Fresh Production, Unfresh Play: AMADEUS at Center Stage

Theater Reviews Page | Previous Theater Review | Next Theater Review

Fresh Production, Unfresh Play: AMADEUS at Center Stage

Posted on BroadwayWorld.com September 22, 2014

It is extraordinary how differently various plays age. Some may seem like ephemera when you first see them as a child, and still speak strongly to audiences when you are old. Others, ones that seem sturdy, lasting theatrical achievements, grow stale in a generation. Center Stage, in a perfectly good revival of Peter Shaffer‘s 1979 hit Amadeus, has unexpectedly revealed that play to be of the second sort.

How could this be? Surely the mysteries of mediocrity and genius, as exemplified respectively by Shaffer’s antagonists Salieri and Mozart, are as intriguing now as ever. Surely the ancillary themes of patronage and celebrity exert as strong a pull. And, most emphatically, the role of divine providence, if divine providence there be, and the ins and outs of bargaining with God, if there is one, still hold the imagination. What has gone wrong?

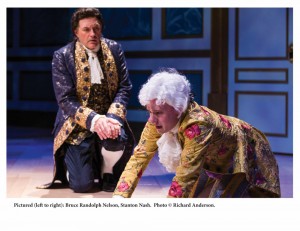

I’m not completely sure. I do have some thoughts. But before I share them, I again must emphasize that there is nothing wrong with the handsome production director Kwame Kwei-Armah has given us, from the amazing two-storey set by Timothy R. Mackabee to the decolletage-heavy, periwig-topped, bustle-bottomed, gilded costumes of David Burdick, to the sturdy performances of Bruce Randolph Nelson and Stanton Nash (pictured above) as Salieri and Mozart, to literally everything else associated with this resurrection of the show. I am convinced that the problem lies with the script itself.

And I think you can sum it up in two words: slow and obvious. The exposition begins with a sort of choral back-and-forth between two Viennese gossips, Venticelli (“little winds”) in 1823, about composer Salieri, who is dying. They obsessively repeat the same words over and over with variations, as if they were musical phrases in a Minimalist composition, evidently to emphasize both the indefiniteness and the widespread nature of talk about Salieri’s impending demise and the possibility that he may have poisoned Mozart thirty years earlier. And all of a sudden we in the audience feel the sinking feeling this may not be as much fun as we’d been expecting. This ought to be moving along. Then we get Salieri sitting in a wheelchair, being arch about what really happened, but intimating that he had a hand in Mozart’s demise. And after a good deal of that, we finally get the story itself, in flashback.

As to the story itself, we learn – well, it would be a very sheltered theatergoer who didn’t already know the gist of what we learn. But the story of why and how Salieri did Mozart in (this is not necessarily historical) is encumbered – there is no other word for it – by Salieri’s narration. Nor is this a “just the facts, ma’am” narration; this is the tortured but ploddingly literal tale of Salieri’s failed relationship with God himself, of God’s betrayal of a bargain Salieri feels God made with him, by giving Mozart a divine talent that should have been Salieri’s. It is also a sort of greatest-hits retrospective of Mozart’s compositions, especially his operas. That’s an awful lot of freight for a single play to carry.

I don’t think it’s insignificant that when Shaffer reworked the script for the 1984 movie, he made it explicit that the mysterious commission for the Requiem that was Mozart’s great final composition came from Salieri himself, disguised as the revenant figure of Mozart’s late domineering father, in hopes that Salieri could steal the Requiem and claim credit for it (a scheme foiled by Constanze, Mozart’s wife). The storyline needed some old-fashioned intrigue and melodrama to stay interesting.

As it is, the play is about using influence and connections to starve a rival artist, a somewhat more realistic but less compelling tale. But I think what mostly resonates less is the God part of it. Have we just become less religious and therefore less inclined to find credible Salieri’s being able to entertain a conceit that he had a deal with the Divinity? Hard to say. But the God stuff seems to be the place where the rubber fails to meet the road, where playwright Shaffer’s own aspirations prove too lofty. And it matters tremendously, because this is Salieri’s play, much more than Mozart’s.

As I find myself saying almost every single time I talk about a play put on by Center Stage, the acting is superb. But as I also find myself saying from time to time, I wish there were a larger Baltimore contingent in the cast, people whose resumes show they came up through the local theater scene. I find myself saying this particularly for two different reasons this time around.

First, it is clear – and this show finishes establishing it, if anyone doubted – that Bruce Nelson has emerged as one of the leading lights of the local professional stage, with this being at least his fifth appearance at Center Stage, and with his turns at the REP, Everyman, the Folger, Olney, and Woolly Mammoth.

Second, we are this month mourning the passing of two actresses who were mainstays of Center Stage in the days when it truly was a local repertory company: Tana Hicken and Vivienne Shub.

There has been much ink, digital and otherwise, spilled (some of it by me) about how Baltimore is emerging as a theater town not only in the development of four professional companies with their own “houses,” but also in new kinds of synergy that are occurring here, among the professional companies but also to some degree with the two academic theater programs in the area and with the community theater scene. But this is one area where much more should be done. Bruce Nelson‘s nurturing to mature artistry by the entire community is admirable, but we need several Bruce Nelsons now. We need fewer imports and more exports with the Baltimore brand on them.

I understand that Everyman is now effectively filling the role that Center Stage used to, local professional company working in repertory. (Well, Everyman and in various ways the Chesapeake Shakespeare Company and Single Carrot.) But as long as Center Stage weighs its casts down with men and women whose experience is heavily laden with Broadway and Off-Broadway, and with regional theater from (to misquote W.S. Gilbert slightly) every country but our own, this local theatrical enterprise is going to have a harder time launching itself and earning the national respect it aspires to.

Just saying.

I promise you’ll enjoy Amadeus. Maybe just not as much as you might have expected. It’s a fresh production all right, but the play itself has gone off a bit.

Copyright (c) Jack L. B. Gohn, except for production photo

Theater Reviews Page | Previous Theater Review | Next Theater Review