Imagining A Lot(tery)

Theme Songs Page | Previous Theme Song | Next Theme Song

Imagining a Lot(tery)

Imagine, by John Lennon (1971), encountered 1971

Buy it here | See it here | Lyrics here | Sheet music here

Imagine: The lucky guy has just been given his life back, and mine has been taken.

365

Imagine: A college quad at night with someone running across it screaming “365! 365!” It is December 1, 1969, the date of the first draft lotteries. The lucky screamer, born February 26, has just been given his life back. Whatever plans he’s made for his future are secure, at least from the threat of being called away to take part in that bigger lottery called the Vietnam War. There’s no chance that Number 365 will be inducted. Not only will he be spared the certain sacrifice of two years of his life, but he is immune to the risk of the even shorter straws: killing, dying or being wounded.

Imagine: A crowd of us sitting together a few moments earlier in Houston Hall, the student union building, listening to the draft lottery being broadcast.[1] Afterwards, I wander despondently out onto College Hall Green, where the shouter sprints by. I am filled with envy and terror. Since I was born on a July 13, my number is 42. My prognosis is the exact opposite of Number 365’s. While I remain an undergraduate, I will be protected by a student deferment. But when I graduate, as inevitably I shall in only three semesters’ time, they will reach me. If the War goes on, as I know it will, and I do not find another deferment, as I doubt I shall, it is a certainty.[2]

42

Imagine me speaking to my parents by phone later that night. I curse at my mother, and, with rare restraint, she takes in both my anger and its untoward expression without an angry reply. Much later, after I have children, it will be obvious why. A threat to me is a threat to her. Still, little in her experience could lead her to accept my outlook.

It’s no problem imagining what has formed her views. She has been through the Second World War. She is no flag-waver, but she remembers her pride in the young GIs she met in the trains in those days. Nor has anyone had to sell her on the evils of Communism – and Vietnam, they tell us, is a war against Communists. No doubt she and millions of mothers like her feel instinctively that Horace was right when he wrote: “Dulce et decorum est, pro patria mori” (It is sweet and fitting to die for one’s country). You support your church, your political party, your nation, and your nation’s wars: that is her outlook. And these loyalties might call upon you to surrender up your only son. Bring on the sweetness and the fittingness! Up to this moment, I think, that conclusion has also been part of her outlook.

But now she has to imagine a contradiction to all that.

Imagine me seeing nothing sweet or fitting about dying, fighting, or putting myself at risk for Richard Nixon or his evil war. From the moment in February of the previous year, during a poetry reading by Allen Ginsberg, when I had realized that I now opposed a war I had once supported, I am growing more and more horrified at the holocaust of young men, American and Vietnamese, the War is creating. That type of sacrifice might be justified to bring about a world without Hitler, but hardly a world without Ho Chi Minh.

Holding Off Catastrophe

And now it becomes up to me to imagine ways to avoid this catastrophe bearing down on me. I try. I borrow books from my parish priest about Catholic views of war. I thus become knowledgeable about Just War Theory. I apply for conscientious objector status, but my Draft Board turns me down, unconvinced that I am against all possible wars, and concluding that my convictions are firm only about the current one. I blush, because they have seen right through me. I apply for a medical deferment on the basis of back pains I’ve been having. I learn that I’m the third generation of my family with wretched backs, that my mother has often been in traction. I get the doctor mother of Carol, the friend who lives in our house, to write a letter supporting my deferment claim. I undergo a couple of draft physicals, one in a big tall building off Broad Street in Philly. My medical deferment claim is rejected. This time the call is wrong; I’m not malingering. (In later life my back will be operated on three times.) But the maw of Moloch must be fed, and questionable deferment claims must be rejected.

Imagine the inner dialogues, about the reality that, if I make good my escape from military service, someone else will have to take my place. Imagine me deciding that if the worst comes to the worst, I will flee to Canada, because I will not accept either service or imprisonment. Easy to say, but flight would mean disruption of my graduate studies and those of my young wife, and, so far as I know, I would never be able to come back to the United States to visit parents or in-laws or friends. Imagine the misery drawn out, as my deferment fights defer the moment when I am required to report for induction.

Reprieve

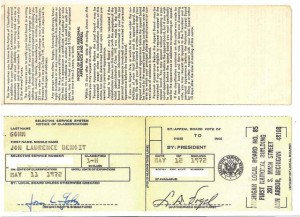

Imagine May 11, 1972, the date my Draft Board, for reasons that elude me entirely, reclassifies me 1-H. I open the envelope and see the card, and realize I’ve never heard of 1-H. It turns out that 1-H means not available for induction. The card looks like, and in fact turns out to be a reprieve, one I had not even sought. In later years I will hear rumors that it was issued to people suspected of being gay, but also that it simply meant that for whatever reason, you had not been inducted in your “year,” and so the Board was moving on to the next year’s candidates. (The timing would pretty much work, since when the card arrives, I have been out of college and undeferred for about a year. In which case, my sheer persistence in seeking a deferment has paid off after all, unimaginably well.) In any case, no one ever tells me why, then or ever.

Imagine how I feel after it sinks in. While I also understand that a 1-H is subject to reclassification as 1-A at any time, I never hear from the draft board again. And now it is my turn to feel that my life has been given back to me.

A Song on the Radio

Later, I can remember myself very shortly after I know I’m probably saved, driving down Light Street in Baltimore, when John Lennon’s Imagine comes on the radio. I dissolve in emotion. It’s not simply that Lennon is asking us to imagine a world without war; he sees war as part of a complex of bad things:

Imagine there’s no countries It isn’t hard to do Nothing to kill or die for And no religion tooAt this point in my life, I’m a very serious Catholic, but I understand the role religion has played in so many wars, so I’m not blaming Lennon for his point of view. I think it a perversion of religion to go to war for it, so I can agree with his diagnosis without signing on to his prescription.

But the way I respond goes to something far deeper than that: it’s the heartbroken melody, those langorous piano chords. To be sure, there’s a hopeful note in there. But mostly Lennon’s voice comes across as exhausted by sadness. And it speaks to me because that’s how I feel after this close encounter. I could have been a war casualty; I’m not, thank God. But I tell myself I must never forget what it felt like nearly to have been one. I must not forget the months of dread, of helplessness and anger. I must not forget the way the good and patriotic motives of my countrymen were put in service of bloodthirsty insanity that threatened my life and my life’s plans. And I never do.

Closing Vision

But beyond even that, I resolve never to forget Lennon’s closing vision:

Imagine all the people sharing all the world You, you may say I’m a dreamer, but I’m not the only one I hope some day you’ll join us And the world will live as oneAnd I never forget that, either.[3] If you can imagine.

[1] Just possibly watching it on TV: my memory is vague on this, but I know where we were sitting, and I cannot picture a TV set there in that era.

[2] I had been trying to find words to convey what it felt like to be told that, by the random operation of a lottery, your country had slated you to (possibly) be killed. And then I saw the 2012 movie of Hunger Games, and it was there on the screen, in the reaping scene at the beginning, in the breathless look on the face of the heroine’s sister when her name is drawn in the lottery to participate in a fight to the death. I don’t mean to suggest the situation is a perfect parallel, but it captures the feelings perfectly.

[3] Not that Lennon was passive benevolence personified. If you listen to the Imagine album, the one the song came from – and you should – you’ll find it’s chock-a-block with violent emotions, including a savage attack on Paul McCartney (How Do You Sleep?) and the obvious remnants of a fight Lennon must have had with Yoko Ono (Jealous Guy). And this album is a step down from the primal scream that was John Lennon/Plastic Ono Band (1970), maybe the angriest album I’ve ever heard – and also one of the greatest. Nor is it possible to catch that line “Imagine no possessions” in the official video without smirking; as he lip-synchs that line, John is seated at a grand piano in a huge room, looking out over privately-owned gardens. He was maybe imagining no possessions but wasn’t exactly letting go of them himself.

Copyright (c) Jack L. B. Gohn, except for artwork