God’s Extravagant Creation

Edited Version of Remarks Delivered at St. Vincent de Paul Church’s Easter Vigil 2017

Buckle up! In the next few minutes we are going to cover an immense amount of distance and time, and think about some challenging things, and I aim to make the ride a little bumpy. All set?

Going back over the years, this may the fourth time I’ve talked at this service about the opening stories of Genesis. Recently I’ve focused on the hard lessons of Chapters 2 and 3 about morality and mortality. But to get to them, I kind of skipped over the two utterly enthralling and fascinating creation stories in Chapters 1 and 2. We just heard the first of those stories, about the dawn of everything.

Unapologetically Anthropocentric

Genesis 1 and 2 tell us about God fashioning everything, and setting the table for us, creating a world with the fundamental requirements for us to exist: earth, sky, sea, night and day, plants, animals – and us ourselves. It is a fundamentally anthropocentric story, in which mankind is presented unapologetically as the crown of creation, and in it all that is created is stated to be for man’s benefit.

There is another theme in the creation myths of Genesis: the wonder of it all. When God keeps marveling how good it all is, it’s an invitation to us to marvel as well. And it’s even easier for us than for the ancients who came up with this story; they had no remote idea how wondrous it really all was. We have a better one.

This evening, I want to compare and contrast the ancients’ ideas with those of modern scientists about the same things – as best I can. Now, most of you know that I’m no scientist. That said, I do read a lot. And one thing I can tell you with confidence is that what we think we know on this subject is dwarfed by what we can be quite certain we don’t know. The most informed people know just enough, as the saying goes, to be dangerous. But here we go!

Still the Appropriate Reaction

Modern scientists, when they try to reconstruct the way everything came about, are more resistant to the notion of everything being assembled with our arrival in mind. Yet it is hard to put the scientific story together without seeing that human-centered story arc in there. I’m not saying it’s logically compelled, but in a mysterious way it seems to make sense, given our limited information.

And marveling at this insanely huge creation is still the appropriate reaction.

So let’s look at the standard modern version and see what echoes it evokes next to Genesis. I will start out by saying that whether there was anything before the Big Bang, the explosion that kicked off our universe – whether that is even a meaningful question, is up in the air as far as scientists are concerned. I wish I could do justice here to the richness of the concepts involved, but I lack the time and the scientific knowledge or rigor. I’ll simply say that if you look at the red shift, the changes in spectrum that tell us where the stars are going from and to and how fast, and if you decode the cosmic rays that are part of the background radiation in space, you cannot avoid concluding that it all started in one spot.

Before-ness in the Singularity

And by all I mean all: all matter and all space as well. But if it really was in one spot, then it must have been a spot of infinitesimal size and nearly infinite mass and heat and energy. The trouble is, if you posit that, then at that spot, all the laws of physics, both conventional and quantum physics, break down, among them the laws governing time. There basically isn’t supposed to be time in a singularity like that.

So what do we do with the notion that our universe may not have had any time when it started? What does that do to the question of what may have existed before it? Before-ness is a quality that only makes sense in the context of time. There are cosmologists who get around the problem by saying that in that context time curves. I guess that suggests that time slingshots around that singularity the way a spacecraft can sling around the gravitational field of a planet and come back. Otherwise put, perhaps our universe has always been here, because in curved time there would be no such thing as a beginning.

But wait! If that were true, what room would there be for a God the Creator?

Sorry, Aquinas!

Whatever Thomas Aquinas, with his emphasis on God’s role as the source of everything, might have said, the author of Genesis would not have seen the problem. Remember, in Genesis, the Creation is not quite the origin of the world. By the time God gets to work in the story’s first couple of sentences, there is already an ocean and a formless wasteland that, for all the story tells us, could have existed from all time. In Genesis, God’s creativity seems to work on materials that already exist.

Or course, if you could interrogate the author of Genesis, you might find that he or she attributed the ocean and the wasteland to an earlier act of God’s creation. Who knows? If you need to see a God as in some sense prior to the emergence of anything, though, then I need to mention what some quantum physicists think: that matter and energy bubble in and out of existence all the time, and that the origins of the singularity that existed before the Big Bang may have lain in this kind of spontaneous self-generation. There is also a theory that ours is just one of an infinity of universes bubbling up out of nothing. Again, none of this rules out divine agency. A natural order in which universes bubble up out of nothing cries out – to our human minds, at least – for a cause. Can a natural order create itself, even one in which things spontaneously generate? That thought just seems wrong.

In any case, time and our universe did get started. Most scientists think now that the start was the explosion we call the Big Bang about 13.6 billion years ago. And the story from there to here – well, let’s just say that it sure lends itself to seeing an intentionality at the center. A lot had to happen before there could be a world for us.

What Had to Happen

Let’s break it down some. First, much is supposed to have happened in the first milliseconds. One of the first changes, scientists think, was the predominance of only three dimensions among the ten or eleven our mathematics seems to show must exist. The remaining dimensions are thought to have curled up tight so that they are not major players. If they had not done that, apparently gravity wouldn’t have worked right. Don’t ask me to explain what I just said, because I can’t, but I think there’s a lot of scientific consensus behind it.

Just like the void of which Genesis speaks, gradually taking form, scientists envision the way that our mostly three-dimensional universe took form from a plasma – hot non-molecular atomic particles, uniformly distributed throughout the cosmos. (I can’t show you a picture, because there wouldn’t have been any light emitted from that heat.)

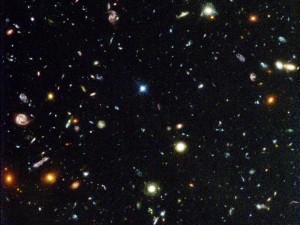

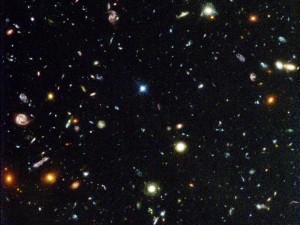

Then, little bits of plasma bumped up against each other and stayed together, bound by basic physical forces. Gas atoms formed. These atoms kept bumping up against other ones, and congregated, so the clouds of gas grew and grew. And because of the physical laws dictating what happens when matter aggregates, they got hot and started the reactions that turned these balls of gas into stars. Billions and billions of stars. And light again. At this point we’re maybe a hundred million years out from the Big Bang. (Here’s an actual photo from the Hubble of what the universe looked like then.)

Also important was the formation of the first black holes. Nowadays they come from collapsed supernovas; perhaps initially they were fragments of the singularity. In any case, they did a vital job of pulling stars together into formations we call galaxies. In those formations, stars could collaborate more closely on joint projects like forming elements.

Life in a Balloon

Meanwhile space itself was growing, and apparently continues to do so. Here’s something to wrap your mind around: if we have any descendants ten billion years from now, they’ll look up and they won’t see too many other galaxies besides our Milky Way, despite the fact that there are billions of galaxies. Why? Because most of the other galaxies will have moved so far away from us and so quickly that the light from them will never reach us.

How is that possible? We’re told that nothing can move faster than light. So however fast these other galaxies are moving, surely they can’t outrun the light they are shining on us. And that would be true, if space itself, including the space between us and other galaxies, weren’t expanding. We don’t understand what space is, but the best comparison for this purpose is to a balloon. Whatever space is, it has been or is being pumped into this balloon so rapidly that almost everything in that balloon is being separated from everything else at a speed that exceeds the speed of light.

For the time being at least, we can see a lot of galaxies. And right now, we can see about 46 billion light years in any direction. In other words, we can look around within a sphere of double that diameter, about 91 billion light years wide. It all looks like universe, galaxies in all directions. Is there universe beyond that? Almost certainly, but we have no way of knowing how much, or whether it curves in on itself eventually, as many physicists suspect.

But what this wild profusion tells us for sure is that creation proceeds on an unimaginable scale, much of it unseeable and unknowable. Billions and billions and billions of stars and galaxies and black holes and who knows what else in this expanding realm we call space.

Our small story is dependent on that big story. So let’s return to it.

Celestial Cuisine

If we’re thinking in terms of what’s necessary to make us, what we need at this stage of the game are planets, so that one day there can be a planet for us. The thing is, to have a planet with somewhere solid to stand, we had to have heavier elements than the hydrogen, helium and lithium that were the main components of the earlier universe. It turns out that the stars were cookhouses for all the other elements, including carbon, vital to all life that we know of. But those elements had to be in the oven a really long time, about ten billion years from the Big Bang to be produced in terrestrial quantities. And then the stars that were doing the cooking had to go supernova or somehow explode, so as to spread the mineral wealth around to younger stars that could capture those blobs of heavy star matter and fashion planets from them. And it turns out that a star dying in that fashion is not necessarily inevitable. Certain chemical and physical properties are required, or the star goes out in another way.

But there were enough supernovas that eventually planets became commonplace anyhow. Scientists estimate there may be 1024 planets out there.

Of course it isn’t enough that there are planets. Not just any planet will do to support life – at least not carbon-based life forms like us. And here I’m going to paraphrase some of what Stephen Hawking and Leonard Mlodinow say in their recent book The Grand Design: About half the stars out there are in pairs, circling each other – not good for life on the planets that circle them.

The Goldilocks Orbit

You need a planet with an orbit that is nearly circular rather than elliptical – which is good for keeping temperature relatively constant – because life does not favor wide variations in temperature. And you can’t get circular orbits around double stars. So there had to be single stars. And orbits work in only our three dimensions, which makes it handy that the other dimensions are tucked out of the way somewhere.

You need a planet with the right distance from the star it’s circling. To make it concrete, in the case of our earth, if we were 20% closer to the sun, we’d be hot as Venus, and if we were 20% further out, we’d be as cold as Mars. And there’s another important result of the so-called Goldilocks zone we exist in: liquid water is possible. Our lives are nearly unthinkable without a world in which there can be liquid water, frozen water, and evaporated water.

Also we need to have a magnetic core if only to allow us to form radiation belts that keep harmful radiation away from the surface.

Beautiful Volcanoes

What’s another vital thing for our lives here? An atmosphere. Scientists think we have volcanoes to thanks for that – another reason we needed a molten magnetic core on which tectonic plates of earth could float and rupture and collide and give us beautiful volcanoes. Volcanoes spewed water, carbon dioxide, and ammonia, from whence what we breathe ultimately evolved. Also our oceans.

And we received all of that. To me, that feels so like running the table against long odds, there almost has to be a God in our corner, making it happen.

Of course, it would feel less miraculous if we knew it were commonplace. But we have no comparators.

Four Necessary Things

And on that subject, let’s talk numbers. I’ve read that there are perhaps 500 planets in our galaxy that fulfill the four conditions for life as we know it: a) correct orbits that preserve moderate temperatures and don’t run through radiation zones, b) made of rock, c) possessed of a molten core, and d) capable of holding an atmosphere. On the assumption our galaxy is typical, multiply that 500 by 100 billion, the number of galaxies we can see, and you get an estimate of 50 trillion planets throughout the cosmos that might have the requirements for supporting life.

And yet, so far as we know, we are alone. The problem is, it’s not clear how we’d know if we weren’t. Think of what would have to happen for our neighbors to know about us. The most likely way neighbors would learn about us would be to pick up on our radio and TV signals, now that we are emitting radio waves 24/7. But we’ve only been broadcasting for a little less than a century, meaning that our earliest transmissions are only 100 light-years out at this stage. Hence our radio transmissions can have only reached about 500 stars so far, because all the other stars are further away than 100 light-years. And 500 is an infinitesimally small proportion of the stars that are out there even in our galaxy. So, turning it around, if other planets out there supported radio-broadcasting life forms who developed at the same time as we did, they’d have to be on planets around one of those 500 stars in order for their radio transmissions to have reached us yet. The odds of that happening would be vanishingly small. And if the radio-broadcasting neighbors happened to be on a planet circling the furthest-away star within our own galaxy, they would have had to have sent out their signal nearly 100,000 years ago for it to reach us today.

So we have no information. We don’t know whether we’re rare or commonplace. But I think Genesis speaks to us either way.

If We’re Unique

Say we’re rare, that this whole vast creation contains nothing else like us. A 91-billion light-year wide cosmos, filled with billions and billions of stars and black holes and planets, etc., just so there could be an us. It’s conceivable, but at the same time insane. What could we possibly think about a God who would paint so long and so hard on such a stupendous canvas, when the most interesting and important detail was all encompassed in one little speck buried in some off-center part of the picture that no observer could possibly see?

Because of that apparent mismatch between us and our setting, the response of skeptics has been to propose a concept of the universe as a one-armed bandit whose handle has been pulled trillions of times. The evolution of every star, every planet, counts as a pull. All the planets that don’t meet those four preconditions for life are just bets that didn’t pay off. But a certain number of those planets, as we’ve seen, do meet those conditions. They pay off, somewhat. Most of them won’t be jackpots, though. The planets that meet the conditions of life but don’t develop carbon-based life forms, or get hit by an asteroid that blows them apart, or get swallowed up by a supernova or a plague or a volcanic eruption that destroys all life, or do develop life that never becomes intelligent, or do develop that kind of life, which goes on to destroy itself by engineering its own ecological catastrophe or killing itself off with warfare, or what have you, they’re not jackpots. But with trillions of pulls, the theory goes, everything is bound to line up at least once and yield the jackpot of intelligent life. No God guiding it and looking at it afterwards and see how good it all is; just the operation of the odds.

To which a believer might respond: yeah, but who set the odds in the first place? Where does this one-armed bandit of a universe with all of its laws and all of its huge capacity to allow trillions of opportunities to create intelligent life come from? Maybe the very reason there’s such a vast cosmos is that its creator knew how many tries would be required to bring about something like us. That might explain the otherwise apparently insane profusion of creation. Of course it would leave open the question of why God created a universe that made it so hard to achieve what God was aiming at. But it’s hardly irrational to infer a divine hand behind the workings of nature, even if we don’t have much of a clue why those workings were ordered the way they are.

If We’re Nothing Special

Or let’s try the opposite tack. Let’s say we’re nothing special, and that races like us are seeded throughout the universe, perhaps all unaware of each other. Genesis, of course, was written without notice of these other planets and other races. But the basic insight there: that what was done was done to set the table for our existence and survival: that would seem equally adapted to every planet that hits the jackpot and supports intelligent life. The more such planets there might be, the less urgent the questions we’ve just been grappling with. If it turns out that the making of planets that support intelligent life is relatively commonplace, then it would seem that God would have been aiming to create a lot of separate good things. That seems reasonable.

It would raise some interesting questions, to be sure. We used to hear Fr. Lawrence entertain them: Would there be separate incarnations there? Separate original sin? Separate redemption? You might recall that C.S. Lewis speculated about just this question in his science fiction novel Perelandra, set in a world which had not yet fallen and into which sin had not yet entered. (The mission of the hero was to prevent those things from happening.) I read neither Genesis nor any other part of the Bible as ruling out such things. Until we have a known instance of any other intelligent life out there, however, it’s all speculation.

What we do know, from Genesis and from what is in our hearts, I am sure, is that what God or nature has gifted us with is good, is sacred, and necessary for us. It seems that we now increasingly have the means within our grasp to reject that gift. We can poison the ecosphere or blow up the whole human species or even all species. We can exhaust some vital natural resource or tear down resistance to some virus that will kill us all.

Too Sickening to Contemplate

Think of this reality in relation to the two basic scenarios I’ve posed. Let’s say that this whole unimaginably vast creation was truly just about us. Are there words for what a tragedy it would be if we extinguished the whole point of not just our own earth but of literally everything, including all the billions of galaxies and trillions of stars? If we wiped out, not just the few billion humans involved, but literally the meaning of everything?

The prospect is only a little more endurable if it turns out there are other inhabited worlds. Maybe the jackpot we could have embodied got wasted. Maybe God built into the odds that there would be late-breaking failures like us. Maybe, even having sent the Redemption and the Resurrection we celebrate this night, God has not persuaded us to abandon suicidal destructiveness. Maybe we just didn’t have what it took to make the grade. And hopefully some other beings somewhere else will succeed where we failed, so that God’s plan may be realized somehow, somewhere.

Personally, I recognize the possibility of that outcome, but I refuse to reconcile myself to it. To me, and hopefully to all of us here, that sickening kind of failure is not an option. To me, looking at the vastness of the universe, with all that light, all that activity, all that excitement – all of which God sees and thinks good – I take heart. Though I do not know much about saving a planet, I sense that the purpose of this stupendous undertaking will not be easily frustrated, and that somehow I and you and all of us will be shown ways to contribute to keeping the show going.

Copyright (c) Jack L. B. Gohn

Religious Writings Page | Previous Religious Writing | Next Religious Writing