A Brief Glimpse

Theme Songs Page | Previous Theme Song | Next Theme Song

A Brief Glimpse

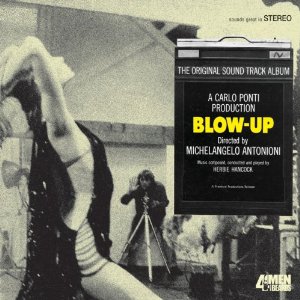

Main Title to Blow-Up by Herbie Hancock (1966), encountered 1967

Buy it here | See Bobby Hutcherson cover of music with stills here

My mother’s diary reports that I first saw Blow-Up on Saturday, February 25, 1967 with my friend Keith, and again with my best buddies Stefan and Walter the following Saturday. It was far from unheard-of for me to see a movie more than once, but this one really seized my imagination – and my ear. I’m betting I dragged Stefan and Walter.

On the imaginative front, as I recorded in my journal, I responded to Michelangelo Antonioni’s movie because it was Continental in sensibility, there was gorgeous photography, I liked the surrealism, and, oh yes, there was this bit about the “sexual candor,” as I labeled it. As I’ve already mentioned, I’d seen some on-screen nudity the preceding year with Dear John, and now there was this: Vanessa Redgrave topless, and David Hemmings romping on purple paper with Jane Birkin and Gillian Hills, plus Sarah Miles making love. But if this movie was largely about sex, it sure wasn’t about intimacy. Call it the anti-Dear John in that department.

In what seemed like a panoramic view of the Swinging London of that era, it seemed that intimacy, accountability, reality itself, had all gone missing. The conversations were truncated and stripped of context, people only had sex with people they didn’t like, and the meaning of everything seemed to be constantly shifting. I don’t want to play faux naïf; I’d been seeing other films with that hard, disenchanted European perspective. But this seemed to nail it down.

In what seemed like a panoramic view of the Swinging London of that era, it seemed that intimacy, accountability, reality itself, had all gone missing. The conversations were truncated and stripped of context, people only had sex with people they didn’t like, and the meaning of everything seemed to be constantly shifting. I don’t want to play faux naïf; I’d been seeing other films with that hard, disenchanted European perspective. But this seemed to nail it down.

I was personally quite the optimist, and didn’t subscribe to that outlook myself, but I was braced by the exposure to it.

More important was the music. I walked home whistling the main title theme. I’d recently become a member of one of the record clubs that were popular then – I think the Columbia Record Club. This was one of my selections. I must have listened to that yellow-covered LP dozens of times. I still have it today.

The big draw, of course, was the main title and the rest of the source music and score by Herbie Hancock. Unbeknownst to me, Hancock was providing me a brief (far too brief) glimpse of the main current of jazz at that moment: modal jazz. If you listen to that main title, at least as rendered on the LP,[1] you’ll hear that about half of that brief minute-and-a-half is taken up with powerful rhythm guitar and then blasting trumpets doing complicated things that resonate with the G-major 7th and G-minor 7th chords Herbie Hancock is laying down on the piano.[2] This willingness to work away at single chords for extended musical passages, along with not worrying much about orienting entire pieces toward single keys, is the hallmark of modal jazz. I heartily recommend the discussion of the crystallization of the modal jazz phenomenon in Ashley Kahn’s book, Kind of Blue (2000).[3]

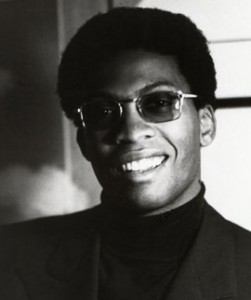

While Hancock (shown here as he looked in 1967) and his sidemen serve up a wide variety of jazz in a brief compass on the album, including some very accessible sort of lounge-y stuff, the main title and its companion, what’s called the closing title,[4] are harder-edged, and clearly black. I don’t think a white-led group could have given us that sound in 1966, when the score was recorded. (Of the seven musicians that I think I can hear on that cut, only one was white.)[5] Though racial generalizations are always dangerous, I think it’s safe to say that black and white jazz musicians of that era were largely involved with separate projects. Bop and modal jazz were deliberately off-putting to an ear trained to expect Western melody, and they made great technical demands on the players. Many of the players and composers were self-consciously pursuing a kind of racial authenticity.[6] This was, after all, the beginning of the era of Black Power as slogan and ideal. And a sort of hard, somewhat inaccessible, and technically dazzling musicianship was the stylistic weapon of choice.

While Hancock (shown here as he looked in 1967) and his sidemen serve up a wide variety of jazz in a brief compass on the album, including some very accessible sort of lounge-y stuff, the main title and its companion, what’s called the closing title,[4] are harder-edged, and clearly black. I don’t think a white-led group could have given us that sound in 1966, when the score was recorded. (Of the seven musicians that I think I can hear on that cut, only one was white.)[5] Though racial generalizations are always dangerous, I think it’s safe to say that black and white jazz musicians of that era were largely involved with separate projects. Bop and modal jazz were deliberately off-putting to an ear trained to expect Western melody, and they made great technical demands on the players. Many of the players and composers were self-consciously pursuing a kind of racial authenticity.[6] This was, after all, the beginning of the era of Black Power as slogan and ideal. And a sort of hard, somewhat inaccessible, and technically dazzling musicianship was the stylistic weapon of choice.

Later on, I could have illustrated that point with examples. For instance both Freddie Hubbard (whom you hear in that title music) and Maynard Ferguson were great trumpeters, but you’d never mistake the one for the other, and part of what made their sound distinct was that Hubbard was black and Ferguson white. Ditto pianists Herbie Hancock and Dave Brubeck. I didn’t know enough then to make such comparisons.

Later on, I also asked myself why Antonioni put Hancock’s music in Blow-Up. How is that music properly the theme for this movie? Reflect, there is no jazz club pictured that I could discern (even though Ronnie Scott’s, for instance, already enjoyed worldwide fame),[7] no jazz musicians (indeed, the only musicians pictured are the proto-punkish rockers, the Yardbirds). In fact, there are hardly any African or African American faces to be seen (two black nuns in the early going stand out, but nuns don’t bring jazz to mind). If this was supposed to be the theme music of this story, what was the commonality? I’ve never come to a convincing answer. Some of Hancock’s score makes it into the story as source music, which tells us that Thomas, the antihero, is a Hancock fan. And, as is mentioned in the first endnote, it appears the Hancock score that made it into the movie was actually recorded in New York.

The best I can come up with is that the world of Blow-Up was hip and modern, and so was the sound of Herbie Hancock, and perhaps Antonioni thought as well he could create the same kind of splash with an African American jazz score as Louis Malle had done in 1958 with Miles Davis’ contribution to Elevator to the Gallows, which snagged a Grammy nomination.

Whatever prompted Antonioni to invite Hancock into the movie, I was blown away by what Hancock did there. Because I didn’t know what I was hearing, I didn’t know how to look for more of it then (more about this in later entries). I had no one to teach me about it, and the rock was blaring so loudly in my ear (it was 1967, after all) that it’s no wonder I laid down that thread and didn’t pick it up properly again for some years.

Most of my Theme Songs stand out as reminders of something else. But my moment with the Blow-Up music was important for itself.

Nothing much came of it right then. But a marker had been laid down. Notice had been served that something remarkable was happening in the vast world of jazz, something I would need to get to know, someday.

[1] Renting the 2004 Turner/MGM DVD to bring myself back up to speed to write this entry, I discovered to my surprise that pretty much all of the music on the LP is either differently mixed from the way it is mixed in the movie, or perhaps comes from alternative takes. It emerges that the DVD is a butcher job which, among other things, supposedly leaves out the entire first scene (which I barely remember), and a lot of the crucial scene in which the murder is discovered (which I remember better). I say supposedly as to that first scene, because I recently found my old copy of the published edition of the script (1971), and I have to report that that scene isn’t in the script as published. Meaning either that it had already been cut by 1971 and not by Turner/MGM, or that memory is playing tricks on me, and on the person who wrote the just-hyperlinked comment. (And for another thing, I could have sworn I remember seeing Vanessa Redgrave completely topless; funny how such things stick in the mind.) Meanwhile, there were apparently two competing recording sessions; reportedly, Herbie Hancock did not like the product of a London session, and so redid the score with a group of musicians in New York. Given both the unreliability of the DVD and the fact that the score was recorded twice, I cannot be certain whether differences between its sound and that of the soundtrack album are owing to the album using material from outside the movie, or Turner/MGM taking liberties with the sound of the movie (perhaps using the London takes instead of the New York ones?). Neither would surprise me. I can only discuss the place of the album in my life and the development of my musical ear.

[2] I oversimplify when characterizing the chords, I’m sure. Hancock is a master of chords that you can’t quite tell what they are.

[3] Check out Pages 66-75 especially.

[4] Not heard on the above-mentioned DVD.

[5] I think I can hear Ron Carter on bass, Hancock on the piano, Jimmy Smith on organ, Jack De Johnette on drums, Freddie Hubbard and Joe Newman on trumpets, and Jim Hall on guitar.

[6] It led Hancock himself, for a little while, to an absurd place. His funk albums of the 70s are, in my opinion (and I know there are those who differ), a big embarrassment. I’m convinced that part of what motivated him (in addition to the wish to make some money doing what was hot) was a desire to do the black thing.

[7] The Yardbirds are playing in what apparently was a recreated Ricky-Tick club, where some American jazz was reportedly to be heard. However Ricky-Tick was devoted to all sorts of music like the rock music on display in the scene, and the Yardbirds were Brits.

Photo Sources: Movie image: http://i577.photobucket.com/albums/ss218/Jedimoonshyne9/BlowupLarge2.jpg . Hancock image: http://www.herbiehancock.com/#media.php .

Copyright (c) Jack L. B. Gohn, except for commercial images

Theme Songs Page | Previous Theme Song | Next Theme Song