The Case of the Missing Monuments, or None Dare Call It Treason

Recently my travels took me through several Southern states on US Route 1, which runs up the Eastern seaboard from Key West. As with most of the highways that had been locally named “trails” but changed to the standard US numbering system around 1926, pre-existing names also continue to be attached to parts of US-1, and incorporated into the signage. For example, sometimes US-1 is the Dixie Highway, sometimes the Federal Highway. Nothing wrong with that. But I found myself taking exception when I discovered that long stretches of it are named the Jefferson Davis Highway. Now, there is much federal money invested in this road,[1] some of which I saw used in construction projects I passed. And Davis is not being commemorated for his service to the federal government (in the U.S. Congress or in the Franklin Pierce administration): he is remembered primarily for having been the president of the Confederacy.

And the last time I checked, the Confederates were rebels against and traitors to the federal government. (Levying war against the United States is treason, under Art. III, § 3 of the Constitution.) Davis himself was actually charged with treason after he was captured in 1865, though President Andrew Johnson, exiting his office, granted Davis a pardon, so that Johnson’s successor Ulysses Grant could not prosecute him. But what does it mean that the man is honored at all?

My bemusement grew as I visited the state capitals of South and North Carolina and Virginia, all of which also lie astride US-1. The overwhelming impression one would get, from touring the capitol grounds in the Carolinas and looking at the monumentation, is that: a) the Civil War was a glorious affair, whose causes for some reason no one remembers; b) the South seems to have won the Civil War, though the details are vague; c) there never was such a thing as slavery; d) there was never a significant African American or Native American population in these states; and e) very little happened after the Civil War except for other wars, to which the gallant South sent (white) heroes.

There is one monument among the 27 surrounding the Columbia, SC capitol that explicitly acknowledges African Americans. The place of honor in front of the capitol, to be sure, is given over to a Confederate soldier on a pillar, close to a flagpole from which the Stars and Bars flutter. (It took a well-publicized fight in 2000 to remove them from the capitol dome.) But halfway between there and the Strom Thurmond memorial, you can see the African American History Monument. It was placed there in 2001 only after a colossal political struggle. And its promoters were not permitted to acknowledge any specific person, though there have been many nationally-prominent African Americans to emerge from the Palmetto State, including Dizzy Gillespie and Mary McLeod Bethune. Out of the 12 monuments on the grounds there that depict the human form, this monument is the only one with non-white faces. (And I’m not even counting the Jefferson Davis and Robert E. Lee highway monuments.)

In North Carolina the exclusion is even more profound. On the grounds are 14 monuments. Score: Whites 14, Others 0. Confederate figures depicted: 4.

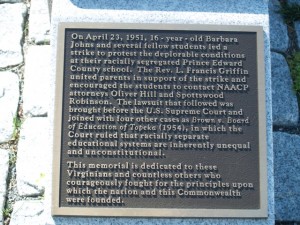

Virginia came late (2008) to the notion that African American history deserved mention in the monumentation around a state capitol. But when they did it, they did it much better. For one thing, there are only six monuments altogether. The Civil Rights Memorial is thus far more prominent. And the Memorial is focused on a particular event, the Virginia lawsuit that, together with cases from four other states, became Brown v. Board of Education, and on certain individuals, including the two lawyers who brought the suit, Oliver Hill and Spottiswood Robinson. (It’s always gratifying to see monuments commemorating lawyers.) The positioning is a bit weird, two monuments down from Stonewall Jackson. But the monument at least acknowledges the existence of a deep problem in Virginia’s history, and some of the efforts to address it. And though it is the object of some competition from the one true Civil War monument, the aforementioned Jackson, it is not drowned out by Confederate and Jim Crow nostalgia, as is the African American History Monument in South Carolina. And just the fact that it exists distinguishes Virginia from North Carolina.

That said, large stretches of “Jefferson Davis” Highway are superimposed on US-1 in Virginia. So the Old Dominion State is hardly free of inappropriate Confederate commemoration.

History, we are told, is written by the victors; apparently there’s an exception for the South, where the commemorated history barely includes the victory, and consistently omits slavery, the casus belli. This peculiar history written by the vanquished apparently extends to the law. In this Cloud Cuckoo Land of Confederate commemoration, it does not seem to matter that the CSA came about through treason, secession being illegal, and existed primarily and fundamentally to perpetuate one of the worst human rights abuses in history. (There were 4 million slaves in the South at the outset of the Civil War.) The federal government poured out lives and treasure to establish that secession was illegal, and that slavery must be abolished.

It is all very well to strive for reconciliation, but there is no justification for pretending that the sides were morally or legally equivalent. Even the truism that one man’s rebel is another man’s freedom fighter applies, if at all, only at the outset of a conflict. If the dispute has been settled against the insurgents by war, the pejorative label of rebel becomes more objectively certain, and arguments to the contrary more frivolous. As Ulysses Grant wrote of the purported legitimacy of secession: “The right of a state to secede from the Union [has been] settled forever by the highest tribunal – arms – that man can resort to.”[2]

And that truth explains the fundamental perversity of the inscription on yet another statue, this in the middle of the campus at Chapel Hill: “To the sons of the University

who entered the War of 1861-65 in answer to the call of their country … ”

With all due respect, it wasn’t a country. It tried to be one, but failed. And it tried to be one first and foremost in order to preserve slavery, a system that should have evoked nothing but shame in its defenders. Those “sons of the University” gave their devotion and their lives for worse than nothing. Their cause was so unworthy, their valor ought to forfeit any claim to commemoration, in statutes, on highway signs, or anywhere else. Especially while all the offsetting monuments – to the slaves, to the Underground Railway, to those who fought Jim Crow, to prominent descendants of slaves – are mysteriously missing.

A hundred and fifty years after the fact, we have apparently not learned that lesson.

[1]. Typical federal funding for highways in one year alone can be seen in http://www.fhwa.dot.gov/ohim/hwytaxes/2008/f106.cfm .

[2]. Quoted in http://jimostrowski.com/articles/secession.html , Note 93, citing D. Tipton, Nullification and Interposition in American Political Thought (University of New Mexico Press, 1969) at 50. (Citation to Ostrowski should not imply agreement with his arguments.)

Copyright © Jack L. B. Gohn