Love (and Anger) in a Time of Plague: THE NORMAL HEART at Vagabonds

Theater Reviews Page | Previous Theater Review | Next Theater Review

Love (and Anger) in a Time of Plague: THE NORMAL HEART at Vagabonds

Posted on BroadwayWorld.com February 29, 2016

The Normal Heart, being given a welcome revival by Baltimore’s Vagabond Players, is a heck of a play. A thinly-disguised memoir by playwright and gay activist Larry Kramer, it tells of the eruption of the AIDS epidemic in New York City in the early 1980s and the actions of himself and his friends to combat the plague, most notably in founding the nonprofit Gay Men’s Health Crisis. Huge and stuffed with material, with a running time of just under three hours, including intermission, it could stand a little cutting, but there is nothing in it that does not belong. It reminds us vividly of a pivotal moment in the history of public health, of a traumatic loss of lives and of the human connections behind those lives. It also recreates the true death knell, if not the whole funeral, for the complex of arrangements collectively called the closet. At the same time, it never stops being a personal drama.

The central character, Ned Weeks (Steven Shriner), is, to all intents and purposes, Larry Kramer himself. The play follows Ned’s struggles as and after the initially-nameless plague starts killing lovers and friends. In response, Ned not only starts an organization, he advances a philosophical position, and supports that position with determination, and with anger when he is opposed, which is almost all the time.

There are three fundamental points in Ned’s philosophy.

First, gays must stand up and be counted. That is, in order to be counted, to have political power necessary to attract funding for the medical research literally necessary for their survival, gays must first stand up and identify themselves. The closet, Ned maintains, is not itself death, but an exit from the closet is literally required for survival. As the play illustrates in painful detail, this position ran contrary to every arrangement hitherto made by American society, both on the gay and the straight side, for accommodating the large sexual minority in its midst. It was not merely that “confirmed bachelors” like New York’s Mayor Koch refused with hysterical steadfastness to acknowledge what must have been true about them, or to provide any help, recognition or sanction to anything connected with homosexuality, but that almost everyone involved at any level where gays are present and prominent refused to use the label. Consequently, there was minimal pressure for a public policy that acknowledged gays or their needs.

As Felix (Eric C. Stein), Ned’s lover, who covers various cultural matters for the New York Times, points out, he is writing about gay chefs and gay artists and gay designers, etc., but never calls them that. If no one fesses up publicly, it becomes possible for the powers that be, exemplified by Mayor Koch’s henchman Hiram (Ryan Cole) to brush off the relatively modest requests of Gay Men’s Health Crisis for assistance, and for Dr. Brookner (Laura Malkus), who has treated the most AIDS patients of anyone, to be denied federal research funding to help identify the cause of the plague.

Second, Ned refuses to stray from a stance that both gay and straight people must agree that gays are “normal,” that their sexuality is not pathology or reaction to trauma, but one normal way to be human. (The phrase “the normal heart” comes from an Auden poem that conveys that the all human hearts crave “what [they] cannot have, … to be loved alone,” a craving that respects no boundary of orientation.) Ned breaks for a time with his rather supportive brother Ben (Jeff Murray) because Ben, for all his love for Ned, refuses to concede the normality of homosexuality, and Ned reunites with Ben only when Ben comes to assist at a ritual marriage between Ned and Felix, implicitly granting that acknowledgment. (At the time of the play’s premiere in 1985, same-sex marriage would still wait eight years to be legally recognized in any U.S. state. So this ceremony in the play, as younger viewers might not understand, was strictly unofficial and aspirational.)

Going along with this strand in his thinking, Ned has arrived at the view there is something abnormal about the rampant sexual promiscuity, the polar opposite of marital fidelity, in urban gay society of the time. Though, as the play makes very clear, Ned has been an active participant in the fast and loose life of the gay bars and bathhouses, he has come to dislike what all the sex has done to the emotions of those involved, specifically to their capacity for love. More urgently, Ned senses that Dr. Brookner is correct in her perception that all that sex has something to do with the transmission of the plague. Of course, this puts him at loggerheads with almost everyone in his circle, most eloquently represented by his fellow GMHC volunteer Mickey (David Shoemaker), for whom the most wonderful thing about gay liberation has been all the sex. Taking that away would be like depriving him of light and air.

Considering these three themes together, Ned has something to fight about with almost everyone, even those who basically agree with him, Felix and Dr. Brookner. He is impossible to pin down when he fights, ricocheting from one of these arguments to others, whether the transition is logical or not, which helps promote Kramer’s self-aware self-representation as a pain in the ass. But it’s not just Ned; there’s a lot of combativeness to go around. Perhaps the strongest moment in the whole play (the only one during the course of the action on opening night that drew its own applause) is when Dr. Brookner volcanically confronts a government committee over the denial of funding for desperately needed research.

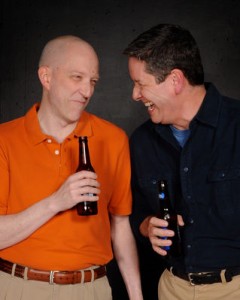

But the play is not all dialectics and windy argument, as important as this is: it also is the love story of Ned and Felix (depicted above in the happy early going between them), the tale of the frayed but still-developing bond between Ned and his brother, and an account of the “band of brothers” that was GMHC, depicted as fracturing at the very moment of success. (The truth was a bit more complicated but in theatrical terms it works well.) And like most great playwrights who turn their attention to public events, Kramer maintains a tight relationship between these stories. Kramer’s artistic control of the huge canvas on which he paints is in the end what makes the play so powerful.

That said, this is definitely a community theater production, both in terms of the acting talent and the stage resources available. Opening night was plagued with flubbed lines, and the scene changes lasted too long, given the minimalist set (by Maurice “Moe” Conn). Still, it was evident the audience came away stunned, just as Kramer intended. Standouts were Eric Stein (whom I’ve praised before in these pages), whose portrayal of a smart man dealing sometimes well, sometimes badly with the fact he is dying of a frightening disease, was spot on, and Laura Malkus, who knocked the tough, wary, and despairing lines Kramer gave Dr. Brookner out of the park. If you want to see a more polished professional production, there is always the 2014 HBO rendering. But the play gains something from being experienced up close and personally.

Bottom line: This is an underproduced American classic, and should not be missed in this live recreation.

Photo credit: Tom Lauer

Copyright (c) Jack L. B. Gohn except for production photograph

Theater Reviews Page | Previous Theater Review | Next Theater Review