A Half Day

Theme Songs Page | Previous Theme Song | Next Theme Song

A Half Day

The Seven Tin Soldiers, by Papa Dee Allen, Harold Brown, B.B. Dickerson, Lonnie Jordan, Charles Miller, Lee Oskar, and Howard Scott, performed by WAR (1977), encountered 1978

You Better Come Home

I still possess carbons of the green daily report sheets I used to turn in to record my engagements as a court reporter. The sheet for Thursday, May 4, 1978 reflects a “Half day” in the Superior Court grand jury down below Washington’s Judiciary Square. About mid-day, someone had reported there was a call for me (a rare thing), and when I got on the phone, it was my wife. “Honey, you better come home,” she said. The way people say things like that, you immediately know someone has died. “What’s happened?” I asked, wondering who among our vast network of family and our narrower network of friends might have left us. S. did not want to say, but eventually she let me know: it was my father. And so home I came.

I was astounded. At 28, I didn’t know anyone who had lost a father, and I’d seen mine in February. In fact, I’d spoken with him in the past week. And when I thought about that call, my heart sank, not because of what had been said, but because of what hadn’t.

The Short Straw

Some background: I had not lived with my father since I was five, and along the way, as must happen when parents go their separate ways, someone got shortchanged on the intimacies and joys of parenthood. My father had been the one to draw that short straw. But as I grew up and especially as I married and became a parent in my own right, my dad had begun to regain some ground. I was proud of my father, a Harvard-educated former diplomat and professor of economics at Columbia. I was trying to be more like him, which obviously wasn’t going to happen while I was working as a court reporter. So I was putting in motion various plans to move on. (Applying to law school, buying a new house, putting a novel I’d written into the hands of a typist so I could try to publish it.)

But when I’d seen him in February, those plans were still in fairly rudimentary shape. The disparities were on display, when we’d met up at Union Station in Washington on a Friday as I was coming off work in the grand jury (taking down other people’s words) and he was coming from a conference of government policy-makers at which he’d been a speaker (having people listen to his words). The two of us had ridden up to Baltimore on the last car of a train, right at the back, watching as the right-of-way receded behind us and the sun sank low in the west. It had been a moment of quiet intimacy, flavored by the half-and-half nature of my achievements thus far. I knew he sympathized greatly with me for my becalmed career, and shared my hope that I would move on. On the plus side, I had two lovely children to present to him, and a house purchase under contract. But I had not yet completed the law school application, and was still not clear in my own mind that law school was what I wanted to do, or indeed what I wanted to do.

Maybe You Had to Know Him

I know he was warmly appreciative of what I did have to offer. He’d written me and my wife in early January: “Every time I am with you I am surprised how much I enjoy the parental role. It is one I’ve rarely exercised, and one I did not suppose was particularly congenial. Yet I seem to get increased pleasure from it.” Well, maybe you had to know him to recognize that this was effusive praise; trust me on this.

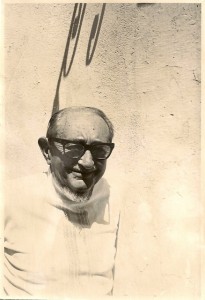

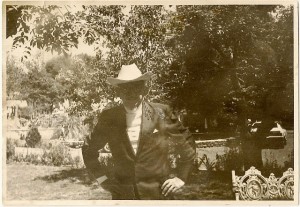

To all appearances he had been still bursting with life. After that February encounter (and it kills me that I have not the slightest recollection of our final goodbye on the Sunday after that train trip), he had gone back with my stepmother Etta down to San Miguel de Allende, Mexico, where the two of them maintained a winter home. In a late letter, he’d enclosed a trio of photos, two of which I copy here, both taken, I believe, at the Instituto Allende, the art college, where I think he was taking a class. On the back of the photo of him in the sombrero, beaming in the garden in the bright sunlight, he had written “Lush, eh?” Clearly this was a man still instinct with curiosity and excitement.

To all appearances he had been still bursting with life. After that February encounter (and it kills me that I have not the slightest recollection of our final goodbye on the Sunday after that train trip), he had gone back with my stepmother Etta down to San Miguel de Allende, Mexico, where the two of them maintained a winter home. In a late letter, he’d enclosed a trio of photos, two of which I copy here, both taken, I believe, at the Instituto Allende, the art college, where I think he was taking a class. On the back of the photo of him in the sombrero, beaming in the garden in the bright sunlight, he had written “Lush, eh?” Clearly this was a man still instinct with curiosity and excitement.

Yet he was also a diabetic with a related heart condition, and in the end, that was what won. On the morning of May 4, less than two weeks after his seasonal return from Mexico, he suffered a heart attack, and died in the hospital shortly thereafter. Gone before I knew there was a problem. Oh, I knew he suffered from diabetes, but I didn’t really know what that was, I was so young and ignorant.

The Too-Late Machine

I’d spoken with him the last time, I think, the Saturday or Sunday before. To this day, I feel terrible about that call. My offer of a place in the University of Maryland School of Law had been in hand about two weeks at that point; I had just made up my mind to accept. (I think I mailed out my intent to attend the day after the call.) But when Dad phoned in, I had been working feverishly to finish typing the transcript of an extended hearing about unionization of a company that made fire alarms and security equipment. I’d been called up to answer the phone from my typewriter in the basement and was eager to get back. I fielded it in the wall phone in the kitchen without sitting down. I did not volunteer any information about this momentous change I was about to go through, and my dad did not ask, though he knew I had an application in. I would very much have wanted him to know about all this, but I was too caught up in my preoccupations of the instant to share it, be it ever so important. And then suddenly it was too late.

That is what death is: the too-late machine; it stamps out a point beyond which nothing can be made right.

How We Mourned

We coped medium-well with our losses. Quakerdom and academia did their unimpressive best to memorialize the man, at a memorial service attended mostly by members of my parents’ Friends meeting and my dad’s Columbia department. No one said anything much; I vividly recall the chair of the department, a man named Boris, trying to think of something piquant to say, making some idiotic remark about the exotic airline bag my dad would carry.[1] My stepmother and I nearly quarreled about my inheritance – friction I swear to this day I did nothing to create or exacerbate, though I did feel I was due something. She acknowledged her moodiness in a note, but of course we were all moody then. (And almost immediately that inheritance had a major influence on my life, making it possible for me to transfer before the school year started from night school to day school; I’ll talk more about that in a subsequent piece.)

So I was left to mourn in my own way, in the midst of a house move and in the midst of a huge change in my life. By now the reader knows me well enough to know music would have something to do with it.

How I Mourned

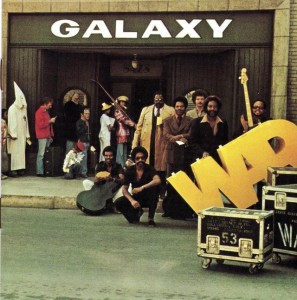

A record I had on loan from the Towson Library when all this struck was WAR’s Galaxy (1977). WAR was a crew of mostly black Angeleno musicians who had been assembled originally to back up a white Brit, Eric Burdon, late of The Animals. But Burdon had split from the group, which had gone on to forge several hits of its own, relying on such things as a weird combination of funk and Latino sound, as well as the unique combination of sax and harmonica playing together as a brass section. And this would prove to be the last album made under the WAR name by that core group. The last song of the last album by this group was a powerful 14-minute tour-de-force which for my money always seemed elegiac in the extreme.

The title is The Seven Tin Soldiers, and there is something a little march-y about it, and I’d assume that the Soldiers are the seven members of WAR marching along, so this seems to be a musical group portrait of them at the very end of their time together.[2] But despite the egalitarian name, the song belongs to the harmonica player, Lee Oskar, who wrote the melodies that hold the song together, and whose solos dominate the song. The principal melody is funky and mournful – and increasingly virtuosic as the piece proceeds.

And I found I could sort of play along with it. I was using a chromatic harmonica and Oskar was using diatonics (which I did not then know how to play),[3] but still I could chime in with most of it. Our new house had a sunroom with a western exposure, and there I stood, one afternoon shortly after my father had died and we had moved in and my life was all jumbled up beyond recall, with the light of the dying day filtering in through the tree outside, tears welling up as I honked through a requiem for my father with the instrument I knew best how to play. And in the last three minutes, the chorus of Scott and Dickerson and Allen and Miller would rise in the background and propel the song to a height of emotion that nothing else could express.

[1] At least the chair got the name right; my father’s name was Emile, but the New York Times obituary rendered it as Emil. I inadvertently got the chair back and in a fashion quite similar to that of the Times; in the acknowledgments of my father’s last book, which I edited and saw through the press, my proofreading let slip a typo identifying the poor chair as “Doris.”

[2] In the Barry Alonso liner notes of the 1992 CD rerelease, Oskar is quoted as saying he wrote it “thinking about all the band had survived and done together. I’d always been a Hans Christian Andersen fan, so I thought of us as being like the seven tin soldiers coming back from the war, with the clock ticking.”

[3] I don’t know if he was also using a variation of diatonic harmonicas Oskar brands under the name “Melody Maker,” which I’ve never tried to play. But while I believe most of the song was played on a standard G diatonic harmonica, there are notes in the song that did not come from such an instrument.

Copyright (c) Jack L. B. Gohn, except for album graphics