Parenthood on the Hoof

Theme Songs Page | Previous Theme Song | Next Theme Song

Parenthood on the Hoof

Gonna Fly Now (Theme from “Rocky”), by Bill Conti, lyrics by Carol Connors & Ayn Robbins, performed by Maynard Ferguson (1977), encountered 1977

Buy it here | See it here | Lyrics here | Sheet music here

Running: that was the way I summoned joy and the way I expressed it in 1977. That year saw the dawn of the great jogging era, the publication of Jim Fixx’s Complete Book of Running, and the first Rocky movie (well, to be technical, released in December 1976). No one who ever saw that movie forgets The Scene: the one where Sylvester Stallone whips up some horrible nutritious concoction in the blender, downs it, and goes out for a training run through the predawn streets of Philadelphia. The scene morphs into a montage of boxing training footage, but then returns at the end to Rocky’s run, memorably topping off, literally and figuratively, looking eastward into the rising sun from the summit of the grand staircase in front of the Philadelphia Museum of Art, as Rocky flings his arms triumphantly into the air. All of this accompanied by Bill Conti’s soaring, pulsing theme song Gonna Fly Now, periodically propelled by swells of strings that communicate to every listener the sheer transcendence running can produce.

The Endorphin Rush

The Scene probably bred far more runners than Jim Fixx ever did, and led many of us who had no business lacing up jogging shoes to try living that dream for a while.

And I was one of them. I have preternaturally tight hamstrings (which I kind of knew) and a tendency to disk degeneration (which I guess I didn’t). Despite my body telling me there wasn’t something quite right about it for me, I was out there on Baltimore’s streets, and sometimes Washington’s when business took me there, three times a week. I was to pay dearly for it; I consider my three later back surgeries to have been secondary (at least in part) to injuries I inflicted on myself then.

But no matter: the immediate effect at the time was sheer joy. The Endorphin Rush was real, and I got hooked on it. No matter that my life and career had veered wildly off course; I still had a way to feel great as my feet were guiding me around, say, the Guilford Reservoir a few blocks north of our house.

Nosebleed-Inspiring

And of course as I did it, my breath got all rhythmic, and mentally I was singing songs to myself that went with the ragged pace of my breathing. Later running would involve Walkmen (Walkmans?), but those were a couple of years off yet. In a time before earbuds or even headphones, my own voice was the only portable sound source. And so voice it was.

And for jogging I couldn’t hum just any song to myself. Only certain songs had that power to make you run. Gonna Fly Now was, predictably, a regular feature of my under-the-breath playlist. In the Maynard Ferguson version, that is. Though I saw the movie when it came out (who didn’t?), it was not really the Bill Conti soundtrack version I knew. Ferguson, a jazz trumpeter of formidable power and control, was never above jazzifying what was new and hot in the world of pop music. And frequently he moved as fast as the pop charts did. To choose the obvious instance, the release of his version of Gonna Fly Now was effectively simultaneous with the release of the Bill Conti original.[1]

This adaptation was everything you could want in a 1970s running song: pulsing disco beat and soaring fills and solos by Ferguson that took the melody to nosebleed-inspiring heights.

Outshining the Original

I don’t expect anyone would disagree that Ferguson’s adaptation outshines Conti’s original. Whereas Conti relied on strings and a wall of sound to add the sense of lift and elation, and this does work, Ferguson’s soaring solos are simply gutsier, more powerful, and more musically inventive ways to stimulate the same emotions. They are more in keeping with the dynamic of Conti’s own melody than what Conti does. Something about the song just calls out for a reach to the upper registers, which Conti does not do much but Ferguson does a lot – goes all the way up to three As above Middle C.[2] And not timidly: explosively, warbling at the heights.

Of course, what Ferguson could do with one of his custom-designed trumpets was far more impressive than anything I could have sung, even if I hadn’t been running, with my non-custom-designed voice. But no one else ever was intended to hear me, or did. So I was happy.

Celebrating the Arrival

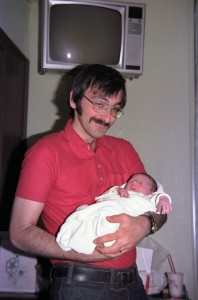

I vividly recall one run with that number on my lips, the day Andrew, my first son, was born, in June of 1977. For medical reasons, this was a scheduled birth. We went into the hospital early in the day and by the afternoon I was holding my son in my arms. The photo to the right, the first of Andrew and me together, was probably taken that evening. But in between, after the suspenseful, impatient wait in the lobby, I left his mother to sleep for a while, drove home and – went for a run.

I vividly recall one run with that number on my lips, the day Andrew, my first son, was born, in June of 1977. For medical reasons, this was a scheduled birth. We went into the hospital early in the day and by the afternoon I was holding my son in my arms. The photo to the right, the first of Andrew and me together, was probably taken that evening. But in between, after the suspenseful, impatient wait in the lobby, I left his mother to sleep for a while, drove home and – went for a run.

I’m the father of three, and I know there’s no accounting for anything in the feelings of parents. But whatever the reasons, this was the most euphoric I ever was over the arrival of a child. I felt – I don’t know – limitless, transcendent, as if I were floating rather than running.

It was a very good moment, one I shall always treasure. (As I do the son who occasioned it.)

A postscript: If you want to see a tribute to the Ferguson performance that, for sheer excitement, tops even the Master’s effort, click here. It may not be quite definitive, but damn! is it good.

[1] I’m unable to determine when, exactly, in 1977 the Rocky soundtrack album was released, but Joel Whitburn’s Top Pop Singles reflects that the Conti Gonna Fly Now single was released on April 23, and that Ferguson’s single was released the very same day. However, Conquistador , the album that had Ferguson’s version on it, was released in January, per allmusic.com. Since you can’t get much earlier in 1977 than January, we have to conclude that Ferguson’s album came out simultaneously with the soundtrack or even before it. And, as noted, the singles were released simultaneously.

[2] At the end of the Conti record, the strings briefly hit the E below that A, but in a somewhat understated way. Ferguson busts up into that territory several times, and loudly. For the most part, the Conti version succeeds by confounding expectations and going down where the ear expects the music to go up – and by doing so in muscular fashion, like a boxer aiming for the body when you think he’s going to punch for the head. Ferguson did the more obvious thing, but there was a reason it was more obvious.

Copyright (c) Jack L. B. Gohn