Still Chilled

Theme Songs Page | Previous Theme Song | Next Theme Song

Still Chilled

In the Still of the Night, by Cole Porter, performed by Carly Simon (2005), encountered 2006

Buy it here | Video here | Lyrics here | Available on Spotify | Sheet music here

In the Still of the Night suffers from the overfamiliarity that plagues too many songs in the Great American Songbook. We don’t really hear it. There’s a prettiness on the surface that belies its rawness and insecurity, its desperate plea for an impossible reassurance.

No Satisfactory Answer

Think about it.

The lover asks this loaded question:

All the times without number

Darling when I say to you

Do you love me, as I love you

Are you my life to be, my dream come true

Or will this dream of mine fade out of sight

Like the moon growing dim, on the rim of the hill

In the chill still of the night?

And how could the beloved could ever make a satisfactory answer? Beloveds, no matter their devotion in this moment, can’t know the future. Humans change over time, and beloveds are only human, and hence, with the best will in the world, they cannot issue unqualified guarantees. And worse, even the beloved’s present sincerity is not totally knowable.

Not Just Constancy

Nor is the lover’s question just about the beloved’s constancy. The beloved’s survival also enters into the question. Every affair or marriage, no matter how devoted the parties, will end one day, and (barring what lawyers call a common disaster), one of the parties will have to live with the loss.

In short, the lover’s insecurity is not unreasonable. But it can easily be unreasonably extreme.

My mother felt such extreme insecurity more than anyone else I ever knew. In retrospect I recognize that I was the truest love of her life, and that my infantile adoration, while she received it, was the sweetest feeling she would ever feel. And she received it for a long time, probably longer than she had any right to expect; most boys my age seemed to move on quicker than I did. Yet, eventually I saw my parent’s limitations, and the need to adjust my previously uncritical response, as all children eventually do. To her dying day my mother could never accept this inevitable nuance. Nor could she truly accept my subsequent commitments to lovers, spouses and children, friends and work, which were all experienced as deep wounds and neglect, even at times apostasy and treason.

And this became the great tragedy of her life. My mother could neither understand nor consent to a mature love from me, and, try as I might, I could not propose to love her in any other way. Her demands grew increasingly strident, and my resistance increasingly cruel-seeming to her, and sometimes to me.

The Central Question

Yet I was not blind to what underlay her insistence: that all-too-human fear of the oblivion of love of which Cole Porter wrote.

After she died, I had occasion to ruminate bitterly on this, largely while I was on the road. I did some traveling in her wake. Though she had passed her last couple of years at a senior community in Baltimore, we had decided years earlier that her ashes would be immured next to my stepdad’s in Ann Arbor. So there was a visit home for a funeral and a memorial service. And then there were two more visits, because I wanted to write about the re-encounter with my home in the middle of my life, to use Dante’s phrase, and wanted to do some research, as well as to mourn in the place that felt most appropriate for this particular siege of grief.

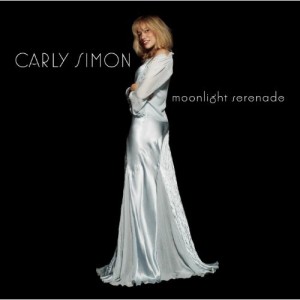

On the road, I was frequently playing Carly Simon’s previous year’s album, all standard love songs, called Moonlight Serenade. One of the cuts was In the Still of the Night. And when the lyrics came around to that lover’s question, I realized it was the central question of Mother’s life, for many years and certainly towards her sad end, an end rendered heartbreakingly solitary by the dementia that had shredded continuity in most of her relationships.

Now It Was My Question

But now that question had become my question. I did not, could not, love Mother as she had loved me, but that is far from saying that I did not love her. Of course I did, difficult as she had been. And now she was not there. So what did that mean? Had she and our relationship just faded out of sight, as Porter so aptly phrases it?

Up until that very point, as I said in the preceding piece, I would have answered as my religion had taught me: that the relationship was still there, and that, even though I could no longer see her, we were still connected. That, in fact, our relationship would be fully restored one day in an afterlife.

But I could not feel it. Not this time; I’d felt it somehow when I lost my father and when I lost my stepfather. With Mother there was no sense of assurance, none of continuity. And I was feeling exactly as the lover in Porter’s song dreaded to feel: left “in the chill still of the night.”

Still Chilled

It’s hard to overstate what a shock this “still chilled” feeling was. I had always been a cheerful person, an optimistic person, no matter what difficult or sad times I might be passing through. Now, though I had hardly lost the ability to be happy, the default setting of reflexive cheerfulness had disappeared. I could not shake and – to this day over ten years later – have still not shaken the opposite reflexive sense, one of isolation and doom.

I had to conclude that, unbeknownst to me, and with all the difficulties between us, my mother had somehow been the indispensable prop of my sense of well-being, and that there was nothing to replace her. In saying this I do not slight any of the others who were close to me, my wife, children, or colleagues. I depend on them even more now. But still something essential to everyday happiness has to my astonishment departed.

And as I was quickly discovering, and will discuss in the next piece, other things had departed with it.

Copyright (c) Jack L. B. Gohn, except for album artwork