School’s Out: Night in the City

Theme Songs Page |Previous Theme Song | Next Theme Song

School’s Out

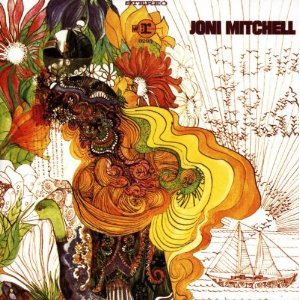

Night in the City, by Joni Mitchell (1968), encountered 1968

Buy it here | See it here | Lyrics here

And just like that, my exciting first year of college was over. True, there’s always a relief in getting to the end of a semester. But I don’t think I was particularly eager for it to end. I was enjoying being a collegian, even enjoying my studies, challenging as they were.

I wish I could write more fully about my classes, the one topic from that year I haven’t touched on in these musical memoirs. But my memory is selective, and my studies have largely been selected out. And in any case, I don’t have music that specifically triggers memories of my studies, not that year anyway. I think it’s safe to say, though, that I knew, coming out of that year, that I was going to be an English major.[1] And there was no doubt that, in my mind at least, I’d worked as hard as I’d played. This equivalence would not have satisfied my demanding mom, but it suited me.

A Little Bit of Coping

Piecing together the few documentary clues that give me dates, I believe I finished up on or about Friday, May 10. But being off duty required a little bit of coping. My parents couldn’t come and pick me up until the following Friday. There were two reasons for this: they had their own classes to teach during the intervening week (and indeed for a week or two thereafter), and they wanted to be in Baltimore that following Friday for the 25th reunion of the Johns Hopkins University Class of 1943, of which my stepdad was a member. So obviously I had to stay East somehow for a week.[2] I actually had one reason of my own, which was a philosophy paper I needed to finish, a paper which, thankfully, my professor[3] let me hand in late.

The Penn dorms had closed, however. That meant I had to find someone to put me up, or perhaps, better said, to put up with me. I have no recollection of asking or being invited, but somehow I ended up staying with Steve, a classmate who lived in Northeast Philadelphia, son of a dentist (who, if the Web is to be believed, now practices dentistry himself). At that time it was a love of poetry that drew us together. We had talked about rooming together sophomore year, but for whatever reason, that didn’t happen.

I wrote a friend about that week: “Their place and food are lovely, not to mention [the family] … His mother urges food on me – ‘Force yourself!’ she says. My beard put her off at first, but she’s figured out I don’t mean anything by it.” (This in an era when beards signaled political dissent, and the dentist dad was of the generation forged in the patriotism of World War II – as a soldier he had been part of the liberation of the first concentration camp discovered. I actually got rid of the beard while staying at their home.)

Joni Wasn’t Packed

Most of my stuff was packed away in the trunks for Railway Express, but I know there was one album that wasn’t: Joni Mitchell’s Song to a Seagull. Well, at least that was the name at one time; it gets a bit fuzzy now.[4] Whatever it was called, it was stunning. Of course there’s nothing original to be said about Joni Mitchell these days, but that stunning voice and those original chords and those poetic confessional lyrics were like nothing most of us had heard then. I can picture sitting in Steve’s parents’ front room and playing it when I probably should have been finishing that Philosophy paper.[5] I must have played it enough so that two weeks later, writing Steve, the first thing I did is mention the album in a way I would only have done if I had known him to be as familiar with the order of the tracks as I was. There’s a phrase in one letter that suggests we may have been listening to Steve’s copy.

My guess is that sensitive young women of that era responded more to the songs on the album about how tough it was to be female and sensitive in New York or about the liberating influence of the seaside. My favorite, though, was the most masculine song on the record, Night in the City. In the comments with which Joni prefaces her performance of the song the previous year (in the video hyperlinked above), she intimates that it was inspired by impatience with a roommate who was taking too long to get ready for a night on the town. But the real subject of the song is simply how exciting the big city is at night.

Night in the city looks pretty to me Night in the city looks fine Music comes spilling out into the street Colors go flashing in timeAnd what really made the song for me was Steve Stills’s slightly funky bass, which made that one song sound much more like rock and less like folk than anything else on the album. Cities rocked, and the bass line confirmed it.

Well, my whole freshman year had confirmed it too. I might have been a bit homesick for Ann Arbor, but downtown Philly, on one’s own, was an intoxicating place to me. And now I was somewhere else. For the moment, I was in a quiet, comfy home in suburbia, awaiting going back to a college town for the summer, stuck finishing a paper. To be sure, I was going to find ways of having fun. But it wasn’t going to be the same.

Encountering Baltimore

Come that Friday, I trained down to Baltimore, my first real visit to the town which, though I didn’t know it, was where I’d spend the biggest portion of my life later on. My parents had flown into Philadelphia and were supposed to have caught a shuttle flight to Baltimore, but their flight was canceled, and they too had to take the train down, a later one. In consequence of this delay, I checked into their Baltimore hotel room some hours before they did. Talk about none of us knowing what we were getting into …

The Baltimore my parents thought they were visiting had just been given the coup de grace, though the dying would take years. After the Martin Luther King assassination on April 4,[6] the town had been plunged into eight days of riots, which any Baltimorean can tell you changed everything. The town was in for years of sliding downwards, losing corporate headquarters, heavy industry, white citizens, pro sports teams, and civic pride. While my folks had been there in the 1940s, it had been a genteel Southern town (which was great if you happened to be white and genteel like them). It was never going to be like that again.

By the time I turned up on the town’s doorstep on May 17, law and racial order had been restored, and I don’t think I saw any of the destroyed neighborhoods – of which I later discovered there were plenty. But another source of civic chaos had just erupted which would stand in for it. This was Preakness weekend. And we were staying at what was then called the Sheraton Belvedere, a faded dowager of a Beaux Arts hotel that was being respected by the party-hearty race-goers in about the same way Blanche Dubois was respected by Stanley Kowalski. There was constant yelling and running in the halls, raucous laughter everywhere – and a couple I’ll call Drew and Lacy.

I think Drew was a college pal of my stepdad’s. In my recollection he was a southern-fried lout, and his wife made some nasty insinuating remarks about my status as stepson, not son – and insinuated accurately, but as if this did me some discredit, that I was partly of Jewish heritage. I think there were also some arch comments about Mother being markedly older than my stepdad. I don’t know what my stepdad was doing being friends with such lowlifes. But they seemed to fit right in with the overall picture at the hotel that weekend.

I saw some of Hopkins too, but I really don’t remember it. What really sticks in the mind was getting off the bus on North Charles Street at Hopkins, off the campus. It was hot and dusty, and the street seemed too wide (I hadn’t yet learned to allow for the subtraction of the trolleys which had shaped so many urban thoroughfares and then disappeared from the scene.) I remember thinking that this was a much less entertaining place than Spruce Street running by my dorm at Penn. If only I’d remembered that perception later! As dull as this stretch of Baltimore was, it got duller in Ann Arbor, to which I soon returned.

Shortly after my return, I wrote a friend that I’d visited a men’s clothing store, where I was told they’d had their slowest Thursday, Friday, and Saturday in the store’s history, seriatim. Of course, this was the nadir, before the summer session started. Things did improve a little as the summer went by. And I had all the leisure I wanted to try for a second summer to finish my novel.

The Exciting City Night

But there was no doubt that I wanted to be back in that exciting city night that Joni had sung about:

Moon’s up, night’s up. Taking the town by surprise. Stairway, stairway, Down to the crowds in the street. They go their way Looking for faces to greet …Well, I’d be getting my shot soon.

[1] An excerpt from a letter to my mom and stepdad in April 1968: “But no matter what I do, I can’t digest French idioms, or petty details about the Baroque synthesis, or what species of brachiopod was dominant during the Permian. I can’t even properly assimilate too much of what I moderately like. And the frightening other side of the coin is that I can spend endless amounts of time doing things I really like, like English, like writing poems, like reading newsmagazines, like Penn Players. This indicates that my control of my powers of concentration is just about nil. And this results in lower grades.”

[2] Or at least it seemed obvious to them at the time. Given that I ultimately flew back in to Michigan separately from them, and that my stuff went back by Railway Express, I’m not sure that there was any obvious necessity for me to stay on the East Coast for that week. Maybe they really wanted to have me at their reunion, but I’m almost absent from my mom’s diary entries covering the event. I think it was just the kind of thing parents of college kids do: not quite reckoning with how independent the kids have become.

[3] This was Robert Solomon, perhaps my favorite professor at Penn. I ended up taking three courses from him. And the day Allen Ginsberg came to talk and read at Penn, he sat in on Solomon’s class, two rows behind me.

[4] The name was spelled out in flying birds in Joni Mitchell’s hand-drawn cover art, pictured above. AllMusic indexes the album under that name. Yet the spine shows only Joni’s name. And Jason Ankney’s biography of Mitchell on the same website calls the album “self-titled.” Don’t ask me how to resolve the contradiction; I only work here.

[5] It still wasn’t done when I left Philadelphia, and I don’t think I finished it for another week. Thankfully, this episode of procrastination was kind of a one-off, and was not going to be my way with school work generally. As a student, a writer, and a lawyer, I generally get things in on time. Call this more of the adjustment to the rhythms of college than a portent of things to come.

[6] From a letter to my parents on April 9: “Shortly after the news got around, the black students on campus gathered in front of the Library, huddled around a transistor radio. I joined them for a while, but I had work to do. Later the black students walked over to the ghetto, to be with their people. The next day they held a really frightening vigil at noon. After some gospel singing, the small crowd of blacks and much larger one of whites was treated to a series of Black Power harangues. I got upset. I don’t like being called ‘honky’ any more than a black likes being called [n-word]. One of my black friends got up and spoke, and I didn’t like the change in him at all. Still the last two speakers addressed the larger crowd of whites, warning them not to take everything said literally. They said that the Negro is a very emotional person, and that this anger is his natural response, but that militancy is just one approach and that nonviolence and moderation were still at leas as valid as militancy.” A confusing time! And no one realized that it’s insulting to talk of “the Negro” or for that matter “the white man.” Not the speaker I quoted, and not me, at the time.

Copyright (c) Jack L. B. Gohn, except for artwork