Music in the Dark

Theme Songs Page | Previous Theme Song | Next Theme Song

Music in the Dark

Capricorn: The Uncapricious Climber, by Zodiac (1967), encountered 1968

So Many Stars, by Alan and Marilyn Bergman and Sergio Mendes, performed by Sergio Mendes and Brasil ’66, sung by Lani Hall (1968), encountered 1968

Buy it here | See it here | Lyrics here | Sheet music here

Sometimes darkness makes the music more intense, especially music about things you can only see in the dark. This one is about that experience.

But first a necessary preliminary. I wrote once earlier on that there were going to be places in these memoirs where I would elect to be silent about things I remember. Now we reach the principal one. It was at this point that I met the woman I would marry – and divorce. This is not her story, and I have too much esteem for her to invade her privacy even to tell my own tale. I cannot simply give her a pseudonym as I have done with some of the other people I’ve been talking about in these pages; the world knows of our connection, and we have children and grandchildren in common. Hence I shall call her only S., and tell those parts of my story that involve her in such a way as to leave most aspects of her history and personality respectfully to one side. This constricts me a little, but there still remains plenty to tell within those boundaries. All you need to know to start with is that we met as fellow-students at the University of Pennsylvania.

A Not Terribly-Clean Rug

That said, I’ll hustle you, gentle reader, past the preliminaries, and dump you on the not terribly clean rug in the front room of an apartment on Walnut Street, in a building that no longer exists.[1] There are four of us either lying on the rug or sitting on the grungy couches: me, S., and my roommates Jim and Elliot. It is my sophomore year. We call the apartment house Graudensville in honor of our heavily-accented landlord Mr. Graudens. Let me say this gently; Mr. Graudens does not run a first-class establishment; this is a student tenement. The furniture and the rugs come with the apartment, and they look as if they have come with the apartment for a good long time. There are three guys living here in an apartment designed for two.

In my memory, it is daytime but the curtains are drawn (nothing to look at but an airspace between rowhouses anyhow). The lights are low or out. Music is playing.

In years to come I shall look up my roomies’ whereabouts on the Web, and find that Jim has become a lawyer in Youngstown, and Elliot a musician and political activist in suburban Philly. You might think that as a future lawyer with a giant music obsession, I’d really hit it off with each of these guys. But not so. We haven’t bunked down together out of any great interest in each other; we were simply cast out of the men’s dorms by the University’s lottery and had to find flatmates quickly. But being stuck together means it is to our mutual advantage to try to find things to do and enjoy together. Clearly music is our best bet.

Elliot, the future musician, appropriately has the best equipment. I myself am the proud owner of an Ampex tape deck by this time (I think another present from my father, who (as recorded in an earlier entry) gave me my core hi-fi components a few years before).[2] Elliot has either a better Ampex or a TEAC, which is coming to be known as the gold standard of reel-to-reel decks at this point. We hook the two up in series and fell like the kings of audio.

Later no one will be likely quite to grasp the importance of a tape deck. In this era before ripping of CDs and downloading of tracks from questionable sites, it is the only way to get music for free without actually shoplifting – which means it is the key technology in sharing music.[3] Elliot has a lot of cool stuff on reel-to-reel. Elliot also has some pretty cool records.

Psychedelia for Straight Kids

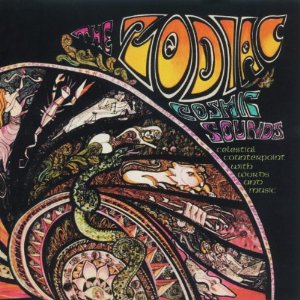

We’re listening to someone else’s record at this moment, one that I’m almost certain belongs to Elliot: Cosmic Sounds by Zodiac. It is a reflection of the time that the cover sleeve could also be read to enclose an album called Zodiac by Cosmic Sounds. And there’s no reality-based context to settle the matter. This is an album all about the Zodiac, and there is no real-life group or act called Cosmic Sounds. So it’s just as plausible either way.

On the front of the cover is a trippy distorted zodiac, so we know this is true psychedelia. On the back is written in hot pink “Must be played in the dark.” And so, following the instructions and the ethos of the era, we close the curtains and douse the lights. This is the time of psychedelia, and we obey. Perhaps there will be revelations in the dark that light would interfere with.

How to describe the psychedelic years to an audience that was not there? “Psychedelic,” initially a technical term for a class of recreational drugs, has come to mean as many things as “hip-hop” will later do. It is a drug style, but also an art style, a music style, a set of social and political views, and two or three fashions in clothing. It says something about the breadth of the label that of the four of us sprawling attentively in the dark, none of us is on drugs. No, not even pot. Yet this is a psychedelic moment for us anyhow.

The record is unique, and perfect of its sort. I quote the Richie Unterberger reissue liner notes, reproduced in the informative Wikipedia article on the album:

Divided into 12 separate tracks, one for each astrological sign, it appeared just as both psychedelic rock and astrology itself were coming into vogue in the youthful counterculture. In some respects it was similar to other instrumental psychsploitation albums of the time, with a spacy yet tight groove that could have fit into the soundtrack of 1966 Sunset Strip documentaries, played in large measure by seasoned Los Angeles session musicians. In other respects, it was futuristic, embellished by some of the first Moog synthesizer ever heard on a commercial recording, an assortment of exotic percussive instruments, and sitar. The arrangements were further decorated by haunting harpsichord and organ, along with standard mid-1960s Los Angeles rock guitar licks. For those who took the astrology as seriously as the music, there was the dramatic reading of narrator Cyrus Faryar, musing upon aspects of each astrological sign in a rich, deep voice without a hint of irony.Here, by way of example, is a part of the lowdown on Capricorn: The Uncapricious Climber:

Eight notes scale an octave. Master the scale and you master the score. Uncapricious Capricorn captures each note, holding it tight until it surrenders. The mystery of music can meld into black and white, then dissolve into grey. Capricorn, convinced, can make grey glisten like white onyx.I don’t think any of us, in the language of those album cover notes, “took astrology as seriously as the music.” But the tour of the varied personalities associated with the astrological signs was entertaining, the music was definitely trippy, and there was something cool about lying around as if we were drugged, even if we weren’t. I think that little snapshot is quite indicative of the way that good middle-class kids of that era made their peace with the ethos of free love and drugs which fueled what was coming to be called the Counterculture.[4] We were all Ivy Leaguers, for heaven’s sake! Three future lawyers and a musician/politician! And yet we were all as sober as judges[5] (give or take a few swigs of Mateus),[6] giving a respectful listen to what was meant to be a drug experience-like trip based on a mythos none of us had the least belief in!

It was the fashion of the times.

Straightness for Psychedelic Kids

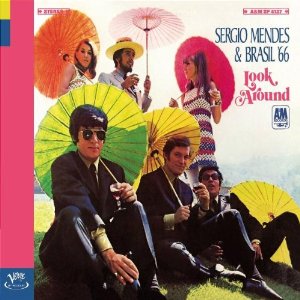

How firmly we had one foot planted in the world of Woodstock (set to happen in about ten months) and the other in that of our parents can be gleaned from another star-focused song on a different record I also recall us listening to in the dark. This LP was a contribution from me: Look Around, by Sergio Mendes and Brasil ’66. Now, despite the candy-colored scheme of the album cover, by the standards of the time, this was square music.

I’ve already written about my infatuation with Brazilian-inflected music, Jobim and the Tamba 4. That stuff was pure and exotic enough to be cool. Mendes was a different story, unique in the Brazilian Invasion, having immigrated to New York in 1964, and having started a quartet (a quintet on records) called Brasil ’65, which was really a jazz outfit with a strong Brazilian accent, then replaced it with a pop sextet he called Brasil ’66, in which half the personnel were U.S.-born. By compromising his Brazilian-ness this way, he could never be exactly cool, but he certainly was popular.[7] Partly it was the great A&M Records covers, which looked almost good enough to eat, partly it was the equally glossy production inside.

Look Around, his third Brasil ’66 album and by far his most pop one to that time, excelled in both departments, and went to Number 5 on the charts. But the songs were the main thing, including the two big hits from the album, the remake of Bacharach and David’s The Look of Love from the Casino Royale sendup movie[8] and the title song, Look Around. These are finely-crafted pop-delivery devices, and we all appreciated them.

Steady Forecloses Possibilities

But the song that really got to me was So Many Stars, a lovely collaboration of Mendes with lyricists Marilyn and Alan Bergman,[9] who were probably twenty years older than the people who had put together The Zodiac, and had first broken big writing for Dean Martin and Frank Sinatra about a decade before. And however swinging Sinatra appears to members of my generation now in posthumous refurbishment, he was suspiciously, well, old to those of us who were teenagers in 1968. So this piece was right on the edge of what we would all have been comfortable listening to – together, anyway.

So Many Stars spoke to me. Reflect: I had my first real girlfriend, after having dated a lot – admittedly, I had wanted a real girlfriend for the longest time – but I was comfortable dating, while I had no experience with being anyone’s steady. So you can imagine the effect of lyrics like these (especially as served up on a lush bed of strings orchestrated by Dave Grusin):

The dawn is filled with dreams[10] So many dreams which one is mine One must be right for me Which dream of all the dreams When there’s a dream for every star And there are oh so many stars So many stars The wind is filled with songs So many songs which one is mine One must be right for me Which song of all the songs When there’s a song for every star And there are oh so many stars, so many starsI was experiencing elation at having found someone so interesting who did me the great compliment of reacting to me the same way. But at the same time, I was aware that I was foreclosing other possibilities in a world full of them. And of course I had the recent history with Carolyn, described in the preceding piece, to just exemplify what I was surrendering. This song spoke wistfully to those very misgivings.

What To Do About Misgivings

In retrospect, where everything is crystal clear, I can say that I should have paid more attention to those misgivings, that a person feeling that way was not ready to settle down, even to the extent that going steady was settling down, especially at such a young age, and even more especially if the person was afflicted with a Catholic moral seriousness that fails to recognize how often sex should not be cause for commitment. But what I was telling myself at that stage was that life was full of tradeoffs, and that I’d be experiencing some kind of emotional confusion no matter what “star” I happened to be choosing. In other words, I was feeding myself the wrong kind of adult wisdom.

I should have listened closer to the music in the dark.

[1] 3923 Walnut Street, an address which no longer exists; I believe the site has been incorporated into larger buildings not once but twice in the intervening years. If memory serves correctly, the mesne structure sited a movie theater exactly where our house had been.

[2] Here’s a photo of me with the deck a year or two later.

[3] In retrospect, it was a very unsatisfactory one. You either had to use fairly short tapes, on which one or two stereo albums might fit, or monstrous ones, that would accommodate typically five and a fraction LPs, leaving you with tough calls between economy (tape only part of the sixth album?) or completeness which created its own form of incompleteness (leave part of side two of the tape unoccupied). The reels were all too bulky, so you were tempted to go with the larger ones, but then you had serious retrieval problems, figuring out where your music was on the reel. You did have access to a sort of capstan odometer, and you could and if you were serious pretty much had to note down readings for starting and ending albums carefully, or you would condemn yourself to hunting around, starting and stopping over and over again, when you wanted to find anything but the first album on the tape. Moreover, tape deteriorated with time. It could stretch, warp, break, or flake. But in those days, it was the best you had. And if, as Elliot and I did when we set up our machines next to each other, you had two of them, you could make tapes of tapes, rearrange the sequence of tracks, and do interesting things with the echo effect. You definitely had something.

[4] Per Wikipedia, the term Counterculture was coined by Theodore Roszak, given currency by his book The Making of a Counter Culture: Reflections on the Technocratic Society and Its Youthful Opposition, which was published right about the time I’m speaking of.

[5] As a lawyer, I’ve often wondered where that expression came from.

[6] Mateus Rose was a staple of college life in that era, at least in the circles in which I ran. I find it almost undrinkable now.

[7] He’s not necessarily so popular in the second decade of the Twenty-First Century, but he has certainly regained his authenticity, at least periodically, and his cool. There’s nothing you can say about his album of collaborations with younger musicians from his homeland, Brasileiro (1992), except “Wow!”

[8] James Bond fans know the story. Casino Royale, the book (1954), didn’t end up in the hands of the Saltzman-Broccoli team which had bought up all the other James Bond movie rights (except for Thunderball, an even more complicated tale). Casino Royale fell into the hands of Charles K. Feldman, who turned it over to much of the same creative team that had given the world the wonderful and more-than-slightly mad What’s New, Pussycat? (1965). Casino Royale, the 1967 movie, was not so wonderful, but, like Pussycat, boasted music by Burt Bacharach, including the indelible Dusty Springfield performance of The Look of Love, which has subsequently been recorded by every musician under the sun. Sergio Mendes and Brasil ’66 performed their cover of that song at the 1968 Oscars.

[9] The Wikipedia pieces on Marilyn and Alan Bergman are helpful in getting a sense of their world, but a better evocation of their definitely pre-60s ethos (notwithstanding their continued, if not greater commercial success after the 60s) can be gleaned from this 2007 Terri Gross interview.

[10] Yes I know many of the published versions of the lyrics show the line as “The dark is filled with dreams” (which would actually fit better with the theme of this piece). But my ears are not crazy; Lani Hall sang “dawn” on this album, as did Natalie Cole or Sara Vaughn in their respective versions of the song. And the sheet music referenced above confirms what I hear.

Copyright (c) Jack L. B. Gohn

Theme Songs Page | Previous Theme Song | Next Theme Song