Who You Know

Theme Songs Page | Previous Theme Song | Next Theme Song

Who You Know[1]

Libby, by Carly Simon (1976), encountered 1976

Buy it here | See it here | Lyrics here | Tabs here

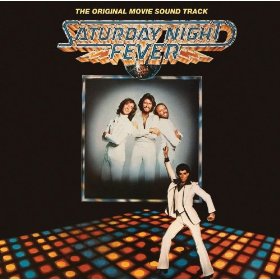

How Deep Is Your Love, by Barry, Robin & Maurice Gibb, sung by The Bee Gees (1977), encountered 1977

Buy it here | See it here | Lyrics here | Sheet music here

The Unmarketable Life

So: What do you do when almost everything you’ve achieved in your life has proven unmarketable? And you’re 26? (See my previous Theme Song piece for details.)

Well, at that age curling up and dying isn’t an option, particularly when you have a wife getting ready to go to law school and an infant daughter. On the contrary, there are two imperatives. The first priority is to find something remunerative to do, something that earns an adult income. And then you have to rethink everything. The second requires more time; it’s a process of discovery.

Job One, the job search, had me knocking on a lot of doors, especially in Washington. I remember more than one hot day near the Mall or up in the Federal Triangle, my white shoes[2] killing me, as I walked from federal office to federal office. I had taken the federal civil service exam (a Maryland one too) and researched job openings as best I could. But no matter where I filled out application forms or left my resume, I got nowhere. To the best of my recollection, nobody ever interviewed me for anything. I also tried my hand at journalism, and had some little bits of success. But what that brought in could never have been mistaken for an adult income.

Following the Mantra

That was the unbelievable thing: I had so much knowledge and still didn’t know enough about how the world worked to land any kind of job interview. I grudgingly acknowledged at last a mantra of my father-in-law’s: “It isn’t what you know, it’s who you know.” So I started thinking about the whos I knew.

One of the “whos I knew” was an administrative law judge with the National Labor Relations Board, my mother’s oldest friend. ALJ Jo lived in Alexandria, Virginia, an hour away. I called her up on a Thursday and laid out my situation. She told me she’d see what she could do, and that I should call her back the following Monday. When I did, I found she had come through: she could make me either a parole officer in Northern Virginia or a court reporter in Washington. I had never heard of court reporters, and asked her what they did: make transcripts of legal proceedings, she said. That sounded pretty good to me, and then too Washington was closer than Northern Virginia, so I told her I chose that one. Fine, she told me, and promised to have the contact information the following day.

And indeed she did write me the following day, with word that the boss of this court reporting agency, Roy, was expecting me to call him. Things moved quickly after that. Roy was more than willing to see me. (I soon worked out that his company had the prime contract on reporting all administrative hearings of the National Labor Relations Board, and doing favors for the ALJs was a concept he was wide open to. It wasn’t what you knew …) I visited his office on Seventh Street, SW, in the aptly-named Reporters Building. And, on May 18, 1976, a date I vowed never to forget, I walked out of the Reporters Building with my first grown-up job offer, to start in late summer. It wasn’t at all what I had expected to be doing, but it was a respectable living wage. And that was enough for the moment.

Remedial and Basic

While awaiting the beginning of my training, I paid heed to another parental prompting. There I was, the son of an economist teaching at a graduate business school, and I had never had the slightest training in either economics or business. It think it finally occurred to me that perhaps my inconveniently unworldly ways might have owed something to that deficit in my fund of knowledge. So I signed up for courses in both subjects at Towson State University, as it was then called. Introductory Econ and Bus Ad rubbed my nose in how little I knew – and delighted me with a flood of new insights into how the world worked. It was also nearly my first experience of higher education at a non-elite institution – and I liked it just fine. There was something about the lack of pretension that I found liberating.

Come the end of the summer, I was ready to start training. The technology was called voicemasking, a technology so passé 40 years on I can’t even find a photograph on the Web of the essential item: a big plastic sound-deadening mask you draped over your mouth and nose.[3] Inside the mask was a microphone into which you repeated (with stage directions) everything that was said in a legal proceeding. A wire would carry your voice feed to a tape recorder; later you’d use the resulting tape plus a backup tape of the proceeding itself to produce a transcript. The central skill, talking while listening, took a week or two to master. I believe I was ready to go in about a month.

It was a strange job, sometimes exciting, sometimes boring and frustrating. I never got to take a trial (there were official court reporters for those) and only got to take a deposition once (because those required notaries, and no one invested in making me one), but I got to do practically everything else once could think of.

It Couldda Been Worse

There were plenty of the NLRB hearings (fights over unionizing or de-unionizing workplaces). And those could take you anywhere: Norfolk, Baltimore, Scranton, Williamsport, sometimes even as far afield as Canton, Ohio (that hearing canceled on me after I drove a long way in a rented car in a snowstorm). Mike, the dispatcher, would say, in a whiny drawl: “Make like a bird and go to Pittsburgh,” and off you’d fly, all travel paid, with a decent per diem. If you liked travel for its own sake, and sometimes I did, that was great. Of course, if your wife had commitments that were inconsistent with childcare, it could be a problem.

But it wasn’t just NLRB; we had all kinds of federal agency hearings: FDA, FCC, Treasury, Postal Service. These were at all levels: from arbitrations to commission-level deliberations. Most of those were in Washington, though I remember one FCC matter that took me to Connecticut for three days.

The most interesting matters tended to be the grand jury proceedings; in those days all felony indictments in D.C., both federal and “state,” were handled by Assistant United States Attorneys, sharp and larger-than-life young lawyers. You got to see a panoply of all different sorts of cops (D.C. Metro, Park Police, Capitol Police, FBI, BATF, Secret Service, railroad police, postal police) and all sorts of bad guys, though never the bad guys they were trying to indict. I remember particularly one pimp who must have been testifying against some other bad guy; the pimp had an utterly magnetic personality. He was funny, appealing, charismatic. You could hardly help wishing you could have him as a friend.

And the lawyers were frequently very interesting too, particularly when they worked out that I was the product of the kind of education that made me somewhat atypical – though I quickly learned that there was no typical, when it came to court reporters. (My next Theme Song piece will be about a colleague who proves that point.)

Also, Washington could be exciting. It wasn’t all shuttling on underground trains among Union Station, the Reporters Building, the Federal Triangle, and Judiciary Square. I was a runner then, and frequently would put on my running shoes to head up to the Mall for lunch hour; I can remember one snowy weekend day when I had the Mall and the Capitol to myself, and ran up the stairs, Rocky-style, breathing the chilly air in exultation. I could head over to the areas near the National Portrait Gallery for shopping at Hecht’s and (I think) Garfinckel’s. And at Union Station itself there was excitement in a huge installation, just opened for the Bicentennial in the main hall, a huge pit with an array of video screens that could work in tandem or separately to hawk the attractions of Washington to arriving tourists. I remember that the music which accompanied the show (I must have seen and heard it all dozens of times) was peppy and catchy, and included plucked bass notes that reverberated beautifully in the marble halls. And of course this was the dawn of the Jimmy Carter presidency, when, for a liberal, all things were being made new – or so it appeared.

At times I felt like saying: Take that, Hopkins! I may not be teaching literature, but I’m out here in the big exciting world, so there!

It Couldda Been Better

At the same time, it was very lonely work. You were seldom in the same place from one day to the next. You rarely saw your fellow-reporters except back at the company offices if you were transcribing grand jury notes (you weren’t allowed to take them home, unlike notes from administrative hearings). And when doing that you were in a long dark gallery where people from sister companies, not even your own company, were likely to be your only neighbors. It took me away from my wife and daughter and plunked me down in a different city, either Washington or somewhere else, almost every day. And I would always be a functionary, never a star like the lawyers who strutted and preened and growled and fought. Not even like a witness. And, let’s face it, going to Scranton or Allentown or Salisbury may have had some charms, but it was not glamorous traveling.

So I had “theme songs” for both moods.

For the more wistful one, there was Libby. One day in October of 1976, not too long after I’d started, after taking down the proceedings of a Food and Drug Administration toxicology conference on new animal drugs, I found myself in a record store on the Rockville Pike, and I picked up Carly Simon’s latest album, Another Passenger. The album title was a quote from the most important song on the album, Libby,[4] it resonated powerfully with me.

As I’ve already partly disclosed, Simon had always seemed to me like a spokeswoman for my exact cohort. Well, my exact me, actually. When I’d been doubtful about getting married, she’d been doubtful about getting married. When I’d warmed up to the attached state, so had she (I Haven’t Got Time for the Pain). And now she was getting restive and looking for escape to new climes. Well, so was I.

You could argue that though I probably thought the song was about me, it really wasn’t. And on the surface, you’d be right. Obviously, for a big star with serious money to get restive and want to visit another place was different from me wishing I didn’t have to go to Scranton. Also, the song is very feminine: a man would not have written:

If all our flights are grounded, Libby, we’ll go to Paris Dance along the boulevards And have no one to embarrass, Puttin’ on the Ritz in style With an Arab and an heiress. Libby we’ll fly anywayThe attitude is female and privileged. Finally, the song is about friendship as well as escape. As Simon wrote on her website: “The song … is about my relationship with a woman who used to be a very close friend.[5] The hard times became funny in our mutual observation of them. We got each other laughing over the pain.” I wasn’t having friendship highs or lows.

At the same time, the obvious experience of recent pain Simon’s lyrics evoke was mine as well, and the desire to run away.

Crossing the Bridge

In a way, the court reporting was running away too. Maybe Scranton or Norfolk or Dover wasn’t Paris, but then again it was not Baltimore, the scene of my humiliation, either. And if reporting wasn’t the life I’d chosen or envisioned, it wasn’t always so terrible.

That kind of thinking was what caused me to glom onto another “theme song” for the moments that felt better. That was How Deep Is Your Love, by the Bee Gees, from the Saturday Night Fever soundtrack. I can’t tell you exactly when I first heard it (obviously shortly after September 24, 1977 when it was released), but I can tell you with great precision the moment it was permanently associated with a picture in my mind, about 8:30 a.m. on Tuesday, October 18, 1977. On that pleasant early fall day, I was driving along the eastbound approaches of the Bay Bridge,[6] which leaps over from the military, governmental, and sailboating purlieus of Annapolis to Maryland’s agricultural Eastern Shore. I was headed for an NLRB hearing in Easton, MD. As you move along those bridge approaches, the Bay appears to your right, and, if you can spare a glance from your driver’s focus, you can frequently make out large vessels standing in the roads making towards or away from the Bridge. From your vantage point you are going quickly and those boats have all the time in the world. For some reason, that is a pleasing and calming prospect. And this was a nice clear morning, and there were the boats – and there were the Bee Gees on the car radio.

Now it’s reasonable enough to argue that the lyrics are not so peaceful, and betray the singer’s insecurity in his woman’s love.

And you may not think I care for you When you know down inside that I really do And it’s me you need to show How deep is your love? (how deep is your love?) I really need to learn.But the music simply overwhelms all that. The limpid splotches of Fender Rhodes piano reverb and the slowly-developing quiet harmonies of the Bee Gees’ voices are all about the kind of all’s right with the world security you can feel when you see the boats out in their channels, and you’re off about your business. Impossible at a moment like that not to think of life as a gradually-unfolding adventure. I was going to make a transcript people depended on to reach decisions that governed their work lives. I was earning some real money

It may have had some impact on my affect at that moment that I was beginning to get ideas about the next stage for me. But that’s a tale for later.[7]

For now (or then), I personally was not someone who I knew anymore. But I was wanting to make my acquaintance.

[1] Yes, friends, I’m aware it ought to be “whom you know.” Read on and discover why the solecism.

[2] I had no fashion sense then. But to be fair, neither did a lot of folks. The shoes in question were kind of patent leather-ish and cruise-y. It’s possible (though I think not probable) that those shoes and other sartorial choices turned off some of the gatekeepers who might have given me real access to a job or two.

[3] Nowadays there are still some voicemasks in use, but they don’t cover your nose, and even in this healthier format (you wouldn’t be inhaling nearly so much in the way of vinyl fumes), I get the impression they are not much relied upon.

[4] Obviously, in this assessment, I take issue with the verdict of the Rolling Stone reviewer, who called it “an overlong banality.”

[5] The woman in question was Simon’s friend and sometime collaborator, singer/songwriter Libby Titus. According to her Wikipedia entry, she came from money the way Simon did, and knew and had liaisons and/or marriages with all kinds of interesting people. It seems likely from the commentary in various places that she and Simon must have had some kind of falling out, though no one quite says that.

[7] A tale for nowhere in this blog is the blockbuster Saturday Night Fever album on which the song shortly afterwards came out (premiering in November). Though I liked a lot of the songs, I never bought or took to the album (though I did tape it from the Baltimore County Public Library’s collection one day). And I never was a devotee of the movie, either. What can I say? I was neither Karen Gorney nor John Travolta.

Copyright (c) Jack L. B. Gohn, except for cover art.