed to be merciful. Where are God’s justice or mercy in the way Job has been treated? In effect, Job challenges God.

Eliphaz, Zophar, Bildad and Elihu all, in one way or another, refuse to accept Job’s premise. They reason that if Job has been afflicted, Job must have sinned, because God cannot be unjust. In contemporary terms, they do not accept that bad things may happen to good people. If bad things happened to Job, then, by this logic, Job must be bad people.

Now, we can agree that the three friends and Elihu are certainly quite wrong in their premise; everyone knows that good things regularly happen to bad people and bad things regularly happen to good people. And in the end we all die, good or bad. As Stephen Sondheim memorably summarized it in a lyric: “It’s called flowers wilt,/ It’s called apples rot,/ It’s called thieves get rich and saints get shot,/ It’s called God don’t answer prayers a lot.”

Unthinkable

But you can see why the friends and Elihu would have struggled so hard not to recognize this: the implications of “God don’t answer prayers a lot” were close to unthinkable. For the authors of the Book of Job and their audience, there was no afterlife, no do-over in which God could set right any misfortune befalling good people, or take back any ill-gotten gains accruing to the thieves who got rich. In short, there was no reliable justice, and no reliable mercy. What would that tell us about God?

But you can see why the friends and Elihu would have struggled so hard not to recognize this: the implications of “God don’t answer prayers a lot” were close to unthinkable. For the authors of the Book of Job and their audience, there was no afterlife, no do-over in which God could set right any misfortune befalling good people, or take back any ill-gotten gains accruing to the thieves who got rich. In short, there was no reliable justice, and no reliable mercy. What would that tell us about God?

We Christians do believe that there is a do-over, of course; that is one of the most consistent things in Jesus’ message. To be sure, Jesus never describes it as a do-over – rather, in Jesus’ description our lives to come are the culmination of our existences, not a repetition nor, on God’s part, a chance to rectify any mistakes. But there is an opportunity to execute fully God’s justice and mercy which, if we’re honest with ourselves, we cannot plausibly claim are fully executed in this life.

But even if we believe this, it doesn’t clear up the whole problem. Not at all.

And actually we can see that in how we react to the ending of the story. We are told that Job is restored to twice his former wealth, and apparently he sires a new family to replace the one God struck down. And “he saw his children, his grandchildren, and even his great-grandchildren. Then Job died, old and full of years.” This is the general Biblical formula for “and they all lived happily ever after.” But it is also specific; according to the Book of Job, the hero gets a new family, and he’s just as happy with them as he was with his old one, and God has now, implicitly, made full restitution.

A Barbaric Restitution

Well, that’s nice. But in the meantime, a whole bunch of innocent members of Job’s first family were slaughtered just so God could deprive Job of their company. To be fair, they’re not really people. This is a folktale, and they’re not characters in it, just counters quantifying Job’s well-being as a man and a chieftain. We are told the number of his sheep, camels, oxen, and sons and daughters. They’re all in the same category. It may reflect the barbarity of the civilization that gave rise to this story that, while Job may feel their loss as a loss to him, their own dignity and their value to themselves does not enter into the equation.

Well, that’s nice. But in the meantime, a whole bunch of innocent members of Job’s first family were slaughtered just so God could deprive Job of their company. To be fair, they’re not really people. This is a folktale, and they’re not characters in it, just counters quantifying Job’s well-being as a man and a chieftain. We are told the number of his sheep, camels, oxen, and sons and daughters. They’re all in the same category. It may reflect the barbarity of the civilization that gave rise to this story that, while Job may feel their loss as a loss to him, their own dignity and their value to themselves does not enter into the equation.

And when we hear that God has taken these irreplaceable human lives and then, by bringing forth other human lives, thinks He’s evened the score, well, that just tells us that the God of the Book of Job shares some of the barbaric values of this barbaric culture. And it certainly does not make a modern audience feel all warm and fuzzy about God.

Especially not when we remember why, according to the story – at least as told in the bookends, in the folktale – God has stricken down Job’s first family and his first fortune to begin with: to win what at first blush looks like a bar bet with Satan.

“Satanic” Quality Control

Now, it’s not quite as scandalous as one might think in one respect. This Satan is not the fallen angel of Milton’s Paradise Lost; he is not what we call the Devil in popular culture. Scholars think the Satan of the Book of Job is more like God’s quality control inspector. God thinks Job is a fine piece of spiritual work; Satan is not convinced, and suggests that God needs to make sure. So it’s not so much God and Satan gambling, for the sheer fun of it; more like running tests on a sample that just came off the assembly line just to be absolutely sure it is marketable.

Now, it’s not quite as scandalous as one might think in one respect. This Satan is not the fallen angel of Milton’s Paradise Lost; he is not what we call the Devil in popular culture. Scholars think the Satan of the Book of Job is more like God’s quality control inspector. God thinks Job is a fine piece of spiritual work; Satan is not convinced, and suggests that God needs to make sure. So it’s not so much God and Satan gambling, for the sheer fun of it; more like running tests on a sample that just came off the assembly line just to be absolutely sure it is marketable.

So: not as scandalous, but still scandalous. It’s still not right that Job be put through excruciating losses and pain just to confirm he’s a great guy and a faithful one, even if we decline to weigh the suffering of his family members in the balance at all.

Small wonder that critic Harold Bloom felt that the ending was not original, but was stuck in by a pious rabbinic fool. It seems to trivialize Job’s suffering, making of it just a temporary deprivation of the riches in a very rich life.

And maybe we will conclude that the original version of the story, the U-shaped tale of a rich man humbled and then exalted again makes God look pretty bad. Though I’d ask you to withhold judgment for a few minutes.

God’s Answer

The poet or poets who took over and wrote the long middle of the Book have a much different approach and a different answer to Job’s challenge. I’ve told you already in essence what Job says and what the friends and Elihu say. But I also mentioned that God bats last, and I haven’t yet adverted to what God says. Let me just read you a little to give you the flavor of it:

The poet or poets who took over and wrote the long middle of the Book have a much different approach and a different answer to Job’s challenge. I’ve told you already in essence what Job says and what the friends and Elihu say. But I also mentioned that God bats last, and I haven’t yet adverted to what God says. Let me just read you a little to give you the flavor of it:

1 Then the LORD addressed Job out of the storm and said:

2 Who is this that obscures divine plans with words of ignorance?

3 Gird up your loins now, like a man; I will question you, and you tell me the answers!

4 Where were you when I founded the earth? Tell me, if you have understanding.

5 Who determined its size; do you know? Who stretched out the measuring line for it?

6 Into what were its pedestals sunk, and who laid the cornerstone,

7 While the morning stars sang in chorus and all the sons of God shouted for joy?

8 And who shut within doors the sea, when it burst forth from the womb;

9 When I made the clouds its garment and thick darkness its swaddling bands?

10 When I set limits for it and fastened the bar of its door,

11 And said: Thus far shall you come but no farther, and here shall your proud waves be stilled!

11 And said: Thus far shall you come but no farther, and here shall your proud waves be stilled!

12 Have you ever in your lifetime commanded the morning and shown the dawn its place

13 For taking hold of the ends of the earth, till the wicked are shaken from its surface?

14 The earth is changed as is clay by the seal, and dyed as though it were a garment;

15 But from the wicked the light is withheld, and the arm of pride is shattered.

16 Have you entered into the sources of the sea, or walked about in the depths of the abyss?

17 Have the gates of death been shown to you, or have you seen the gates of darkness?

18 Have you comprehended the breadth of the earth? Tell me, if you know all:

19 Which is the way to the dwelling place of light, and where is the abode of darkness,

20 That you may take them to their boundaries and set them on their homeward paths?

21 You know, because you were born before them, and the number of your years is great!

God goes on to discuss the astonishing variety of animals He has created, and dissertates for some time about the warhorse, Behemoth (the hippopotamus), and Leviathan (the crocodile). Creation as extolled by God, is huge and intricate and powerful and full of wonderful things.

God goes on to discuss the astonishing variety of animals He has created, and dissertates for some time about the warhorse, Behemoth (the hippopotamus), and Leviathan (the crocodile). Creation as extolled by God, is huge and intricate and powerful and full of wonderful things.

Good Enough for Job

That answer is certainly enough for Job. He responds as follows:

1 Then Job answered the LORD and said:

2 I know that you can do all things, and that no purpose of yours can be hindered.

3 I have dealt with great things that I do not understand; things too wonderful for me, which I cannot know.

5 I had heard of you by word of mouth, but now my eye has seen you.

6 Therefore I disown what I have said, and repent in dust and ashes.

Now God’s response to Job is not a direct answer. God says nothing about Job’s entitlement to justice or his petition at least for mercy or, failing that, for oblivion. But there is a clear implied answer: God’s plan is so vast, so mighty, so beyond human comprehension, that the way everything relates to Job’s little part in it is bound to be beyond human comprehension as well.

Now God’s response to Job is not a direct answer. God says nothing about Job’s entitlement to justice or his petition at least for mercy or, failing that, for oblivion. But there is a clear implied answer: God’s plan is so vast, so mighty, so beyond human comprehension, that the way everything relates to Job’s little part in it is bound to be beyond human comprehension as well.

Not Good Enough for Us

This answer does not fall well on modern ears.

We get it that we don’t know everything. In fact, thanks to modern physics and cosmology we have a much clearer picture than the ancients did how unimaginably vast our cosmos is, and how many things within it, some of them quite fundamental, are unknown and likely to remain unknowable to us. Still, justice and mercy are things we think we do understand pretty well. We get basic fairness, much more even than did the civilization that begat the Book of Job. We’ve had Magna Carta and the Declaration of Independence and the Bill of Rights and the Emancipation Proclamation and the Geneva Accords and the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. We know we haven’t learned everything there is to know about justice and mercy, but we think we’re on the right track – and what God did to Job looks as if it’s on the wrong track.

And that matters. It matters tremendously because, to a religious mind, justice and mercy are tied up with the divine nature. They have meaning, they make a demand on us, precisely because they emanate from God. If they were not of divine origin, they might make no such demand on us, and a God who was not a God of justice and mercy would certainly not be the God we have thought we were worshiping, either.

And yet: the divine justice and mercy cannot be directed merely by what we see and understand. We do not and cannot see enough of the picture. And it is presumptuous of us to act as if we did.

God’s Fairness Not Ours

A message of the Book of Job, then, is that God is not just or fair in the limited way we understand those things. God’s covenant with us is that He will be our God and we shall be His people; there is nothing in there promising no crucifixions, as Jesus could tell us.

But the message goes further; the Book of Job says that this apparently intolerable state of affairs is still okay. God has bigger things going, a vast universe of which we are an infinitesimal part, a grand design we cannot hope to comprehend, and in this grand design God will do things that we cannot with our limited perspectives accept as fair – but it will be all right. Thieves will get rich and saints will get shot – and it will be all right.

We Christians are in the midst of a celebration of exactly that mystery. What happened to Jesus was a scandal. From our human perspective, nothing could be more unfair of the Father than to hand to Jesus the cup of the death Jesus had to die. But there was a bigger design at work. It was going to be all right, and that injustice, that scandal of the Cross, was at the heart of the process whereby it became all right.

Conversely, if Jesus had turned away, and insisted on fair treatment, if Jesus had not embraced what from an ordinary human perspective looked like meaningless suffering, it would not have been all right.

Joyous Days

And there’s one other lesson the Book of Job would teach: that at the end there is gladness. “Job lived joyous days,” the song tells us. “He saw his children, his grandchildren, and even his great-grandchildren,” the Book tells us. Maybe the gladness is not in this life, but there will be gladness. That too is part of the grand design. That gladness, incomprehensible and unfathomable, is almost as much of an affront to our way of thinking as was the pain that had preceded it.

Definitely an affront to critic Harold Bloom, whom I cited earlier, for the view that the ending was an afterthought stuck on by a stupid rabbi to make a scandalous story palatable. Both as a matter of textual history and as a matter of the story being told, Harold Bloom was wrong. According to the majority of scholars, the ending was not an afterthought. It was the original ending of the story, the oldest part, carrying the accumulated wisdom of the culture that had produced it. There will be suffering, those ancients tell us, but it is a little thing. There will also be gladness, and it is a big thing, the big thing. It will not be fully comprehensible to us why this is right, but it is right, and it is coming our way. And the best way to await it is with faith and with patience: The Patience of Job.

One afterthought: Just because we cannot comprehend divine justice and mercy does not let us off the hook on our own obligation to act justly and mercifully as we understand these things – though it may require us to be constantly questioning our assumptions as to what these concepts mean or demand. That’s a big subject for another time, but it has to be mentioned in passing.

Copyright (c) Jack L. B. Gohn

Religious Writings Page | Previous Religious Writing | Next Religious Writing