Worked For Me

Theme Songs Page | Previous Theme Song | Next Theme Song

Worked For Me

Freedom, by Dave McHugh, performed by Chaka Khan and Michael Rod (1984), encountered 1985

Buy it here | See it here[1] | Lyrics here

Break My Stride, by Matthew Wilder (1983), encountered 1985

Buy it here | See it here[2] | Lyrics here

By the time I was a few months into my divorce, I had made it my business to see quite a few divorce movies, a genre in which the period was rich: Smash Palace, Twice in a Lifetime, An Unmarried Woman, Shoot the Moon, Kramer vs. Kramer. I found them all utterly absorbing. No mystery to it: I wanted to check out as many different artistic takes on what I was going through as I could. Even though I saw them all in the theaters, I also rented and watched them multiple times, completely absorbed. This was my story up there, one way or another.

Expatriate

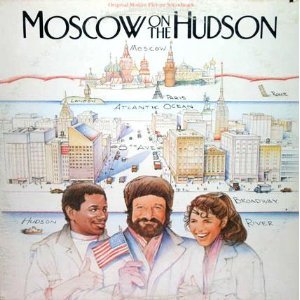

The movie in this obsessed process that affected me most, though, wasn’t actually devoted to divorce. Moscow on the Hudson focused on a rarer subject: expatriation. The thing was, defecting from the Soviet Union in 1984 as screenwriter and director Paul Mazursky depicted it looked an awful lot like the divorce I was going through: the longing to escape, the sense of daring and danger when one did it, the initial high, the practical problems, the unexpected new friends and allies, the bouts of missing the situation one had left, the strain on old family ties, the need to be willing to forge a new identity: all there.

The part of Moscow on the Hudson I rewound and replayed the most was the end credits. They start with Robin Williams as the defector, a saxophonist named Vladimir Ivanoff, as he finishes a letter from New York, where he lives now, to his family back in Russia, summing up the good and the bad, but mostly the good of his new life. The visual behind the voiceover is of Vladimir busking with his saxophone in a park. The song he plays is the first song we got to know him with at the outset when he was a musician in a Russian circus band. In that milieu the melody (no doubt by design) sounded cheerful but superficial. Now, played solo with lots of jazz riffs, it sounds distinctly mournful and much more profound. Michael Rod (the actual musician playing for Robin Williams) leaves pauses between the phrases, which begin to be filled in by singer Chaka Khan, singing a song called Freedom. As the titles fade to a black crawl, Khan’s song merges with Rod’s, and the sax provides continuous counterpoint throughout the titles to Khan’s soulful pop evocation of freedom (political and personal).

Freedom, she sings, I just want to love you. Possibly it’s deliberately ambiguous about whether the love object is another person or just the state of being free. Nor is it clear if the freedom is personal or political. Any way you construed it, it worked for me.[3]

Disco-ey

Another song from that era that always reminds me of that stage of my life was a bouncy, disco-ey piece called Break My Stride, by a near one-hit wonder named Matthew Wilder (this being the one hit). The picture it instantly brings to my mind is of me going around the running track at Baltimore’s Downtown Racquet Club (in later years the Downtown Athletic Club, which I have belonged to, off and on, to this very day). There was and still is a PA system there that plays hits calculated to put you in the mood to sweat, and I can recall hearing that oh-so-appropriate song as I was pounding along:

Ain’t nothin’ gonna break my stride Nobody’s gonna slow me down, oh‑no I got to keep on moving Ain’t nothin’ gonna break my stride I’m running and I won’t touch ground Oh‑no, I got to keep on movingThis is not a song about exercise (though it goes perfectly with that pursuit). The above lyrics are the expression of a woman who has left the singer behind. But the singer has the same attitude:

Never let another girl like you, work me over Never let another girl like you, drag me under If I meet another girl like you, I will tell her Never want another girl like you, have to say Ooooooh Ain’t nothin’ gonna break my strideIn short, this is a breakup song; it’s a song about two people who are moving on in both metaphorical and literal senses.

The Racquet Club was a special place to feel that way. It had opened in a disused-but-then-converted Railway Express Agency[4] shed only a few years before, during the first flush of the Baltimore renaissance presided over by the city’s great cheerleader, Mayor William Donald Schaefer, when the city seemed to have done more than recover from its 1968 riots, and to have become radiant with possibility.[5] Young professionals flocked to the Club but also more established folks; it had quite a bit of singles action, too, at its bar. With all those atmospherics, it was hard not to feel that one was indeed getting on with one’s life rounding that tenth-of-a-mile oval, while being urged on by the bounce of a song that trumpeted above all else a determination to keep on going.

Again, it worked for me.

[1]. This version, notwithstanding it is from the official soundtrack, does not have most of the Michael Rod saxophone interpolations that gave the song so much meaning in context (as described below), but Khan’s voice comes through much more clearly. It sounds as if this version has more of the Richard Perry production that was lavished on the Pointer Sisters’ version (see Note 3 below) than was in the movie too.

[2]. Only don’t view the video before reading this piece; it contains every laughable disco mannerism of that era. Once you see it, you can never hear the piece the same way.

[3]. The movie soundtrack LP is rare and hard to find. In 1985 the Pointer Sisters did a very comparable version (minus the saxophone), produced by Richard Perry.

[4]. I’ve reminisced about the Railway Express Agency a little bit here.

[5]. I’d say that era lasted until the savings-and-loan crisis of 1986 (which ravaged my Baltimore world) and the AIDS scare (which also kicked some of the disco out of straight people as well).

Copyright (c) Jack L. B. Gohn, except for cover art

Theme Songs Page | Previous Theme Song | Next Theme Song