The Best Revenge

Theme Songs Page | Previous Theme Song | Next Theme Song

The Best Revenge

You Oughta Know, by Alanis Morissette and Glen Ballard, performed by Alanis Morissette (1995), encountered 1995

Buy it here | See it here | Available on Spotify | Lyrics here | Sheet music here

Living well is the best revenge, goes the saying. By the time Alanis Morissette’s volcanically angry signature song You Oughta Know came to my attention, I’d already chosen the living well revenge for myself, over a year before. The anger that had driven me to choose that revenge was still fresh, though, and my anger was as persistent as Alanis’, too good to let go of even if one could have. And that mattered more than the obvious fact that whatever had provoked her anger was way different from what had provoked mine.[1] That’s why I would drive along with the cassette of her album Jagged Little Pill in my car radio, singing along at the top of my voice —

And every time you speak her name

Does she know how you told me you’d hold me

Until you died, till you died

But you’re still alive

— over and over again.

Paradoxically, I’m not sure I could have enjoyed my anger so much if I hadn’t reached a point in my life when, overall, I was calming down. I had been one to indulge my rages over the years, not only against the bad guys life sends one’s way but against the good guys, my family members especially. By now, though, I was coming to realize the moral imperative of holding my temper better. But temper and rage are one thing; this was different: productive, liberating anger.

In mid-1995, I still had a raging hangover of that anger.

Life as a Square Peg

Over what? You have to go back to what I call the Round Hole Law Firm where I found myself nominally a partner, in 1993. And let me be fair. I owe that firm my gratitude for rescuing my practice group and hence me from the collapse of the law firm that in these pages I have called Funhouse. And they were eventually kind enough to call me a partner. But I was a square peg at Round Hole, a lawyer whose work didn’t really fit any of the practice groups, and wasn’t plentiful enough so that I could constitute myself a practice group of my own. My square peg-ness became more apparent as my designated practice group’s principal client began withdrawing work for various reasons.

Now when you as a firm have a square peg, you can try to make a square hole by finding the person work he or she can grow. And heaven knows, I was doing everything within my power to be a good service partner and justify receiving that kind of help, should they choose to offer it.

They didn’t. Basically, they went to the other extreme.

There were two events.

Despicable

When you are hurting for a “book of business,” the one thing you most want is to develop one. But in a large law firm, the chances are that almost everything that might otherwise come your way falls into one of two forbidden categories: a) already spoken for or b) conflicted out. That is, either one of the people senior to you has already located that piece of business and laid claim to it, or the reason no one in the firm has it is that no one can touch it because of some kind of conflict of interest. It can make trying to market yourself very, very hard. I kept coming up against that problem.

Then, late in 1993, to my delight, something was offered to me that could have been profitable: a contractor’s claim for unpaid work building out some mall storefronts. Since the store chain involved hadn’t paid, my client had a claim against the chain’s surety. As it happened, Round Hole often represented sureties, but not this particular surety. So there was no direct conflict. Recognizing there was still a possibility of an “issues conflict” (where the firm might be required to make contrary arguments on the same legal issue for different clients), I carefully sought the blessing of the lawyers who did the surety work. Again, to my delight, I received that blessing. So I signed up the client.

And then I had to go into the hospital. I appear not to have written in these pages about my back problems. I have them, that’s all you really need to know. And at that point, I had them badly enough so that I needed to undergo surgery, be hospitalized, and take a week or so off from work as well. While I was in the hospital, however, some of the partners who had previously cleared my taking on the construction firm client in the first place fired the client without consulting me. When I got back, no one apologized, or even explained. My assumption is that the same partners who had originally discounted the possibility of an issues conflict had rethought the matter. Still, firing my client behind my back when I was sick in a hospital, a client everyone involved must have known I really needed, was simply despicable.

The Ritual

This was followed closely in time by the division of the profits at the end of 1993. All law firms, except those that are strictly “eat what you kill,” have to find some discretionary way of dividing up the profits. When you need an exercise of discretion, someone has to exercise it, and in most firms, the partners vested with the discretion are the partners with the clients. Not being one of them, I knew no one was going to invite me into that circle. Fine; but I wanted to think that the guys in that committee (I think they were all guys) would use their power fairly. They were the folks mostly entrusted with the firm’s governance, after all, and I was (mostly willingly) trusting them with that as well (even though I had no choice).

The ritual at Round Hole was that each partner would sit down with the committee and justify his or her claim for a share of the firm’s profits. This was an exercise I am sure I would have found humiliating even if I had possessed a large “book of business.” But I tried to keep up my dignity. I was truly proud of my record as a service partner.

It will come as less of a shock to the reader than it did to me that I was not treated fairly. In fact, when the numbers came out, I could see that the members of the Committee had (in my view) paid themselves and their friends remarkably well at the expense of people like me. I had been screwed.

So there I was, screwed because I didn’t have a book of business, and screwed in trying to develop one. Just generally screwed all around.

I realized then that I faced a fundamental choice. No one had said a word to me, but I had been told remarkably clearly where I stood. I could see how the firm’s command structure felt privileged to treat me. There was no reason, given these cold realities, that I should expect anything better, if I stuck around.

Tim and Lou

It may seem incredible that sticking around even appeared an option. And it may not actually have been an option. In light of things that happened at Round Hole later on, I doubt I could have hung on forever. But the option seemed real to me then

Real and horrible. I had seen what that looked like.

One case was a partner I’ll call Tim. At one time, he must have had some self-regard. But he just didn’t have the business, and got by on handouts from others. By now, however, he was treated as a joke by his partners, even by his wife. And then he died. He died without having experienced dignity anywhere in his life for quite some time.

Then there was an “of counsel” I’ll call Lou. The firm had taken his one big case, his dowry, milked it, and then given him nothing back. Consequently he was coming into work each day and doing nothing. And as he told me confidentially, “There is no harder work than doing nothing.” Unlike Tim, he was rescued when an old colleague from before Round Hole invited him into a practice in another town. The last time I saw Lou, he had a spring in his step and a smile I had not seen in years.

So was I going to resign myself to being a Tim (a man without hope) or a Lou (whose hope consisted of waiting for someone to pull him out)? The answer might seem obvious. But actually choosing anything different was a hard decision. True, I had been flirting with variations on the theme of escape for a few years. I had quietly interviewed with other firms (always coming up against the same barrier of no book, despite my credentials). I had tried to do a business plan for going out on my own (but always running up against that same barrier). I might be willing to make a bet on myself, even though I had practically no “portables.” But I had three kids for whose education I was paying at least a share. Making a bet on myself would be forcing a lot of other people to make a bet on me as well.

I could very well have stood poised on the edge of the diving board forever, or, like Tim, walked sadly back to poolside. What decided me to jump? The anger, of course.

No Business Plan for Moses

I was coldly furious at many of the people I was constrained to be polite to as I met them in the office, day after day. They did not deserve my cheery greetings, which were sticking in my throat. I had to take these two incidents as a sign from God; I reflected that Moses could never have had a business plan when he left Egypt either. You had to be crazy enough to count on some parted seas and columns of fire and manna and burning bushes and water flowing out of rocks.

As a wiser Jiminy Cricket might have said, Always let your anger be your guide.

So, at the beginning of January, 1994, I announced that I would be resigning effective the last day of February, and starting my own practice the following day.

Having done one bold and risky thing, I then spent the next two months trying as hard as I could to be careful and provident. I rented space, had stationery designed and printed, bought malpractice insurance, acquired a computer and staged it with carefully selected software, borrowed some starting capital from my stepdad and my father-in-law, ordered office furniture, etc.

As the day approached, it got scarier and scarier. But the anger kept me going. I was damned if I was going to stay subjected to people who had treated me that way. And the way the upcoming division of my work was being handled didn’t do anything to cool me down. It was made very clear that, even though I was the one who had been in nearly sole charge of the railroad asbestos business described in an earlier piece, I could have that over their dead bodies. And mine. (Nothing like someone else’s greed to keep the blood boiling.)

Jailbreak

Of course I got no work done on my last day, Monday, February the 28th. Much of my stuff had already been moved to my new quarters. At the end of the day, a colleague helped me haul the last couple of loads to my car. It all came to a very quiet conclusion.

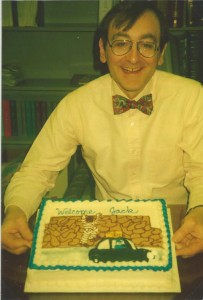

The next day, in my new office, with the new furniture not yet delivered and the new computer somewhat balky, it was not until my landlord, whom I want to thank by name for his many kindnesses towards me – Nevett Steele – called me into the library of his suite where I was subletting space and presented me with a sheet cake, copied here, the decoration of which bears close inspection (click on it), that I suddenly began to have a conviction, not merely a hope, that somehow things were going to be all right.

The next day, in my new office, with the new furniture not yet delivered and the new computer somewhat balky, it was not until my landlord, whom I want to thank by name for his many kindnesses towards me – Nevett Steele – called me into the library of his suite where I was subletting space and presented me with a sheet cake, copied here, the decoration of which bears close inspection (click on it), that I suddenly began to have a conviction, not merely a hope, that somehow things were going to be all right.

And then the phone started to ring. Former colleagues at the big firm referred cases. Old clients turned up with new business. Friends sent friends. People I’d never heard of referred other people I’d never heard of. People I’d applied to for a job sent cases. One lawyer who had formerly been my adversary in a number of matters asked me to represent him personally. To my delight I was making ends meet, and doing better work, too, simply because I was happier than I had been in a long time. I had not budgeted to turn a profit at all in the first year, but I was into the black in only fourteen weeks. I started repaying the parental loans. I and my family never missed a meal. The State Bar Association started responding to my oft-expressed wishes to be involved. Friends from big firms were asking me about my break for freedom, and I could hear a wistful note in their voices.

March 1, 1994, the date I inaugurated my practice, turned out to have been the beginning of the three happiest years of my professional life, when I was entirely on my own. (No aspersions on anything that happened later, mind you.) It was the best revenge.

_______________

[1] There is what they call a cottage industry of speculation over the identity of the original of the unnamed man to whom the song is addressed, which Morissette has been encouraging in a teasing way. But while the song clearly concerns a romantic and sexual breakup, the Wikipedia article on the album tells a different story that may better explain the song’s truly obsessive quality: “Morissette later revealed that, during her stay in Los Angeles, she was robbed on a deserted street by a man with a gun. After the robbery, Morissette developed an intense and general angst and suffered daily panic attacks. She was hospitalized and attended psychotherapy sessions, but it didn’t improve her emotional status. As Morissette later revealed in interviews, she focused all her inner problems on the soul-baring lyrics of the album, for her own health.” The story is told without citation, and I am no Morissette scholar. But it feels right. In either case, whether Morissette was the victim of PTSD from having been threatened at gunpoint or had merely suffered a particularly pronounced case of broken heart, her emotional state was only like mine, not the same. This doesn’t mean her song shouldn’t have spoken to my own situation.

Copyright (c) Jack L. B. Gohn except for cover art