Old Hat But Interesting: Shepard’s HEARTLESS at Shepherdstown’s CATF

Theater Reviews Page | Previous Theater Review | Next Theater Review

Old Hat But Interesting: Shepard’s HEARTLESS at Shepherdstown’s CATF

Posted on BroadwayWorld.com July 16, 2013

[Note: The Contemporary American Theater Festival each year produces five new American plays in Shepherdstown, WV (an hour and a half from Baltimore) Wednesdays through Sundays throughout July. This is a review of one of this year’s productions. Each will be separately reviewed in this space.]

I am not sure what Shepard is doing in Shepherdstown. The Contemporary American Theater Festival held there is dedicated to performing “new American plays.” There’s nothing new to me about Sam Shepard‘s play Heartless; it seems distinctly old hat. I went back to a review I wrote of one of his plays for my college newspaper in 1970, and a number of the things I wrote about that play (The Holy Ghostly) could be said about Heartless. I commented how characters migrate into each other, how they become composites of various characters, how there is no predictable logic to their interactions, and how the drama loses the sense of being story-telling about distinct persons. I compared what Shepard did to abstract painting. And, on the evidence of Heartless, it’s still true.

An author who is still writing essentially the same play in 2013 that he wrote in 1970 is not contemporary, as I use the term. Shepard is probably one of the two greatest surviving masters (Edward Albee being the other) of the Theater of the Absurd, but that was essentially a 20th, not 21st-Century phenomenon. Shepard’s peers include Beckett, Ionesco, Pirandello, and Pinter. Not bad company to be in, but their movement is about played out, and for cause. Theater is much better at telling stories about characters with fixed identities and recognizable personalities than at enacting rituals whose meaning, logic and grammar are obscure. “The fundamental things apply,” as we learned from Casablanca, and Absurdism was a rebellion against the fundamental things. It did not take over, did not replace what it rebelled against. It was contemporary once, but no more.

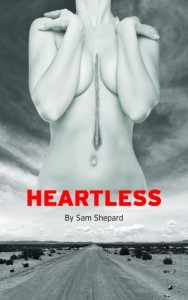

That said, if you don’t mind going back and witnessing DR. Shepard performing the same experiment again, you will see a handsome production. (So far as I can tell from attending two seasons of Shepherdstown, they don’t do unhandsome ones.) This one concerns Roscoe (Michael Cullen), a “not young anymore” professor, separated from his wife and adrift in a house full of women in the hills looking down on Los Angeles. The women are an invalided mother, Mable (Kathleen Butler), and two daughters Lucy (Cassie Beck) and Sally, plus Liz (Susannah Hoffman), who appears to be Mable’s nurse. But wait! Sally, we know from a spectacular moment in Act One when she turns to the audience with a big zipper scar from chest to navel, is using the heart of a person who died when she was little – except that Liz (we learn in Act Two) has the same scar and appears to have been the donor. But that would mean that …?? Well, while we’re puzzling through that, consider that Mable has given Roscoe (and the audience) two completely incompatible versions of Liz’s biography while Liz kept an inscrutable silence. Liz spends much of the first act polishing her hands and much of the second polishing her feet. Meanwhile big sister Lucy seems to have swapped places and personalities, and even clothes with Sally by the end. And all of this delivered with aplomb by a Sam Shepard who does not show his hand about how any of it works or what any of it means.

The reader may have twigged that I did not mention the actress who played Sally, and that is because I cannot predict who would be holding down the role when the reader might see the play. We in the media were told that before the final preview performance the actress who was to have played the part because suddenly unavailable for the moment, though she was expected to return. Rushed in to fill the part at least temporarily was Margot White, who had had one day of rehearsal and one performance before I saw her do the show. She was still, understandably, using a script for parts of Act Two. She seemed to fit the role perfectly. If I hadn’t been told about the substitution and seen one page of the script in her hand, I would never have known. Any theatrical troupe would be fortunate to recruit a ringer like White.

The juiciest part in the play, however, belongs to Butler. Casts at Shepherdstown tend to skew young, and Butler may have had an unfair advantage because she was the only actress of a certain age in any of the casts this year. There are things a mature performer can do, can get away with, that more youthful ones can’t, and Butler gives a little workshop on those things. Sitting in a wheelchair with immobile hands, with little but her voice and face as tools, Butler dominates every scene Shepard gives her. Of course, she’s meant to; Mable is fiercely, even abusively critical of everyone around her. Here, for instance, she first meets Roscoe in Sally’s company:

MABLE: (to ROSCOE) Who’re you?

ROSCOE: Uh-

SALLY: This is my friend-Roscoe.

MABLE: Let him speak for himself. He can speak for himself-(to ROSCOE) Can’t you?

ROSCOE: Yes, ma’am.

MABLE: Well then?

ROSCOE: I’m-

MABLE: What kind of ‘friend’ do you call yourself, Roscoe? A ‘friend/friend’; a ‘casual friend’ or a ‘friend to the death’. Are you any of those?

One soon recognizes that this Pinteresque bullying is all an act, a voice, an attitude, not the speech of a character conventionally realized. Still, an actress with a certain presence can make much of it. And Butler does.

I also liked, though I did not understand nor was meant to, Susannah Hoffman‘s performance as Liz. Shepard was aiming for a David Lynch-y weirdness with her character, an undead woman in an old-fashioned white nurse’s uniform (today’s nurses wear scrubs, of course) polishing her extremities nonstop, who bursts into song about how she wants to live. Hoffman does a great job of being a refugee from Twin Peaks.

And it would be hard to fault Ed Herendeen’s direction, which seems to have captured Shepard’s conception.

In short, it was an interesting production of a limited but interesting play. I just don’t know why I was seeing it where I was seeing it.

Copyright (c) Jack L. B. Gohn except for graphic

Theater Reviews Page | Previous Theater Review | Next Theater Review