Theater Days

Theme Songs Page |Previous Theme Song | Next Theme Song

Theater Days

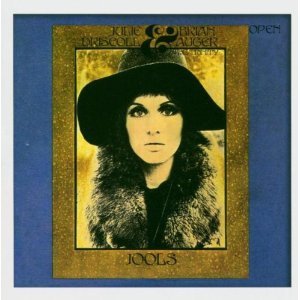

In and Out, by Brian Auger & The Trinity (1968), encountered 1968

Buy it here | See video with original piece here

Gates of Eden, by Bob Dylan (1965), encountered 1968

Buy it here | Video with original piece here | Lyrics here

I was theater-smitten before I ever got to college. By my high school years, I’d accumulated over a hundred programs from shows I’d seen, and I could quote you a lot of Shakespeare. In high school, I’d appeared in three plays. Coming to Penn, then, I simply assumed that I’d get involved with the student theater company, and I did. That turned out to be the Pennsylvania Players. My resulting involvement with them ended up being tougher, shorter, and more interesting than I would have predicted. In the end, I took part in only three shows.

Armless in Philly

The first show was a big original musical about GIs and nurses during the Korean War. The hero: a concert pianist who gets his arm blown off in combat, but then discovers meaning in life taking care of a little girl with leukemia – a little too upbeat and square for a show being produced during Vietnam. I served as assistant stage manager.[1] Doing that, I bumped up against some truths that were somehow new to me, I’m not sure why, but which I found offputting. I learned that the theater is full of temperamental and cliquish people, for instance. I learned that kids with aristocratic pedigrees from Philadelphia’s Main Line and similar spots further up the Eastern Seaboard had a sense of entitlement, not to mention quaint names.[2] I learned that some of the people in theater were highly flirtatious, and that in an organization drawn from four college classes, a lot of the romantic histories and/or rivalries among the older members were important, extensive and not readily learned by newcomers. Knock me over with a feather! The effect was sort of Rosencrantz and Guildenstern-y, with me stuck occupying a corner of a scene that other people were barging into and out of with little heed to me.

Despite these shocks, I managed to do all right with that show, and suddenly started “feeling the love,” in the modern phrase. (I burbled on to my parents “The first thing I discovered is that they are sort of a closed organization…. The next discovery I made is that they love me and look upon me as some sort of a whiz kid.”)

The Bottom Rung of the Farm System

In recognition of my success, I was now placed in line to direct a show somewhere further up the line. My next step, in the spring, was being given a stage manager position on one of an evening of short plays (see the program here) that had won an undergraduate playwriting competition. Unlike the very limited assistant stage manager role on the big musical, this was effectively an assistant directorship, and looked on as readying me to direct.

I surely don’t want to exaggerate how much of a step up this was for me. Looking back, I can see this was the bottom rung of the Penn Players’ farm system. The play we were given, called Blues Man, by a senior we’ll call Chaim, was described by him in a handwritten note on the script as: “… the story of the necessary self-destruction of an emasculated white liberalism and the subsequent emancipation of the Negro Psyche.” This two-character piece concerned the fracturing of a friendship and working relationship of a pair of jazz players, as the black one rejects the well-meaning but ultimately blind and patronizing support of the white one. As the (white) author pointed out to me recently, this was sort of an attempt to follow in the footsteps of black playwright Leroi Jones (these days known as Amiri Baraka). Actually, for juvenilia, the play’s not all that bad. But with the strained resources of talent Penn Players devoted to it, we made a hash of it.

Beyond the fact that we wrote the play a new ending and destroyed the playwright’s vision, we had no cast. For the angry black man we had a whimsical and utterly unmenacing guy I’ll call Charles. (He later married a white girlfriend.) For the white guy we had a foreign grad student with a significant accent I’ll call Dieter. Now, the white liberalism being dissed in the play was specifically American white liberalism. Foreign jazz enthusiasts, of that era especially, were just different from American ones; they liked and were reacting against different things. Dieter could effortlessly have come across as some kind of clueless foreigner, rendered insensible to the values of truth, justice and the American Way by too much food with garlic, powerful tobacco and reflexive Marxism. But he couldn’t be a convincing U.S. honky trying to sidestep white guilt. Also, he looked far more conventionally masculine than Charles. Acted that way, too. I remember him at parties, absolutely relentless in the pursuit of American women, which Charles never was, despite his quoting me the saw about “once you go black, you never come back.” In Chaim’s and Leroi Jones’ imaginations, this would have been wrong; the black guy should be the studly one, not the – to use Chaim’s word – “emasculated” white liberal.

We Couldn’t Do The Music

So, okay, we couldn’t do typecasting. Worse yet, we couldn’t do music, and that was on me. For our play, the choice of cue music for some reason was mine. Now you’d think that I’d have been sophisticated enough to realize that in a play about two blues-oriented American jazzmen, one of whom is black and plays the sax – the white guy tickles the ivories – we would lead in and out with small-group jazz that might remind one a bit of (but probably without actually being by) people like Coltrane, Parker or Rollins. But the sad truth was that I knew nothing about those guys in 1968. As I’ve said in another one of these pieces, rock was shouting pretty loudly in my ear right then.

I did have a jazz album, though: Open, by the Brian Auger Trinity, a bunch of Brits who had obviously heard rock once or twice. The rock intonations were probably what I liked about it – well, that and the cover photo of spacy but sexy Julie Driscoll, who, however, only sang on one side of the record.[3] So, making use of my limited repertoire of jazz records, what we hit upon to play for the cue-in music was In and Out from Open. So, yes, technically I got the small group aspect right: as the name implies, the Trinity were Brian Auger and two other musicians, a bassist and drummer. But the keyboard Auger was playing on this number was an organ, a Hammond B-3. There’s no better way I know to describe the performance than to call it jaunty, a Hammond tour-de-force. (You can listen to it by following the link above.) It was swinging more than soulful, funky without the spirituality of the Coltrane types. Kind of a strut with a sporadically walking bass line. Call it Carnaby Street Jazz.

Whatever I was thinking, and I swear I don’t know, the result was that my little musical contribution to the theatrical end product was to strip out any musical context for a racial argument largely couched in musical terms. And whatever I was thinking then, whenever I play that number or that album these days I think of my experience helping put on a little play in a strange and somewhat hostile environment – a sort of microcosm of how I felt about freshman year at a strange school in a strange city.

Glorious Rambling Nonsense

It’s not the only song that makes me think of the experience. You also have to take Gates of Eden into account. It was, as I have said, a three-play evening. The first play, called Necropolis, has vanished from my memory (and the author hasn’t answered my e-mails to remind me). But the music that accompanied it has not: Bob Dylan’s haunting, mystical, not-to-be-understood slice of what? Gnosticism? Apocalyptics? It was at about this point in the second semester of my freshman year that I was came to the realization that an English major would be a far safer course of study for me than a lot of other things. I was starting to think and listen like one. And my ear, increasingly sensitized by what I was getting in my courses, recognized both music and poetry amid the ramblings.

No mistake; the song did ramble. I defy anyone to make cold sense out of lines like:

The lamppost stands with folded arms. Its iron claws attach to curbs ‘neath holes Where babies wail though it shadows metal badgeSo one mistake would be to take every word as if it were seriously meant to denote something. Another would be to take the whole as if there weren’t something meaningful going on. There are two clear poles of meaning in the song. It starts and ends with wonderment at the elusive meaning of war, and it contrasts the bafflement and confusion the speaker experiences with the certainty of Eden. We know a few things about Eden; among them:

No sound ever comes from the Gates of Eden. You will not hear a laugh All except inside the Gates of Eden [which seems to contradict the previous point] There are no kings inside the Gates of Eden.And there are no sins inside the Gates of Eden.

… what’s real and what is not. It doesn’t matter inside the Gates of Eden.And there are no trials inside the Gates of Eden.

And there are no truths outside the Gates of Eden.

Was the land beyond the Gates of Eden real in the universe of the song? Unclear. And was the peacefulness of Eden anything more than that of the grave? Ditto. There was something uncompromising and bleak about this music, though, which made Eden seem forbidding, even with all these basically positive attributes Dylan posited. But I craved that bleakness for some reason.

Of course, like everyone in my generation, I’d been somewhat familiar with Dylan for at least three years. But I knew him as a protest singer (Blowin’ in the Wind), who also wrote grouchy love songs (Don’t Think Twice, It’s All Right), and grouchy songs in general (Like a Rolling Stone). The phase he was entering now, half Lewis Carroll nonsense versifier, half mad prophet, appealed to me much more.[4] It was around this time, as I recall, I spent a good part of a skiing trip at my dad’s Catskill cottage, with the two of us playing Blonde On Blonde[5] speechless with laughter. How can you not laugh at lyrics like:

The fiddler, he now steps to the road. He writes “Everything’s been returned that was owed” On the back of the fish truck that loads While my conscience explodes.This is so preposterous, so inconsequential, so syntactically wrong, the mind just goes into overload. And Dylan was churning this stuff out by the acre at this phase. But amidst the cheerful syntactical chaos, you could sense someone whose least utterance was powerful, whether for laughter, bleakness, or anger. Dylan was important.

So Necropolis was, in the final analysis, my real introduction to one of the great artists.

The Origins Story of an Ink-Stained Wretch

To jump ahead just a little in the story, there was, as I’ve stated, one more one-act play, the following academic year. This time I directed. I rubbed shoulders with some interesting people on this one. A future housemate of mine, a guy who went on to write for the New Yorker, and also ghosted the memoirs of a well-known madam was in my little cast. And in another play, the well-known musical theater critic Ethan Mordden (not the name he started at Penn with and not the spelling he used at that point of his apparently self-chosen name). The music was in the hands of a man who became a well-known Baltimore DJ during the album rock years. So there were interesting folk about.

But over that year, which was the first I had a real girlfriend, I made two discoveries. I found out that romance was a more interesting endeavor than the exercise in herding cats that theater was turning out to be – and that I liked reviewing theater for the Daily Pennsylvanian more than I liked producing it for Penn Players. Reviewing plays and musicals is a pursuit that has, off and on, lasted to this day. I remain a theater-struck ink-stained wretch, but with a face that has stayed innocent of greasepaint.

[1] See excerpts from the program here. (The rest had to be jettisoned for reasons of bandwidth.)

[2] The star was my dorm counselor, Bancroft Littlefield, Jr. (Or, from an etymologist’s perspective, Beanfield Littlefield.) Consider this comment bemusement at his name, not a suggestion one way or another as to whether he had what we moderns call a sense of entitlement, or any other kind of disrespect. He has apparently. and doubtless deservedly, become a name to reckon with in New England legal and political circles.

[3] The story here is a bit complicated. The album was a double album. The A-side was called Jools, and had the above-pictured cover of Julie Driscoll (known then by the nickname Jools, nowadays, 2011, performing under her married name Julie Tippetts). Reviewer Greg Boraman aptly summarizes her performance this way: “the seminal 60s hippy chick, sings with a stoned, disjointed charm to great effect.” (There are good videos of Jools performing cuts from the album with the Trinity here and here.) The B-side was just the Trinity. It had a matching cover photo of an overexposed (a word that happens to be apt as a matter both of photography and of decency) Brian Auger, frontally nude, but with his privates covered by a medallion that depicted the other two members of his band. This side was called Auge. That’s where In and Out came from.

[4] For a good quick chronological Dylan guide, look here.

[5] I didn’t own it; it came into our world courtesy of one of my stepsister Hilary’s friends or boyfriends, who had the admirable habit of leaving a lot of interesting vinyl up at the cottage.

Copyright (c) Jack L. B. Gohn